Before Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh (CMP) reopened to the public on June 28th, Barbara Tucker, Director of CMP’s Travel Program, talked with me about ways to reengage members and bring them back to the Oakland museums.

With knowledge about my research on the 125th Anniversary of the founding of the Carnegie Library, Barbara suggested a 90-minute outdoor walking tour around the exterior of the massive building. Starting from where the oldest portion of the building (Portal Entry) meets the newest (Museum of Art) to the front of the historic library entrance, past the Diplodocus carnegii statue, to Forbes Avenue and the entrances of the music hall, natural history museum, and fine arts museum guarded by the statues of the noble quartet.

The tour was advertised on the CMP website under the Travel Program link, https://carnegiemuseums.org/things-to-do/travel-with-us/ and https://carnegiemuseums.org/kollar/, and accurately described as an activity fully compliant with CDC protocols. Within a week, the tour received overwhelming signups, which were organized by date and number of participants by Travel Program assistant Isabel Romanowski. Three tour dates were set in August and several more in September. Special private tours for donors and others in the fall continue to be arranged.

Andrew Carnegie, Founder:

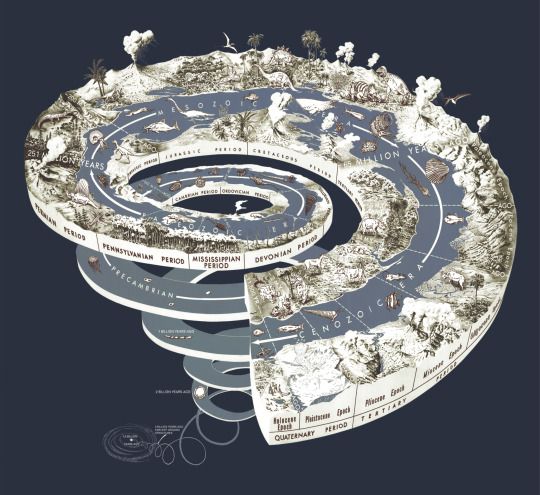

As guide for an exercise that involves close observation of architectural details, I face the challenge of getting participants to imagine this section of Pittsburgh long before any of the structures around in Oakland existed. The library and museums cover five acres of flat bottom land formed by the pre-Ice Age Monongahela River more than 1.2 million years ago. In far more recent times, the land was part of the Mary Schenley Mount Airy tract of 300 acres which was donated to the City of Pittsburgh in 1889 to create Schenley Park in her honor. Andrew Carnegie, (1835 – 1919) industrialist, steel magnate, and philanthropist, in 1895 saw the site as a place to build a complex with a library, fine arts gallery, science museum, and music hall that would represent the noble quartet of literature, art, science, and music.

The Library Tour Themes:

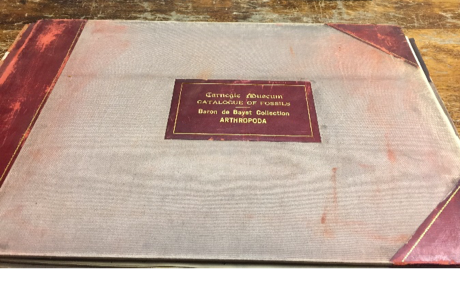

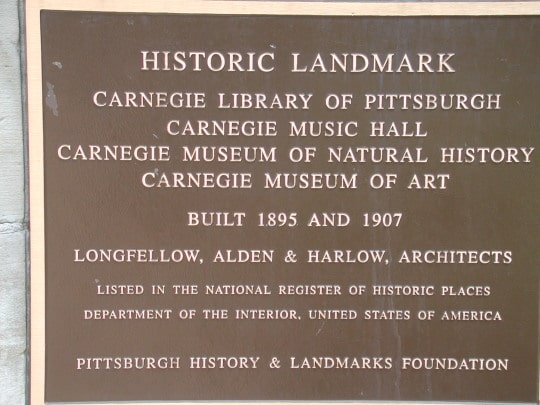

Tour groups assemble on the dark stone steps outside the Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA) rear entrance for an introduction focusing on the two connected, but architecturally different buildings: the Beaux-Arts style Carnegie Complex, with the original structure dating to1895, and later addition to 1907, which was built by Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow using Carnegie Steel (Fig. 2), and the modern Carnegie Museum of Art, built by architect Edward Larrabee Barnes in 1974.

Two rock types distinguish the building exteriors. The older portions of the building are clad in a light grey, easily carved, 370 million-year-old Berea Sandstone from Amherst, Ohio, while the exterior and much of the interior of Museum of Art is covered in the 295 million-year-old bluish iridescence Larvikite igneous rock from Larvik, Norway. When Barnes was commissioned to build CMOA, he chose the dark rock to blend with the older building’s coal dust veneer, a grime coating that was removed when the exterior stone was cleaned in 1990.

Landscape Art and Geology:

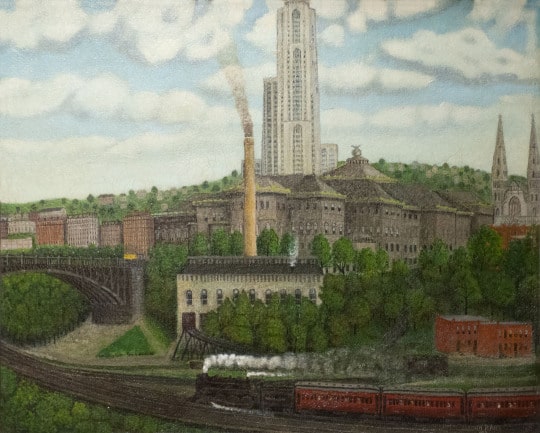

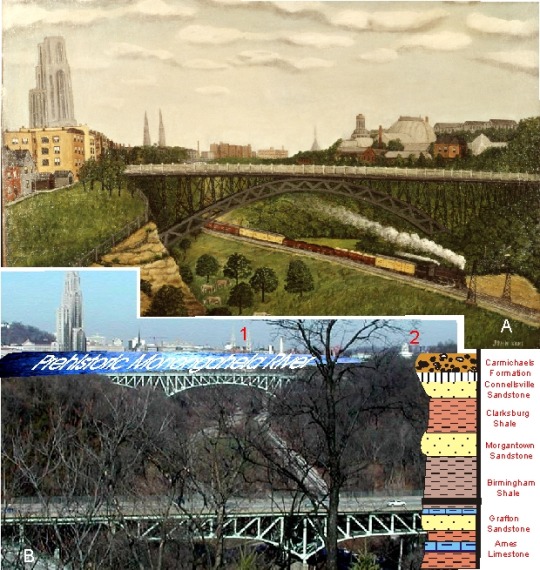

Pittsburgh’s landscape painter, John Kane’s (1860 – 1934), Cathedral of Learning, circa 1930 (Fig. 3), depicts the 150-foot-deep Junction Hollow with its operating railroad. The work also includes many important architectural references, the Schenley Park Bridge (1897), Carnegie Institute’s Bellefield Boiler Plant (designed by Alden and Harlow in 1907 to supply electricity and heat to adjacent buildings), the Carnegie Institute Extension (1907), and a then unfinished Cathedral of Learning. This painting is part of CMOA Fine Arts collections.

Another John Kane landscape, Panther Hollow, circa 1930 – 1934, (Fig. 4A) in combination with Cathedral of Learning has been used in teaching about the 300 million-year-old geology of Schenley Park (Fig. 4B2) and the pre-Pleistocene Monongahela River that formed the flat bottom landscape of Oakland, and through erosion, Junction Hollow (Fig. 4B1). Kollar and Brezinski 2010, Geology, Landscape, and John Kane’s Landscape Paintings.

Junction Hollow Landscape:

Kane’s Cathedral of Learning (1930) is an idealized green space of Junction Hollow, the Wilmot Street Bridge in the foreground (1907) now replaced with the Charles Anderson Bridge (1940), and Carnegie Tech’s (now Carnegie Mellon University’s) Hamerschlag Hall or Machinery Hall (1912), built by Henry Hornbostel, a Pittsburgh architect. Hornbostel designed a circular Roman temple wrapped about a tall yellow brick smokestack (Fig. 4A). The design is based on the Roman temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy, dating to the early 1st century BC. Hornbostel’s overall campus design focused on connection between art and science, with Junction Hollow representing the geological sciences. The architect Philip Johnston, who built Pittsburgh’s postmodern PPG Place (circa 1984), once contrasted the Bellefield Boiler Plant smokestack as “the ugliest in the world to Machinery Hall’s smokestack as the most beautiful.” In novelist Michael Chabon’s debut novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, (1988) the Bellefield Boiler Plant, termed “the cloud factory” by the narrator, is the setting for a pivotal scene.

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh (Main):

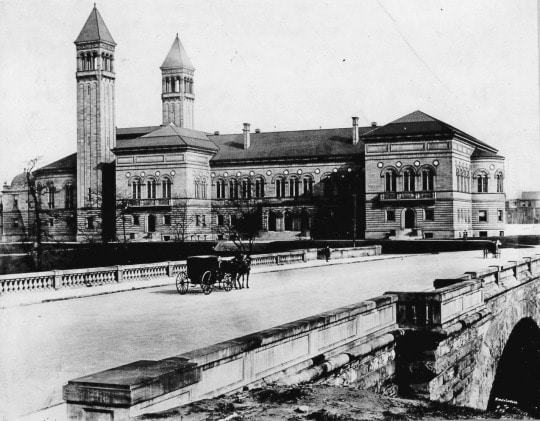

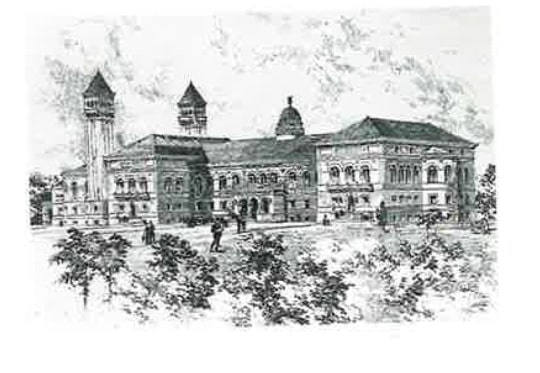

The separate institutions we now know as Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Carnegie Museum of Art can track their origins to exhibits and galleries within space now fully occupied by Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. An image of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in 1902 from the Bellefield Bridge, a structure now buried under the Mary Schenley Memorial Fountain (1918), reveals eclecticism in architectural features (Fig. 5). The west facing frontage doorways and portico of the library features, CARNEGIE LIBRARY, FREE TO THE PEOPLE, and 24 carved writer names. Missing from the names is Carnegie’s favorite poet, Robert Burns, whose statue was dedicated in 1914 on the grounds of Phipps Conservancy. Three separate entrances are served by granite steps of Permian age from Vermont, one for the science museum, one for the Department of Fine Arts, and the third, with distinctive Romanesque round doorways, brass doors with intricate features, and keystone scrolling, for the Library. This entrance was designed by Harlow, who was the draftsman on the McKim, Mead, and White team responsible for the Beaux-Arts Boston Public Library (1895). When the Carnegie Institute Extension was constructed in 1907, the science museum and fine arts museum collections were moved into the new space. The former spaces in the library became the Children’s Room, Pennsylvania Room, and Music Library.

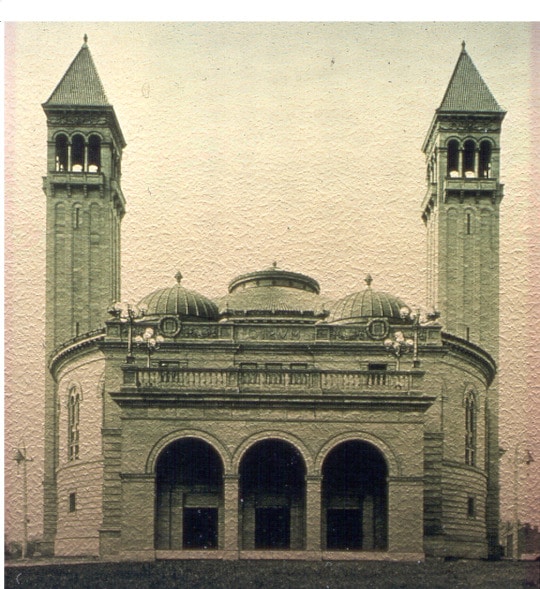

A challenge at this point in the tour involves discussing features that are not visible up close. The Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow’s Italian Renaissance and Beaux-Arts H-shaped parallelogram winning design featured a copula (Fig. 6) on top of the red tile roof that was never built. Eclecticism features include a double apse, a smaller shaped semi-circular extension of the library’s wall on the southside of the building, and larger apse on the north or Forbes Avenue side of the building, with the semicircular Music Hall auditorium, designed by Longfellow. The music hall exterior was structurally changed by the 1907 construction (Fig. 7).

The exterior Berea Sandstone reveals rustication masonry techniques with the cut blocks on the exterior first floor level distinguished by ashlar pillow horizontal border stone, and smooth masonry from the second floor to the cornice below the roof line. The second floor late Gothic style windows are divided by a vertical element called a mullion that helps with rigid support of the window arch and divides the window panels. Two symmetrical Campanile towers that Carnegie called “those donkey ears” were modeled after the San Marco Bell Tower in Venice, Italy. The towers served as an architectural offset to the semicircular exterior walls of the music auditorium and were removed in 1902 for the construction of the Carnegie Institute Extension. The installation of the towers can be interpreted as a tribute to Henry Hobson Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse twin towers (1888).

Architects choice of light grey sandstone and red tile roof:

The library’s red tile roof incorporated multiple glass roofs over the library, fine arts galleries, and science museum (all shaded from exterior sunlight today) which typified the Beau-Arts style. Keep in mind, the library did not have electric light. Light was provided by gas lighting and natural sunlight. Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow wrote that “the choice of a red tile roof and grey Ohio (Berea) Sandstone was intentional to contrast with Pittsburgh’s grey skies and the changing seasonal colors of the foliage in Schenley Park.”

The Beaux-Arts Architecture of the Carnegie Institute Extension 1907:

After Longfellow returned to his Boston practice in 1896, Alden and Harlow received the commission to build the Carnegie Institute Extension (1907) (Fig. 8). Their efforts created one of the great Beaux-Arts building in the United States. As Cynthia Field, Smithsonian Architecture Historian, stated in 1985, “the building itself is the greatest object of the entire museum collection.” Formal recognition of the building’s architectural importance exists in two historic landmark plagues placed outside of the Carnegie Library entrance and the Museums’ Carriage Drive entrance (Fig. 9).

New exterior features of the 1907 extension work included the replacement of the red tile roof with copper, the addition of an armillary sphere, the construction, with a colonnade of solid Corinthian fluted columns of Berea Sandstone, four portico porches over the main entrances to the library, music hall, natural history and art museum, and eastside of building (now removed), and the creation, along Forbes Avenue, of a main Carriage Drive entrance with direct access to the galleries. The carved names of authors, artists, musicians, and scientists in the buildings’ entablature, a Victorian era practice, extends around the building from the library’s southeast corner to the music hall entrance, and natural history and the fine arts entrances.

Also notable along Forbes Avenue are John Massey Rhind’s noble quartet statues that guard the Music Hall and Natural History and Art entrances. The four male figures all seated in classic Greek chairs are Michelangelo (art), Shakespeare (literature), Bach (music), and Galileo (science). Standing three stories above the quartet on the edge of the roof, four groups of female allegorical figures represent literature, music, art, and science as well. The bronze figures were casted in Naples, Italy in 1907 (Fig 8).

Inside the 1907 Architecture and Building Stones:

The architects created 13 new interior spaces where three grand spaces stand out for specific architecture styles such as, the Beaux-Arts Grand Staircase (voted in 2018 as the 8th best museum staircase in the world), the Neoclassical Hall of Sculpture, and neo-Baroque Music Hall Foyer. The extension used 32 varieties of marbles and fossil limestones, many from antiquity, quarried and imported from Algeria, Croatia, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, and the United States.

Since 2004, the collaboration between the CMP Travel Program and the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology has been highly successful reaching out to our members and patrons. This summer’s tours generated some particularly appreciative comments:

The Carnegie’s resident scientists are a defining characteristic of this noble institution. Might be an anachronism in an era when museums are focused on providing ‘destination’ entertainment and hosting special events for swells, but while treasures like Dr. Kollar are still on staff, it’s a splendid idea to facilitate interaction between them and museum visitors. Congratulations on a most enjoyable program. -Ron Sommer

Albert was very informative and interesting. I found it most valuable learning the history of the area. -Janet Seifert

I can’t stress enough how unusual and interesting it was to have a geologist give us the tour. It had never occurred to me before that there’s so much one can learn about building materials from a geologist. -Neepa Majumdar

Albert D. Kollar is Collection Manager and Carnegie’s Historian of the Carnegie’s Building Stones. Barbara Tucker is Director of Carnegie Travel Program.