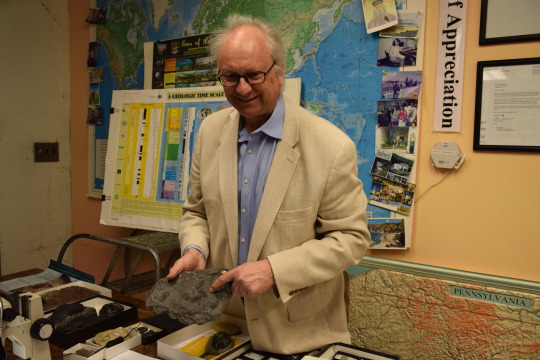

In August, Collection Manager Albert Kollar (Section of Invertebrate Paleontology) was notified by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists–one of the world’s largest geological professional societies–that he had been selected to receive the George V. Cohee Public Service Award. The award recognizes the contributions of geologists to the public. With Albert’s service in the Pittsburgh Geological Society and his long record of public education, field trips, and outreach devoted to the geosciences, this award is an appropriate tribute for his 40+ years of public service.