Afraid you missed our most recent Scientists Live with Mason Heberling in the Herbarium? You can tune in anytime here or on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Youtube channel. Binge watch the whole Scientists Live series in our Scientists Live playlist.

herbarium

Indiana, Pennsylvania: Christmas Tree Capital of the World

Did you know that Pennsylvania is one of the top states for Christmas tree farms? In fact, southwestern Pennsylvania’s very own Indiana County is known as the “Christmas Tree Capital of the World.” According to the Indiana County Christmas Tree Growers’ Association, the title arose in 1956, when an estimated 700,000 trees were cut that year in the county.

Believe it or not, there are no Carnegie Museum specimens from Indiana County collected in the month of December. This is not all that surprising, as most specimens aren’t collected in the winter.

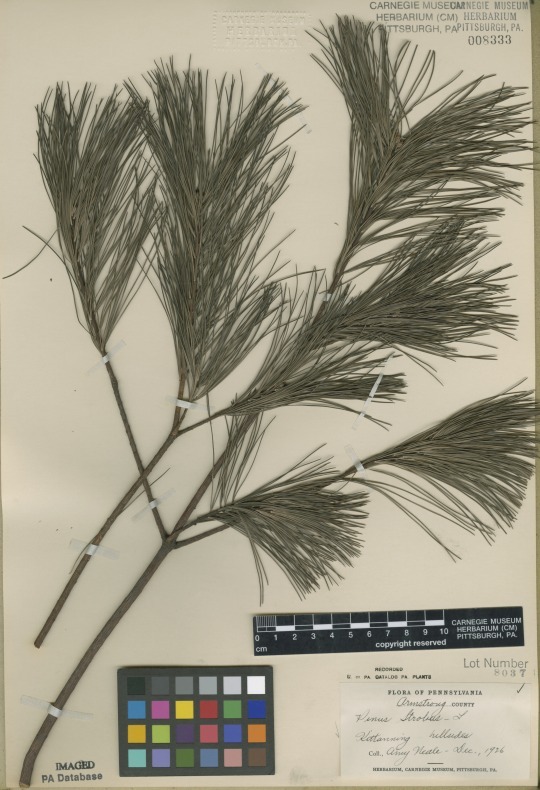

These Pennsylvania specimens shown above were collected sometime in December (exact day unknown): White Pine (Pinus strobus) in Kittanning in 1926 and Scots Pine (or “Scotch Pine”; Pinus sylvestris) from cultivation in

Avalon in 1902. Both species are cultivated and used as decorative trees for the holidays, but less commonly than in the past. Many different evergreen conifer species are cultivated in the United States for decorative use during

the holidays. Needle length, softness, retention, color, and even scent vary by species or variety. Similarly, branching characteristics and branch strength differs by species. Plus, some species grow faster and easier than

others, which means some species are cheaper.

Before farms began cultivating trees for that purpose in the early 20th century, people just went to the woods to cut down their tree for the holidays. Some of the first Christmas tree farms in the United States started in Indiana County as early as 1918. Many farms in the region turned their fields into Christmas tree farms as it became profitable. By 1960, more than 1 million trees were harvested per year in Indiana County alone. The harvest in Pennsylvania has declined for several reasons, including increased popularity of artificial trees and consumer interest in Frasier fir trees (Abies fraseri; which are native to the southern Appalachians and grows slower in Pennsylvania than farms in North Carolina). However, Pennsylvania is still among the top five states in terms of both number of working Christmas tree farms and trees harvested. According to the National Christmas Tree Association, 31,577 acres in Pennsylvania are used as Christmas tree plantations. Many of the Christmas tree lots in southwestern Pennsylvania get their trees from farms in Indiana County.

Botanists at Carnegie Museum of Natural History share pieces of the herbarium’s historical hidden collection on the dates they were discovered or collected. Check back for more!

Collected on this Day in 1928

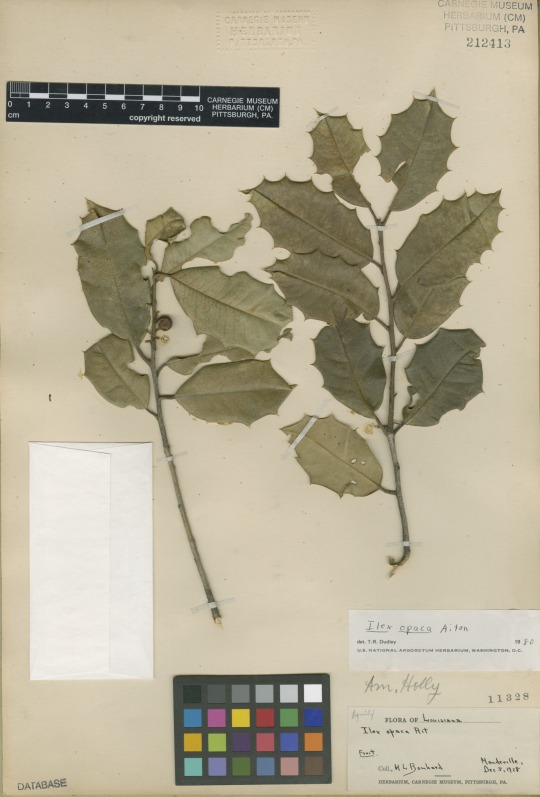

Are you decking your halls with boughs of holly? This specimen of American holly (Ilex opaca) was collected by M.L. Bomhard in Mandeville, Louisiana on December 8, 1928. The holly revered for its holiday cheer usually refers to a related European species, Ilex aquifolium, but there are native holly species in North America that are equally, if not more, cheerful.

Like most other hollies, American holly is dioecious, meaning it has male and female flowers on separate plants. Only the female plants have the characteristic bright red berries we all know and love. American holly stands out as one of the few broadleaved evergreen trees native to the Eastern US (i.e., has green leaves during winter that are not needles). This species is near the northern edge of its range in Pennsylvania and is more common in southern states. It is listed in Pennsylvania as a species of “special concern” due to its relative rarity.

Botanists at Carnegie Museum of Natural History share pieces of the herbarium’s historical hidden collection on the dates they were discovered or collected. Check back for more!

Collected on this Day in 1896

Collected on this Day in 1896

Collected on October 6, 1896 (the same year Carnegie Museum was founded), this specimen was found by early museum botanist John Shafer on Jack’s Island, a small island on the Allegheny River (between Harrison Township and city of Lower Burrell).

Despite the name, New England aster can be found across eastern North America. Along with many other species in the genus Aster, this species was recently reclassified in the Symphyotrichum genus. Symphyotrichum novae-angliae is a perennial (lives for several years) with beautiful deep blue-purple flowers. Like other plants in the sunflower family (Asteraceae), the flowers are actually a cluster of flowers (heads) composed of many flowers, with ray and/or disk flowers.

Photo caption: View of Jack’s Island from Braeburn (Lower Burrell), PA. New England aster might still be on the island, but note the dense stands of invasive giant knotweed that now lines the river and island. Introduced to the United States as a garden plant in 1894, Giant knotweed (Fallopia sachilinensis) was not yet in our area when this aster specimen was collected in 1896.

Collected on this Day in 1900

North America used to have over 150 species in the genus Aster. But now only one species remains. That isn’t because they went extinct, but instead, they were re-named. Many of these species are still referred to in general as “asters.”

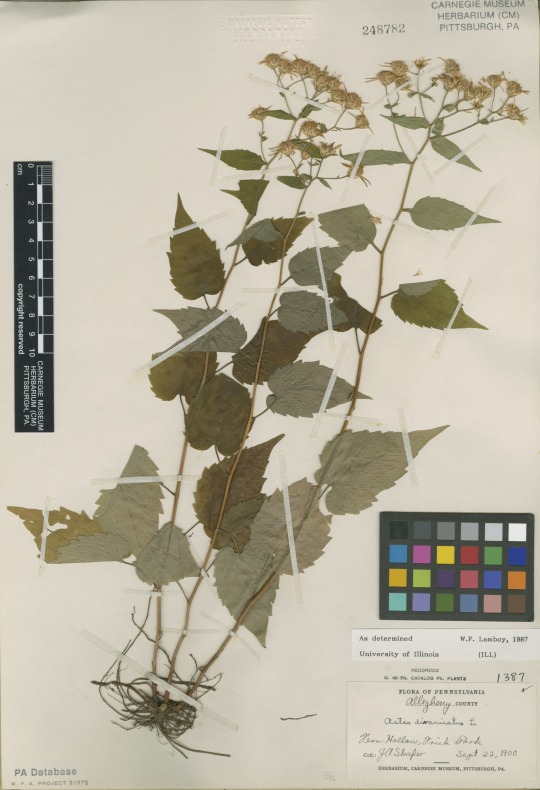

Collected on September 22, 1900, this specimen was found in Fern Hollow, Frick Park, Pittsburgh by early museum botanist John Shafer.

Eurybia divaricata (formerly Aster divaricatus) is commonly known as “white wood aster.” This beautiful fall blooming plant (like many asters) is a common native in eastern United States forests.

So why the new name? Taxonomy (the science of classifying organisms) is an ever-changing science, subject to revision as more research is done, especially at the molecular (DNA) level. As we understand how organisms are related, we can better understand the history of life on Earth. Taxonomic studies of plants often lead to the splitting of one species into many or the lumping of many species into one. In some cases, a “new” rare species may have been hiding under our noses, previously grouped with another species. These studies are important for the conservation and protection of vulnerable species. We must know what these species are to actually protect them!

Like most herbaria (plural for herbarium), the Carnegie Museum herbarium is organized by genus within families. Earlier this year, collections manager Bonnie Isaac and a team of interns and volunteers reorganized the sunflower family (Asteraceae), one of the largest families of flowering plants. After a month of reorganizing and renaming folders, the work is still ongoing. No surprise, as this family is represented by over 51,000 specimens (or about 10% of the entire collection)! Ongoing taxonomic rearrangements like these are just one reason why the work of herbarium staff is never done.

Botanists at Carnegie Museum of Natural History share pieces of the herbarium’s historical hidden collection on the dates they were discovered or collected. Check back for more!

Collected on this Day in 2007

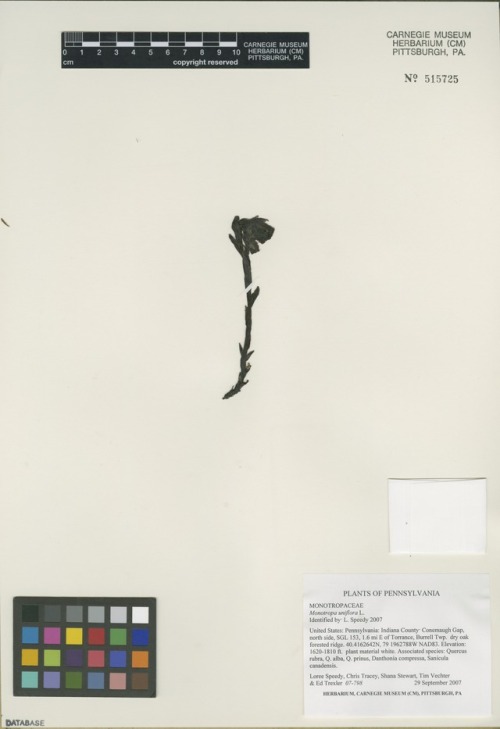

Not all plants in our area photosynthesize! Collected on September 29, 2007, this specimen was collected by Loree Speedy in dry woods in Burrell Township, Indiana County, PA (near Blairsville). Often mistaken for a fungus, Monotropa uniflora, commonly known as the ghost plant, is indeed a flowering plant in the blueberry family.

When alive, the plant is white (hence the name ghost plant), but turns black when dried. It lacks the green chlorophyll pigments of most plants, and therefore does not make its own sugars through photosynthesis. Instead, Monotropa uniflora is a heterotroph.

Like humans, heterotrophs ingest or absorb carbon necessary for life from organic sources, rather than fixing carbon from atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis). More specifically, this plant is a myco-heterotroph.

The way this plant gets its food is incredible. It parasitizes mycorrhizal fungi in the soil. And where does the mycorrhizal fungi get its food? These fungi form a close relationship (symbiosis) with many forest trees, shrubs and herbs, where the fungi aid the host plant in water and nutrient uptake and the fungi receive sugars from the plant in return. This complex relationship was shown using radioactive carbon dioxide, tracking tagged carbon molecules from a host tree to Monotropa uniflora.

So…ultimately, the food for this non-photosynthetic plant comes from other plants in the forest!

Botanists at Carnegie Museum of Natural History share pieces of the herbarium’s historical hidden collection on the dates they were discovered or collected. Check back for more!