Researchers from Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Michigan State University report plant specimens are being used in novel new ways that could influence future environmental policy, species conservation, and collections-based science. Specimen digitization and new data analysis technologies increase the relevance of herbaria for scientific research, education, and societal issues like climate change and invasive species. The study, titled “The Changing Uses of Herbarium Data in an Era of Global Change,” was published September 4, 2019 and is featured on the cover of the October issue of BioScience.

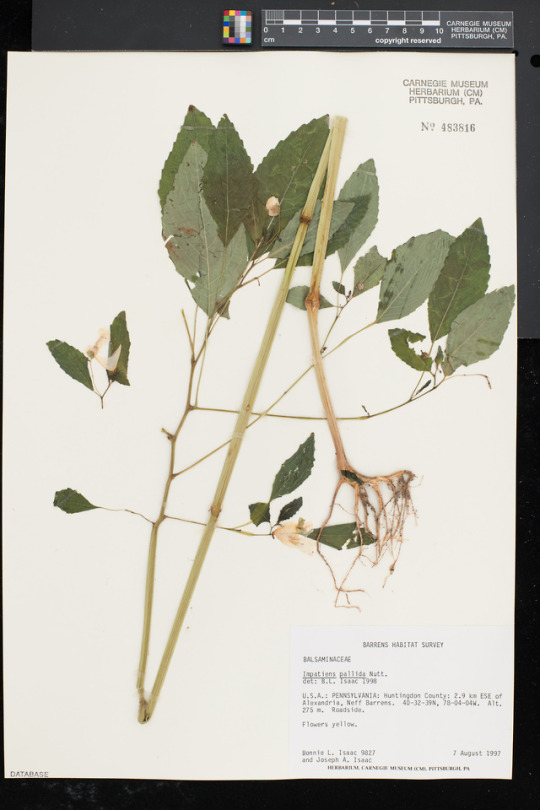

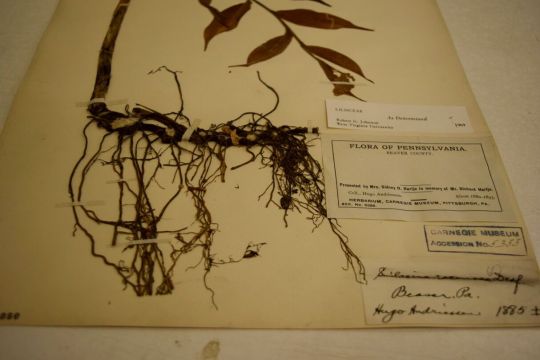

Nearly 390 million plant specimens are kept in over 3000 herbaria around the world, with more specimens collected each day. Plant collection is a centuries-old practice, and herbaria have long been critical resources for discovering and formally describing new species, a core function that continues today. However, collections use is expanding to provide clues about how global changes impact certain species.

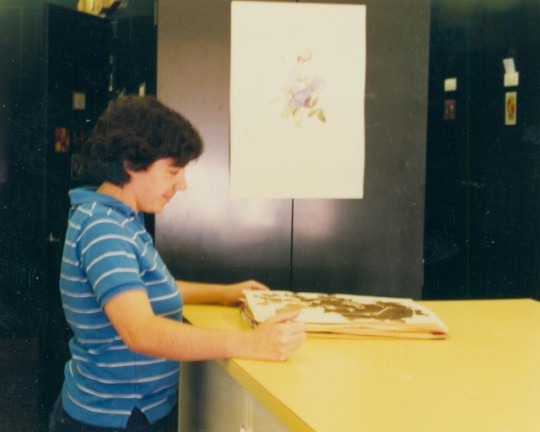

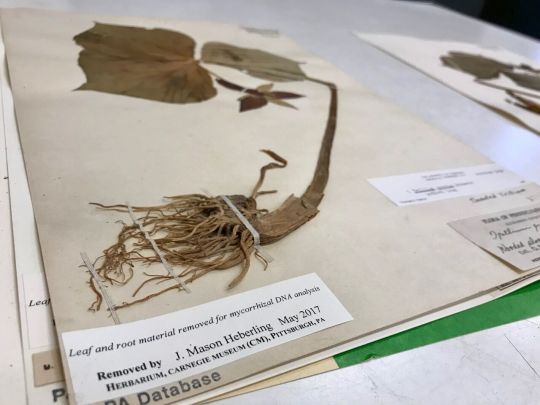

The new uses of herbarium specimens documented by Mason Heberling, Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Stephen Tonsor, Director of Science at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Alan Prather, Associate Professor of Plant Biology at Michigan State University, illustrate the increased value of specimens and herbaria in the Anthropocene, our current era. Changing use of specimens is part of a larger trend of change in the roles of natural history museums from repositories of knowledge to active leaders in scientific research that has a direct impact on life today.

“Museum specimens are being leveraged in innovative and powerful ways that most collectors and curators couldn’t even dream of a century, or even decades, ago,” says Heberling, “Natural history collections are perhaps more relevant than ever. These specimens have important stories to tell to understand the past, present, and future of life.”

The entire study is available online.

The Changing Uses of Herbarium Data in an Era of Global Change

Abstract: Widespread specimen digitization has greatly enhanced the use of herbarium data in scientific research. Publications using herbarium data have increased exponentially over the last century. Here, we review changing uses of herbaria through time with a computational text analysis of 13,702 articles from 1923 to 2017 that quantitatively complements traditional review approaches. Although maintaining its core contribution to taxonomic knowledge, herbarium use has diversified from a few dominant research topics a century ago (e.g., taxonomic notes, botanical history, local observations), with many topics only recently emerging (e.g., biodiversity informatics, global change biology, DNA analyses). Specimens are now appreciated as temporally and spatially extensive sources of genotypic, phenotypic, and biogeographic data. Specimens are increasingly used in ways that influence our ability to steward future biodiversity. As we enter the Anthropocene, herbaria have likewise entered a new era with enhanced scientific, educational, and societal relevance.