by Ian N. Roa

Museums are integral to our communities because they are institutions that provide public education and outreach to better understand the world we live in. Visitors often think of museums in terms of displays, animal taxidermy mounts in dioramas, or jars of preserved amphibians, for example, but much of the important work of museums occurs behind the scenes. I developed a clear understanding of this situation through two different interactions with the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

I am an archaeology graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt), and I met Stevie Kennedy-Gold, the Collection Manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles, in 2019 when her assistance helped me answer a research question. I specialize in zooarchaeology, that is the of study animals in archeological contexts, in the Maya lowlands of western Belize. Unfortunately, due to the wet, humid climate of the jungle, preservation of bone is not always the greatest. There exists, however, a necklace made of vertebrae that was found still clutched in the hand of an ancient Maya elite. Based upon several characteristics of each vertebra, I knew the necklace was made up of reptile but could not deduce anything more specific. When I reached out to Stevie, she helped me figure out that the necklace was made of bones from numerous snakes! The significance of finding out what kind of animal the necklace was made from helps us to understand the ways humans interacted with their environment, in this case animals who share the same landscape. Even more exciting is the cosmological importance of the serpent to the Maya culture where the creatures primarily symbolize rebirth and renewal.

This positive experience of having my doctoral research aided by a museum collection convinced me of how important it is to make sure such resources are well managed for generations to come. When I reached out to Stevie for a second time, it was to offer my time in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles for any project I could assist. When we got started, I was asked to help catalog the osteological inventory of reptiles and amphibians, which is fitting as Stevie has nicknamed me “the bone guy” for my specialty as a zooarchaeologist. The work involves locating each specimen, identifying which components of the skeleton are present, and noting any articulation or soft tissue (such as skin) that may be present. Any necessary steps for later upkeep to maintain preservation is also recorded, procedures such as cleaning skeletal pieces, removing dead dermestid beetles, and transferring specimens to new storage boxes. This experience has allowed me to further familiarize myself with diverse taxonomic groups and even inflammatory and autoimmune pathologies (Fig. 2)!

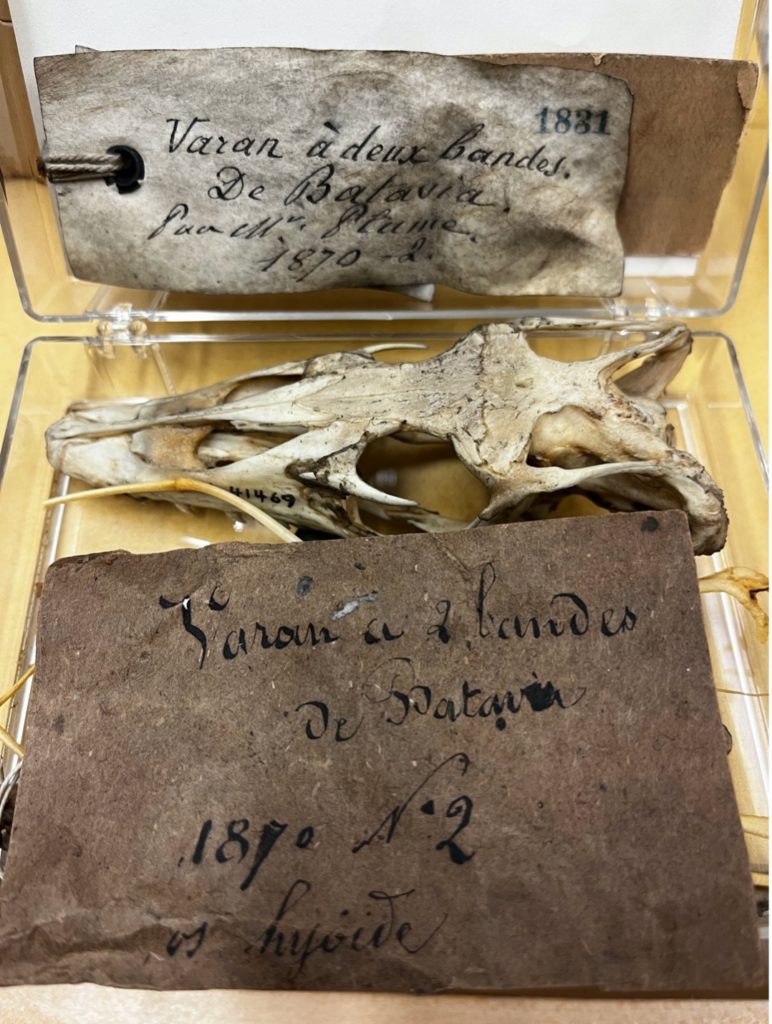

Though it is an arduous task to organize and record the entire osteological collection between Stevie, a couple of section work-studies, and myself, it is also a load of fun (or perhaps torturous levels of organization is my crazy idea of fun). No, really! As we go through each cabinet, drawer, and box we stumble across some really fantastic skeletons of lizards, snakes, crocodiles, turtles, and more (Fig. 3). One of my favorites was of an Asian water monitor (Varanus salvator), because it is the oldest specimen in the entire herpetology collection at CMNH, and even includes a beautiful hand-written record of this original skeleton.

Ian N. Roa is an archaeology graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh.

Related Content

A Head Above the Rest: Unearthing the Story of Our Leatherback Sea Turtle

Meet the Fossil Detectives in the Basement

Do Snakes Believe in the Tooth Fairy?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Roa, Ian N.Publication date: July 15, 2022