Carnegie Museum of Natural History has many type specimens in our collections. A type specimen is the name bearing specimen of a species. That means that that specimen was the first to be identified and named as a unique species. In Dinosaurs in Their Time there are 12 type specimens on display. Learn a little more about them below and the next time you visit see if you can find them all!

Redondosaurus bermani

Redondosaurus bermani lived during the Triassic period. While this animal looks like a large crocodile, it is a phytosaur, or an animal that closely resembles a crocodilian, though they are not closely related. The specimen here is a skull.

Dolabrosaurus aquatilis

Dolabrosaurus aquatilis lived during the Triassic period. It was a small reptile and specimens have been found in modern New Mexico. lived during the Triassic period. While this animal looks like a large crocodile, it is a phytosaur, or an animal that closely resembles a crocodilian, though they are not closely related. The specimen here is a skull.

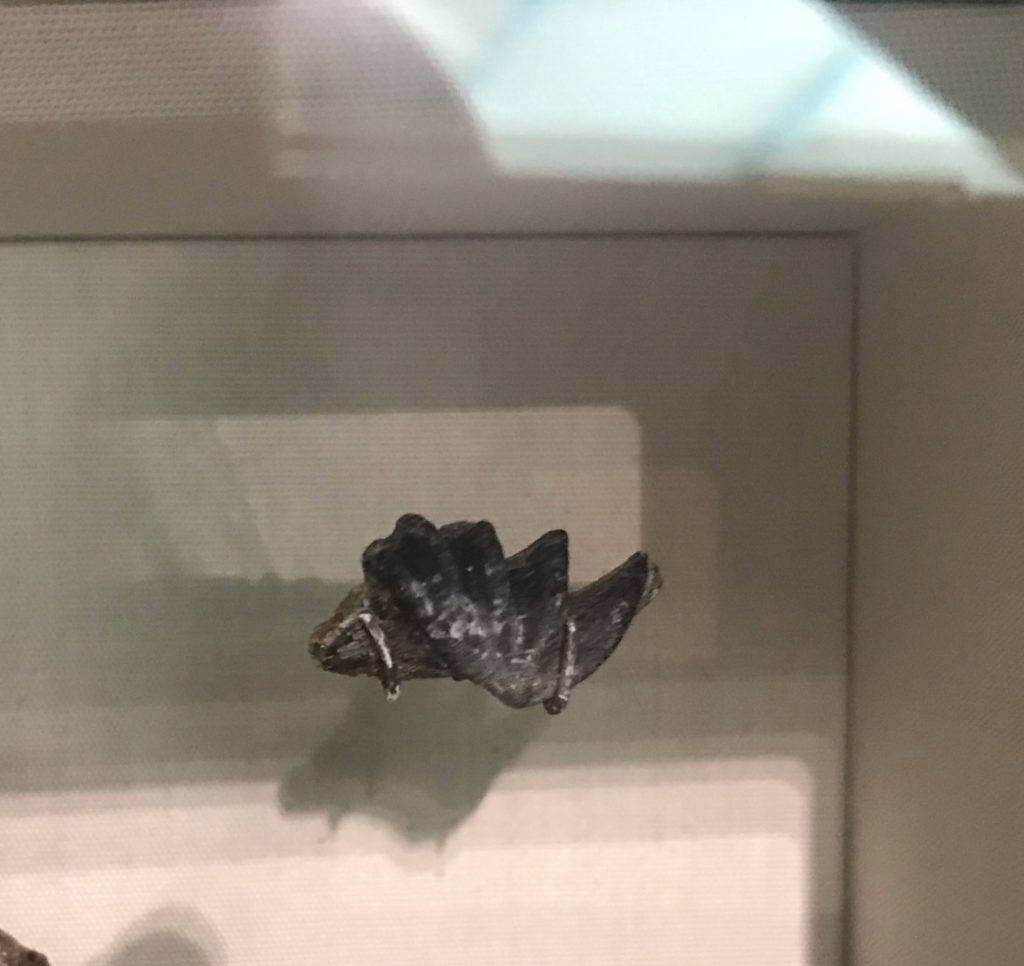

Ceradotus felchi

Ceradotus felchi was a lobe-finned lungfish that lived during the late Jurassic period. Though this species of lungfish is extinct, there are still several lungfish species that still exist today, including relatives of this species. The fossil on display is a tooth plate.

Hoplosuchus kayi

Hoplosuchus kayi is a tiny, heavily armored land crocodile that lived during the Jurassic period. This is the only definitive specimen of this species and it was discovered by a ten-year-old boy, Jesse York, in 1917.

Apatosaurus louisae

Apatosaurus louisae was a sauropod (long-necked) dinosaur that lived during the late Jurassic period. This species was once incorrectly called Brontosaurus. Only one Apatosaurus louisae skull has ever been found and it is in our collection, though the skull on display is a replica because the real skull is very delicate. Apatosaurus louisae got its name from Andrew Carnegie’s wife, Louisa.

Camptosaurus aphanoecetes

Camptosaurus aphanoecetes stood on display at the museum for over 60 years, embedded in the rock in which it was found and incorrectly identified as Camptosaurus dispar. When Dinosaurs in Their Time was renovated it was discovered that our Camptosaurus was a brand-new species!

Diplodocus carnegii

Diplodocus carnegii or Dippy, is our most famous dinosaur because numerous copies stand in museums around the world! This species lived in what is now the North American mid-west during the late Jurassic period. Dippy was discovered in 1899 and has been on display since 1907.

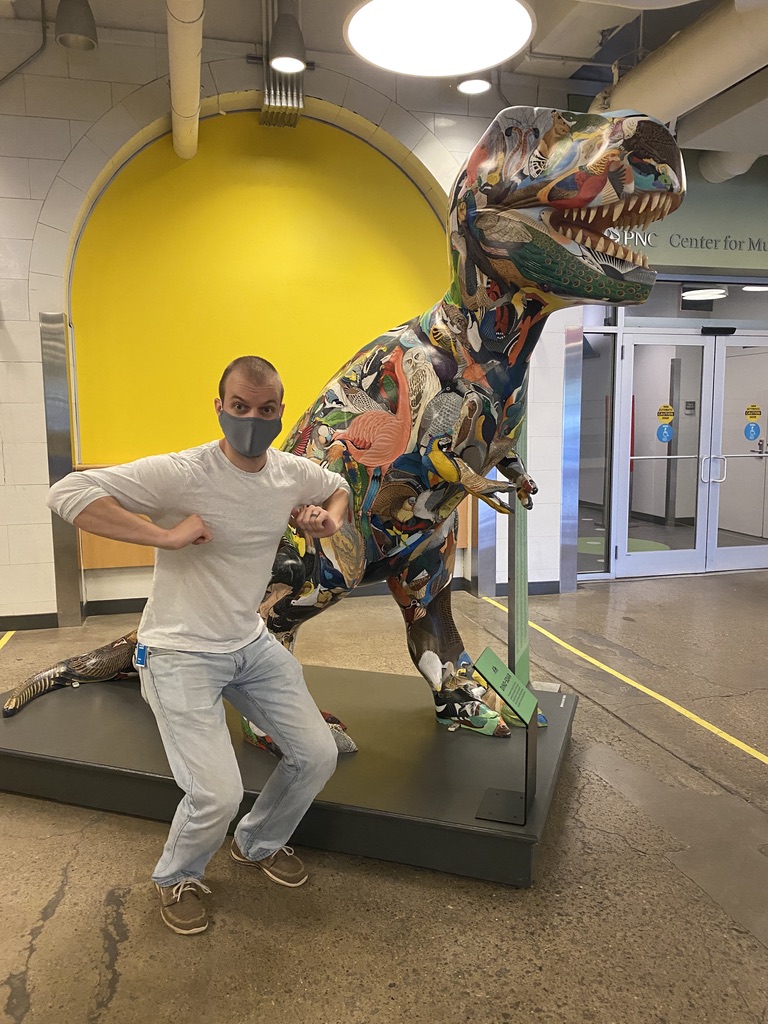

Tyrannosaurus rex

Tyrannosaurus rex is perhaps the best-known species of dinosaur. Our specimen was discovered by Barnum Brown, the assistant curator of the American Museum of Natural History in 1900. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History bought this specimen for $7,000 in 1941. T. rex lived during the Cretaceous period.

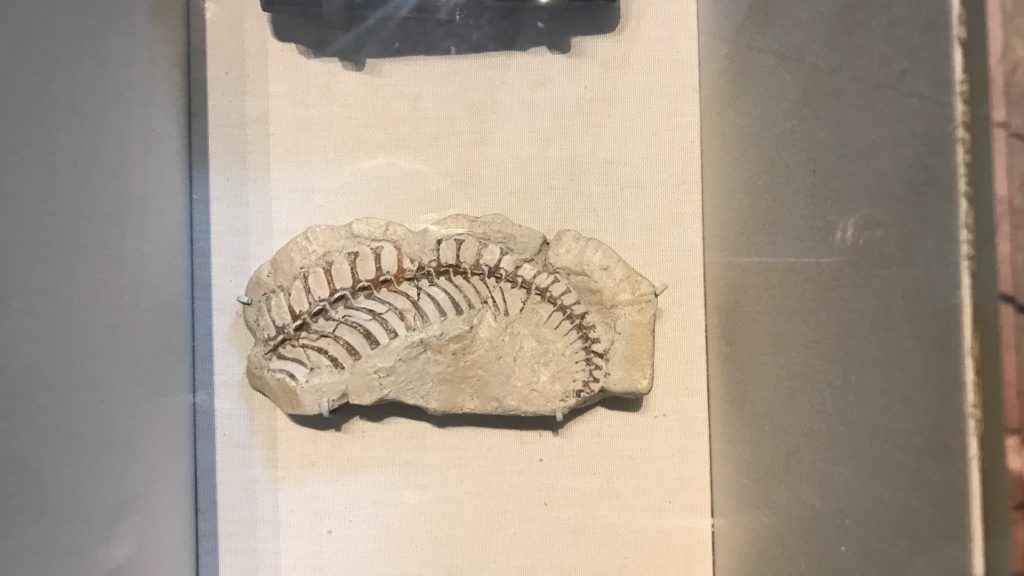

Opisthotriton kayi

Opisthotriton kayi was a large salamander that lived in what is now known as Montana during the Cretaceous period. The fossils shown here are skull fragments and vertebra (the bones that make up the spine). These are the only known fossils of this species.

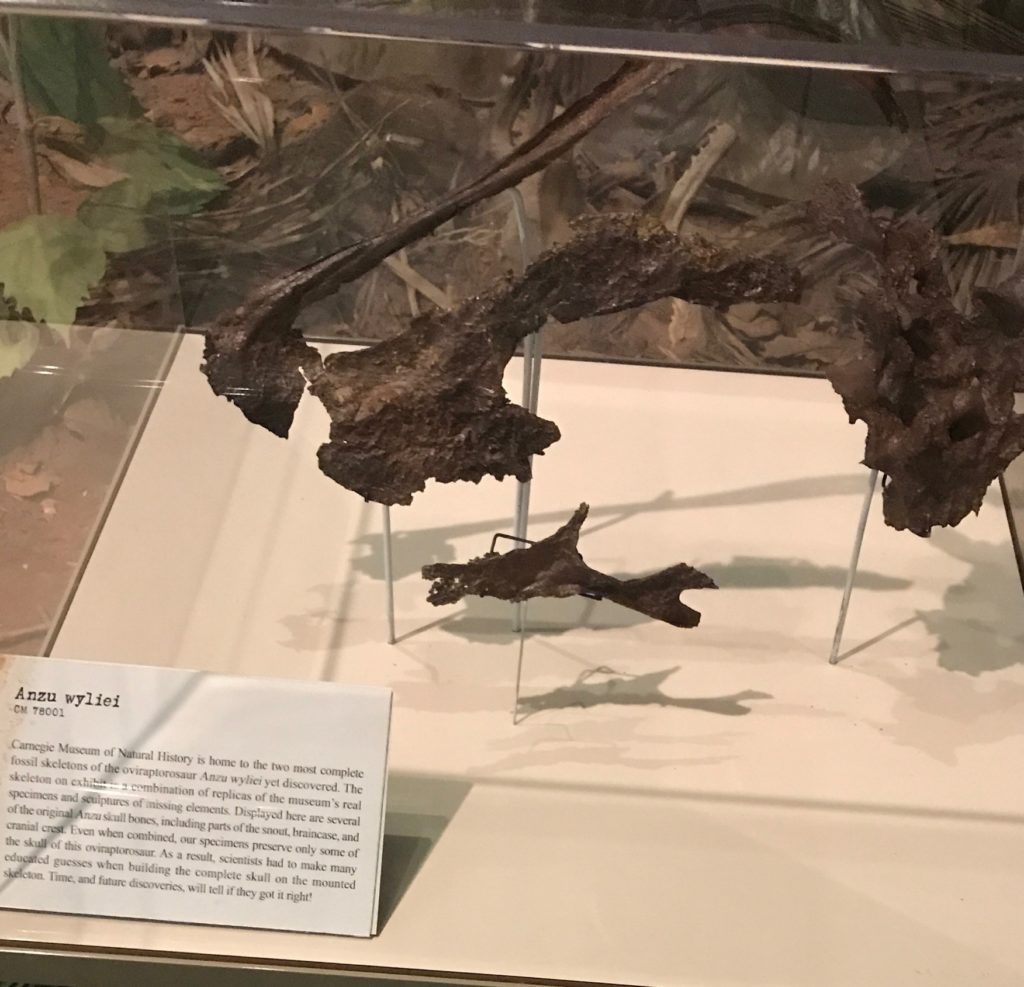

Anzu wyliei

Anzu wyliei was a large oviraptorosaur that lived during the Cretaceous period and discovered by our own paleontologist at the museum, Matt Lamanna! The fragments here are original pieces of the skull, but even if they were put together, they would not form a complete skull.

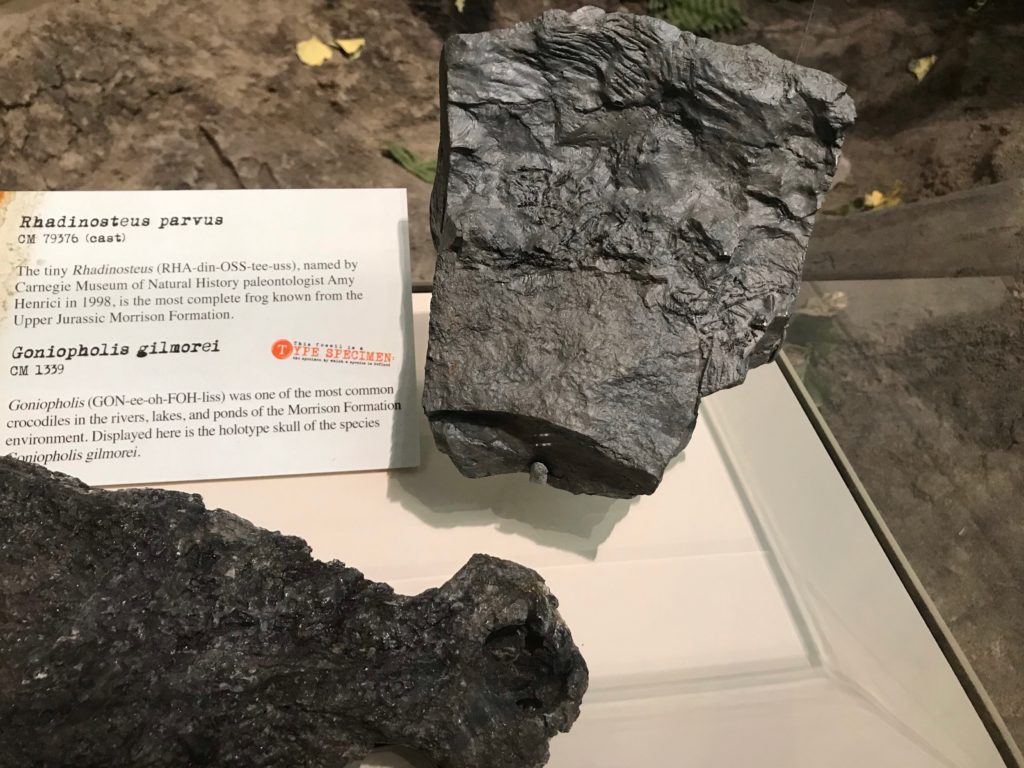

Goniopholis gilmorei

Goniopholis gilmorei was a common crocodile found in the Morrison Formation, in the U.S. West, during the Cretaceous period.

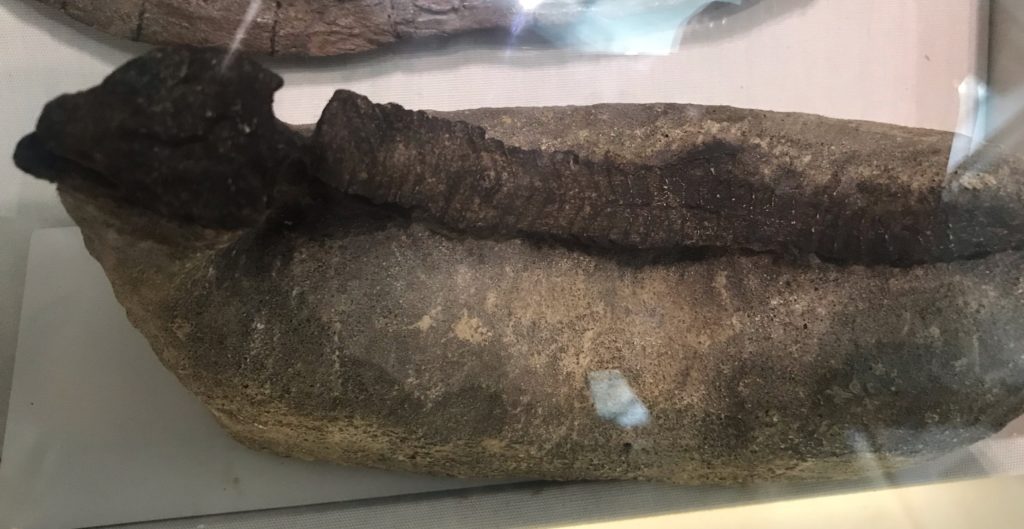

Deinosuchus rugosa

Deinosuchus rugosa was a massive Late Cretaceous crocodile, growing up to 26 feet long and weighing 11,000 pounds. Like modern crocodilians, Deinosuchus was an ambush predator, waiting in shallow water for prey to pass by.