by Mason Heberling

Human activities are changing our very notion of what is “natural.” We are surrounded by nature, no matter whether we are in an asphalt parking lot in Pittsburgh or deep in the Allegheny National Forest. This conclusion was a central theme (and namesake) of the recent exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History titled We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is an interdisciplinary, far-reaching conceptual framework for understanding, managing, protecting, and celebrating our natural heritage in a new era of global human influence on the Earth’s systems.

Is there value to nature in the city? How about the mowed lawn in your backyard? Or the weeds in sidewalk cracks? It’s easy to overlook nature in human dominated environments, but it is something special.

While the Anthropocene as a formal term is quite new, many of the basic concepts behind it are far from it.

I recently stumbled across an inspiring, forward thinking essay by Otto Jennings entitled “Botany Near Home.” I do not know the date or where it was published.

Affiliated with the Carnegie Museum from 1904 until his death in 1964, Jennings made many contributions throughout his career, serving as the Curator of Botany, Director of Education, and eventually Director of the museum. He also was Professor and Head of the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, having advised many students. His legacy remains to this day for his influence on the museum, botany, conservation, and environmental education.

In his short essay, Jennings asserts that you do not need to go far to teach and learn botany hands-on. He writes, “…the teacher need not have to break up regular class schedules or to go to the trouble of organizing a field-trip to some more or less distant place.”

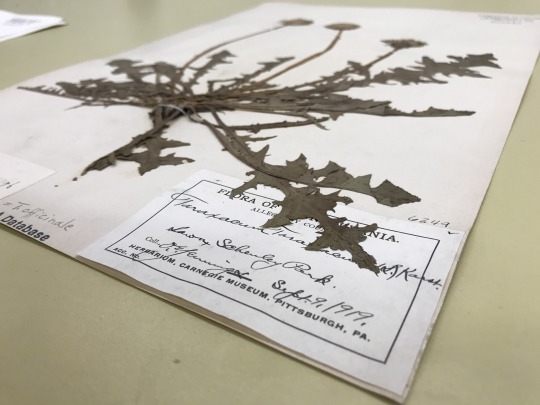

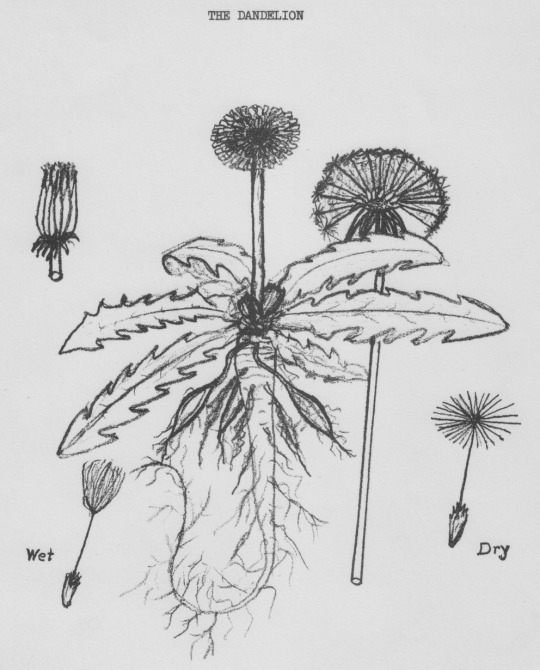

He continues, “Various plants grow in backyards and vacant lots which were not planted there by anyone. How did it get there? Our back in a semi-business part of Oakland, in Pittsburgh, has had ailanthus trees, wild cherries, elderberries, southern fireweed, plantains, smartweeds, asters, a goldenrod, a thistle, and many dandelions. How did they get there? Such a question might well be put to the school children as a quiz contest – and let them work out the answers.” Jennings then focuses the rest of the essay on the fascinating biology of the common dandelion and advocates the use of this often overlooked, common plant to teach botany.

While this basic essay may not seem like much, there is an important point. We often think of “nature” as something far away, something you visit. But indeed, you can find botany near home. And once you look for it, it is a fascinating world. Even the common species aren’t as boring as you might think, once you take the time to look closely.

In the city blocks around the Carnegie Museum of Natural History alone, there are currently 104 species of plants recorded by citizen scientists in iNaturalist. That’s right, 104! And I would presume this is far from a complete inventory.

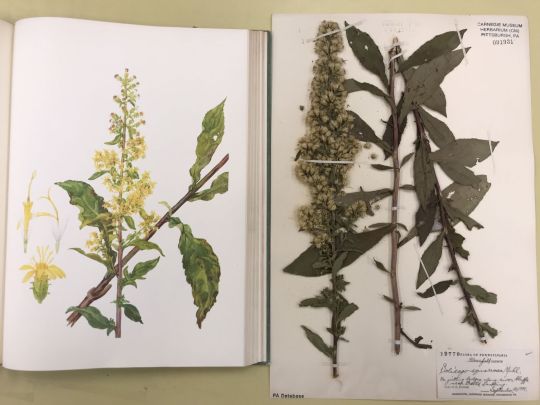

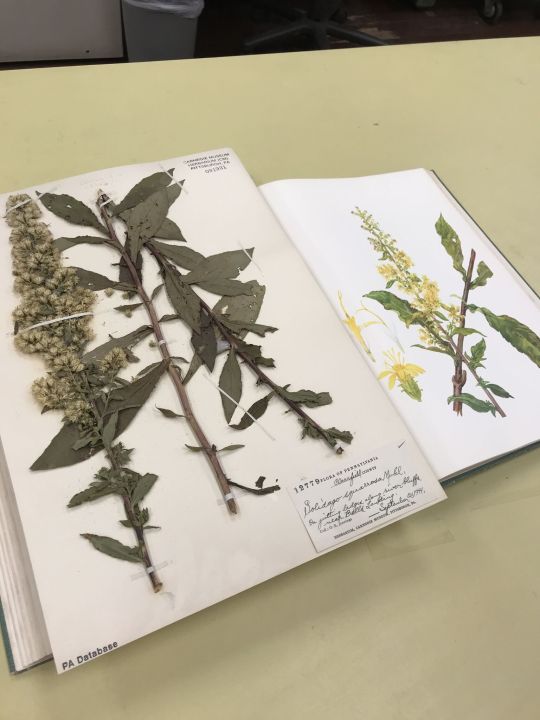

What about urban diversity captured in the museum herbarium? Of the 170,000+ plant specimens collected in Pennsylvania alone, over 15,000 (!) were explicitly described by the collector as growing in a human-made habitat (defined broadly, including words such as urban, sidewalk crack, vacant lot, roadside, railway, waste area, industrial, etc).

Despite the importance of appreciating life in human-dominated environments, it is also important to recognize the inherent and functional value of “pristine” nature. Managing for the “natural” is one of many difficult topics to tackle in the Anthropocene. What exactly is nature? What should nature be? Is there inherent value in all species? What species are priorities to conserve? How do we balance the perceived needs of human society with that of biodiversity?

These are just some of the many questions without easy answers. But as we define our collective future in the Anthropocene, let’s always appreciate “botany near home.”

–

For more on the urban plants of Pittsburgh, be sure to check out the book Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast published in 2010 by Peter Del Tredici. https://librarycatalog.einetwork.net/Record/.b29413795

Also, be sure to check out the recent activity book published by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. It was designed for use by parents and teachers to engage young people with nature, even in the city.

Mason Heberling is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Section of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.

Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have embarked on a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.