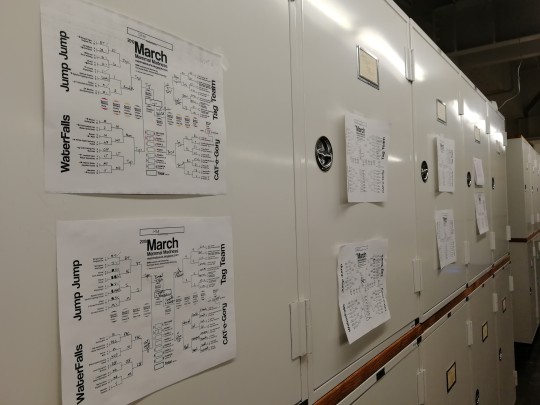

In case you missed it, March Mammal Madness has already started! What you may say is that?

As an alternative to College Basketball’s March Madness, Dr. Katie Hinde, currently at Arizona State University, began a bracket tournament that pits mammals against one another and sometimes other odd creatures.

The Section of Mammals is very excited about this year’s tournament with all staff members having made their predictions. Three of us have picked the Bengal tiger as the ultimate champion, one has the small spotted cat shark, and two others have chosen tag teams (coyote & badger on the one hand and batfly and gammaproteobacteria on the other).

For more details on this year’s tournament, click here.

The only repercussion so far is that our lunch time includes a certain amount of trash talk. One of the upsets in the first round was the streaked tenrec defeating the markhor (a small hedgehog-like mammal versus a large screw-horned goat). The markhor had the advantage of size and home turf, but the tenrec won by poking the markhor in the face with its quills.

John Wible is Curator in the Section of Mammals at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.