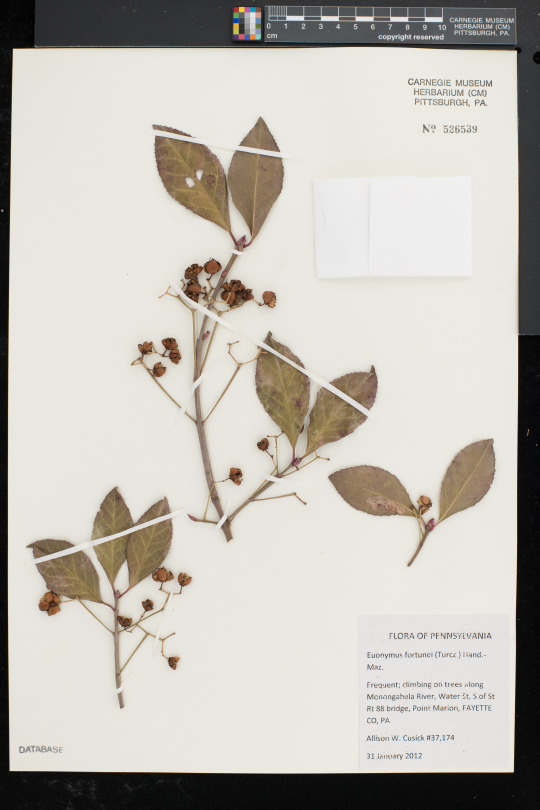

Unnamed, but not forgotten!

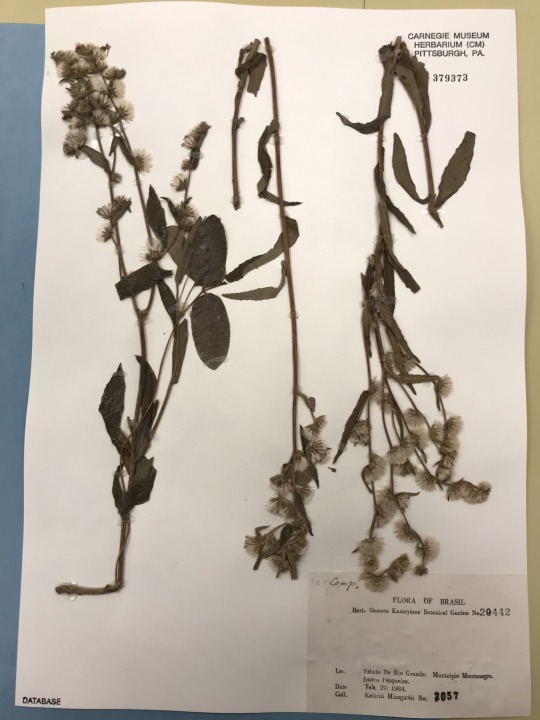

Today, we celebrate the 9th birthday of this specimen collected 36 years ago.

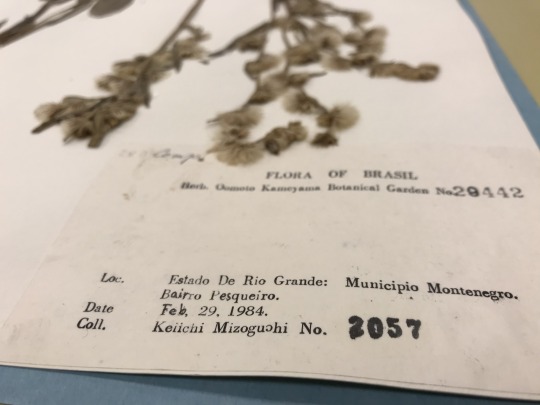

This specimen was collected on leap day, February 29, 1984 in Brazil by Keiichi Mizoguchi.

Fun fact: In the Carnegie Museum herbarium, there are 85 specimens collected on leap day, collected between 1872 until 1990. That’s a lot of leap years!

Aside from it being collected on leap day, the specimen label might seem even more unique. Where most herbarium specimen labels have the species name, this one is blank. A big blank spot. The collector did not identify this specimen, nor has anyone else in the past 36 years (yet). This is an “indetermined” or unidentified specimen. It is filed in the sunflower family (Asteraceae) based on its flowers, but it is otherwise not identified.

We can’t forget about these unidentified specimens. Especially those collected on leap day!

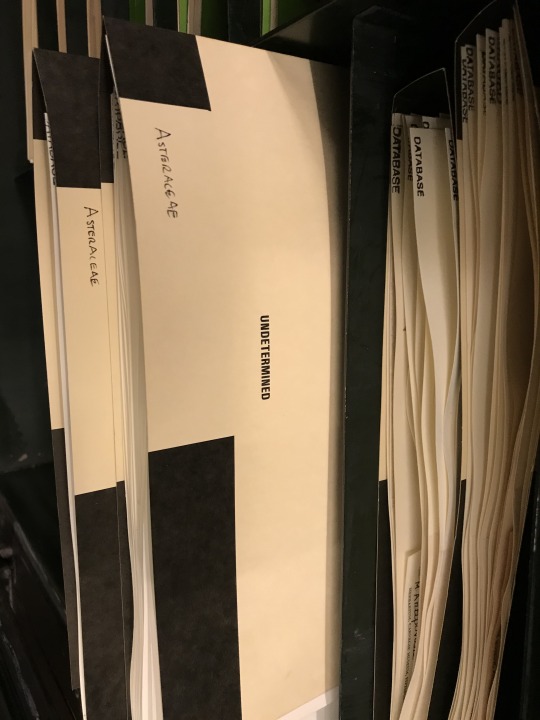

Specimens in the herbarium are arranged by plant family, then genus, then geography (where it was collected), and in nearly every genus, at the bottom of all these folders is a black colored folder labelled “undetermined” (also called “indet.”) that includes those specimens that have not yet been identified to species. Of the over 525,000 specimens in the Carnegie Museum herbarium, about 2% (= 10,588 specimens), are not (yet) identified to species.

This specimen is most likely a member of a species already known to science, but an expert has not yet identified this particular specimen. However, many undetermined specimens may be undescribed (that is, new to science). The name and description of new species (alpha taxonomy) is a major purpose of herbaria. A study in 2010 estimated that of the estimated 70,0000 species yet to be described, over HALF are lying in herbaria right now! They also found that only 16% of new species descriptions were done within 5 years of specimen collection, and 25% of new species descriptions involved specimens that were more than 50 years old!

Study abstract here: http://www.pnas.org/content/107/51/22169.abstract

Taxonomy (branch of science on classification of organisms) is always changing. Species names are changed, what was once thought to be one plant species or family is split into many, and what was thought to be several species is lumped into one. And with further information or upon review by experts in particular plant groups, specimens are determined to be a different species than what the original collector called it. Annotation labels are added to specimens all the time – these labels revise the species listed on the original label. A typical annotation label includes the revised species name and details, the name of the person making the annotation, and the date.

Some specimens can have many annotations, which nicely demonstrates the community culture of science as a process with constant revision as we learn more about the world around us.

Find this specimen here. Check back, maybe it’ll have a species name on it by next leap year!

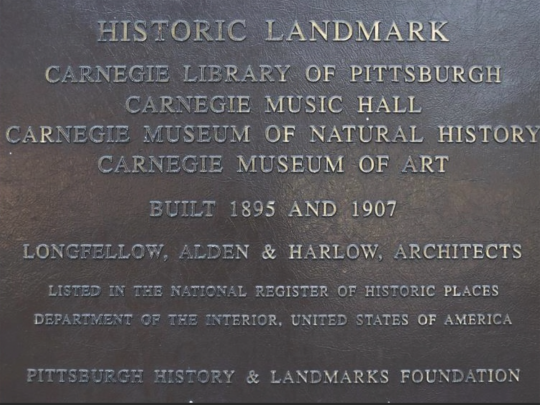

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.