Super Science Meowfest

Cats: The Original Social Distancers

Science is always changing as ideas grow and evolve—it’s one of my favorite things about the topic. During my undergraduate years at Canisius College, I joined a research team to experience this first-hand. We were focused on studying the welfare of shelter cats to find ways to lessen their stress, so they were more likely to be adopted. The project I worked on focused on space requirements in colonially-housed cats and the conclusions are very relevant to current world events. I am lucky enough to have worked with an amazing advisor who has become a very good friend—Dr. Malini Suchak, Associate Professor of Animal Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation at Canisius College and Feline welfare and cognition researcher. I reached out for her personal experience and description of some of the findings of the project:

Although I’ve studied cats for eight years, and animal behavior much longer, the pandemic has offered me a unique, 24 hours per day look into my cat’s life. I’ve found myself fascinated by how he socializes with me on his own terms—at times endlessly “Zoom-bombing” my meetings, demanding attention, and other times disappearing for hours at a time into some secret napping spot I still haven’t found. This independence of spirit at least partially stems from the fact that cats were domesticated from a solitary species, the near Eastern wildcat. In fact, in true independent cat fashion, we didn’t domesticate them; they did it themselves in a process called self-domestication that took place about 9,000 years ago.

Fast forward to 2020, and we have a (sometimes) cuddly companion, living a posh life in the house, sometimes with other cat companions. Cats are interesting because their ability to tolerate (or maybe even like) being around other cats is dependent on them being exposed to other cats early in life. They tend to vary a lot in this regard; while some cats have close friends, most fall somewhere between accepting other cats and barely tolerating their presence.

When they do live together, whether at home or in animal shelters, cats are experts at keeping distance between themselves and others, which might help them cope with too much social contact. They might “time share” favorite resources like a box or a windowsill, where everyone gets a turn at different times of day. They use items in their environment, like shelves, crates and boxes to create “personal space bubbles” and physically separate themselves from others. All these actions help increase their distance, or their sense of distance from other individuals.

In fact, we found that cats living in groups at a shelter kept an average of 6ft (2m) from each other. If that sounds familiar, it’s because that’s the recommended distance we humans should maintain to social distance and reduce the spread of coronavirus. We also found that cats living in groups were no more likely to develop an upper respiratory infection than those housed alone, despite the fact that you would predict exactly the opposite—increased disease-risk is one of the major costs of living in groups. Now, there could be a lot of reasons why the disease rate was the same, but we can’t discount the fact the cats naturally keep the recommended distance between themselves.

Being part of this team changed my life in many ways; I realized collecting and processing data (which is most of research) wasn’t what impassioned me. I found I loved teaching others what the research was discovering instead.

So, here’s hoping you enjoy the rest of Meowfest a comfortable distance from your feline friend!

Abbey Hines is a Gallery Experience Presenter as well as an Outreach Educator and Animal Handler in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department.

Dr. Malini Suchak teaches courses in introductory animal behavior, animal cognition, and animal welfare at Canisius College, as well as researches how nonhuman animals think about other individuals in their social groups.

Related Content

Cat Chat 101: The Basics of Domestic and Wild Vocalizations

Cat Chat 101: The Basics of Domestic and Wild Vocalizations

Whether they are greeting you at the door, asking for a meal, or letting you know you’re interrupting their fifteenth nap of the day, most cats have no qualms about speaking up and telling you how they feel. But, when it comes to vocalizing, your pet actually has more in common with their wild relatives than you may realize.

The way all cat species communicate is different than the methods used by humans; yet the ways they vocalize are effective and deeply significant to each other. Vocalizing helps cats in a variety of ways—from social bonding, to showing off, and even for self-defense. Here are some of the main methods of communication of both wild and domestic cats:

Roaring and Purring

For the most part, big cats (lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars) can roar, but they can’t purr. Cougars and smaller cats (bobcats, ocelots, lynxes, and house cats, among others) can purr, but they can’t roar.

Purring is possible because of tightly connected links of delicate bones that run from the back of a small cat’s tongue up to the base of the skull. When a cat vibrates its larynx, or voice box, it sets the twig-like, bones called hyoid bones to resonating. The hyoid is a U-shaped bone directly above the thyroid cartilage; also known as an Adam’s Apple in humans. No one knows for sure why smaller cat species developed this ability, but one theory is that a mother’s purr helps to camouflage the mewing of her nursing kittens—thus avoiding the attention of possible predators. If you listen to your own cat carefully, you will notice that their purr is one continuous sound that they make while breathing both in and out.

When it comes to big cats and roaring, a length of tough cartilage runs up the hyoid bones to the skull. This tough cartilage prevents purring but gives the larynx enough flexibility to produce a full-throated, terrifying roar. In the case of lions, their roar can easily be heard and “felt” up to five miles away—their deep roar is loud enough to almost reach a human’s pain threshold if they’re standing nearby. Although they can’t purr, lions do have the equivalent (or, in the case of some other big cats, the equivalent of a chuff. But more on chuffing later). Instead of purring, older lions will lowly moan and groan when socially bonding with one another, sometimes trying to drown each other out with their sounds.

Tigers are capable of roaring, but their roar sounds more like an impressively loud growl; a “growl” that can carry for almost two miles. A tiger’s roar can serve multiple purposes. It can be used as a warning to other tigers in their territory or serve as an invitation to potential mates.

Cheetahs are unique when it comes to vocalizations; they purr instead of roar and are in a special cat-category all their own; this is mainly because they can’t completely retract their claws like all other cats. Instead of roaring, they emit a high-pitched sound similar to a canary’s chirp. Cheetahs chirp when they are in distress, want to attract a mate (in the case of females), and when they need to locate each other.

Growling and Hissing

If you have multiple cats in your household, then there is no doubt you have probably heard your fair share of growling and hissing. All cats, both big and small, growl and hiss to some degree. Whether wild or tame, it’s easy to understand the meaning of these two sounds; the cat is not a happy camper. A growl is a raspy, guttural sound that is produced by pushing air through the cat’s vocal chords. Cats growl when they feel threatened (either by another cat or another animal), when they want to tell a pride member to back off, or to claim possession over something like dinner. If the message hasn’t quite been received, hissing usually follows. A hiss is created when a cat forces a short burst of air out through its arched tongue. Some feline experts believe that cats may have developed this defensive habit by imitating snakes; mimicking another species is a survival tactic among many animals. Hissing is primarily used as a last resort before a full-blown attack. But this serpent-like sound can also serve other purposes, such as establishing dominance in a hierarchy or intimidating a prey animal.

Chuffing

Tigers, Jaguars, Snow Leopards, and Clouded Leopards chuff. Chuffing—also called prusten—is the equivalent of a domestic cat’s purr. It is a low-intensity sound that a big cat will emit in short, loud bursts. To vocalize a chuff, air is blown through the nostrils while the mouth is closed, producing a breathy snort. It is typically accompanied by a head bobbing movement. It is often used between two cats as a greeting, during courting, or by a mother comforting her cubs. Chuffing is always used as a non-aggressive signal and helps to strengthen social bonds.

Meowing

Surprisingly, meowing is not expressly reserved for domestic cats. Snow Leopards, Lion cubs, Cougars, and Cheetahs also meow. Meowing can be used to locate each other or simply a request for food or affection.

If there is more than one cat in your home, you may have noticed that domestic cats never meow at each other. House cats use meowing as form of communication with humans and no one else (you lucky human, to have such an honor bestowed upon you).

Just in case you may be new to cat ownership and are not quite sure what your cat is trying to tell you, here is a quick cat-to-human language lesson:

· Short meow—short and high-pitched, this just means “Hi!”

· Multiple meows—can be a sign your cat is happy to see you or wants attention.

· Mild-pitch meow—usually a request such as “Can I please have some food…pretty please?”

· Drawn-out, mild-pitched “mrroooow”—is more of a demand or an early warning of aggression/fear.

· Drawn out, low-pitch “MRRRooowww”—usually a complaint but, can also signal heightened aggression/fear. If agitated for much longer, the cat may lash out.

· High-pitched, loud “RRRROWW!”—is reserved for pain or maximum aggression. In this state, a cat is most likely to lash out at whatever is causing the agitation, fear, or pain.

It’s never much fun in any household when, for whatever reason, your cat(s) work themselves up into such a state that you hear hissing and yowling as the fur flies. But, when all the feline drama is over and done with and your cats have relaxed and returned to contentedly purring, appreciate the fact they took a little time to get in touch with their wild side.

Shelby Wyzykowski is a Gallery Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Cat Adoption Guide

Adding a new feline friend to your household is a process that can be both exciting and scary, especially for first-time cat owners and even the cats themselves. With so many things to consider, it can feel as though a million things could go wrong. Thankfully, there are many things you can do to make the transition as smooth as possible!

Part 1 — Before

In every case, the best way to ensure a new pet adoption goes smoothly is to prepare beforehand. If you are considering getting a cat, there are a few things you should ask yourself first:

1. Am I ready to be responsible? While a new animal is always very exciting, remember that there is more to pet ownership than having a cuddly companion. It costs money to care for a pet its whole life; food, toys, litter, and veterinarian visits can add up. Caring for a pet, especially when you first bring them home, also takes time to ensure the transition runs smoothly. Do you have room in your budget and schedule for pet care? If you adopt a cat with special needs, will you be able to provide specific care for them?

2. Will this addition go over well? Make sure all members of your household—including other pets—can handle the change!

3. What do I know about caring for a cat? If you are going to be a first-time cat owner, take some time to read online about the sort of care your new friend will need. Take time to research what different needs cats may have— adopting a kitten can be different than adopting an adult or senior cat. Cats with special needs may also require different sorts of care.

Once you’ve determined that cat ownership is right for you, you can begin to prepare your home and search for your new friend! Here are a few things you can do before you bring your cat home to make the process more comfortable:

Figure out your space. Determine where you can put things like litter boxes, food, and beds. If you have other pets, make sure you can set aside a room away from them for your new cat to spend time in for the first few days. Make sure the area has enough space for their litter box, food (which should be placed away from the litter box), and areas for your new friend to hide in so that they feel safe and secure.

Determine your game plan. Who will be there when you bring your new cat home? If you have small children, it is always a good idea to remind them that your cat may need their own space for a few days before they want to come out and play. If you are a first-time pet owner, or if you’ve moved to a new area, make sure to do some research beforehand to choose what veterinarian in your area you plan to go to with your cat, and be prepared to make an appointment for soon after you have adopted your cat.

“Kitty-Proof” your home. On the day you know you will be bringing your furry friend home, make sure the area you plan to let them adjust in has no open windows, dangling or exposed electrical cords, dangerous chemicals, or delicate objects.

Part 2 — During

Remember when choosing your new family member that all cats have different personalities and needs. Are you prepared to care for a kitten, or would an adult or senior cat be a better fit for your family? Are you able to properly care for a cat with special needs? Are you looking for a cat who doesn’t mind sharing their home with other pets or children, or are you looking for just one pet?

Make sure when you’re adopting your cat that you communicate these things to the people or group you are adopting from. Often, these groups have a great understanding of their cats and can help to match you with an ideal companion. It is also important that you know the medical history of your new cat— are they spayed or neutered? Do they need to take medication? What is their vaccination history? The place you are adopting from may also be able to tell you what sort of food and treats your cat likes, which can take the guesswork out of buying their diet.

Part 3 — After

This part can often be the most stressful for both people and pet; a new space, filled with new sounds and smells, can be confusing and scary for a cat. Experts often recommend doing the following:

Set up a vet visit. It is always a good idea to take your new pet to the vet about a week after their adoption. Make an appointment with the vet of your choice and be sure to take you cat’s medical records with you.

Set a schedule. Try to feed your cat at the same time every day. A routine is a good way to make your cat feel at ease in a new space. It is normal for a cat to not eat much at first, but if you notice that they have not eaten or drank for more than a few days, contact your veterinarian.

Give them their space. Remember that area you decided to set aside for your new friend? Allowing your cat to have one area of the house to get used to and feel comfortable in can lower stress for everyone involved. If you have other pets, make sure you do not introduce them to your new cat for at least the first few days. Introducing pets can take a long time; be sure not to rush the process. Additionally, allow your cat to approach you and other people within the room when they feel comfortable doing so. It is not uncommon for your furry friend to hide for a few days in a new environment until they feel more comfortable.

Establish trust. Recognizing a friendly face can make your cat feel more at ease. Sitting on the floor and allowing your cat to get used to you and your smell can build a relationship that makes them feel comfortable. Remember to always let your cat come to you; do not chase or corner them. Speak in a soothing voice and be sure to tell your new kitty how happy you are to have them in your family!

Allow them to move at their own pace. Once your kitty has begun feeling comfortable in the space you gave them, determine how to safely allow them to explore the rest of your home. Again, make sure that the spaces your cat is in are safe for them; close your windows, make sure chemicals are out of reach, and make sure your cat cannot chew on cords or access human food that could be harmful for them.

Provide Enrichment. Many cats love to play and being active is an important part of keeping your cat happy and healthy. Provide them with plenty of toys that they can bat around, chew, pounce on, and scratch. Over time, you may start to notice which toys your cat likes best. Play time is also a good time to build a relationship with your cat— just remember not to overwhelm them. Crafting home-made toys for your cat can also be a great family activity, but remember to always use materials that are safe for a cat to play with. Many websites offer free tutorials on how to make great cat toys!

Remember that patience and respecting boundaries are two key things to ensure your new family member adjusts well to your household. Giving your cat the opportunity to take things at their own pace removes a lot of the stress that the both of you may feel. Planning ahead to make sure your cat receives quality care means that they can enjoy their new forever home to the fullest!

Emma McGeary is a Gallery Experience Presenter as well as an Outreach Educator and Animal Handler in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Meowfest: Cat Whisker Activity

Have you ever seen a cat investigate a space they’re interested in by putting their head in the space, only to back up and change their mind? A cat has a built- in measuring tape that lets them know when their curiosity may just get them stuck in a space that is too small for their bodies—their whiskers. A cat’s whiskers are the same length as the width of their body. They have small heads, which means going into a space head first without knowing if the rest of their body will fit can be problematic. Luckily, they know if their whiskers touch or bend upon entering a space, it is too small for their body!

Let’s Investigate

You can create a set of cat whiskers with a few items at home that can help you get a hands-on look at how a cat uses its whiskers.

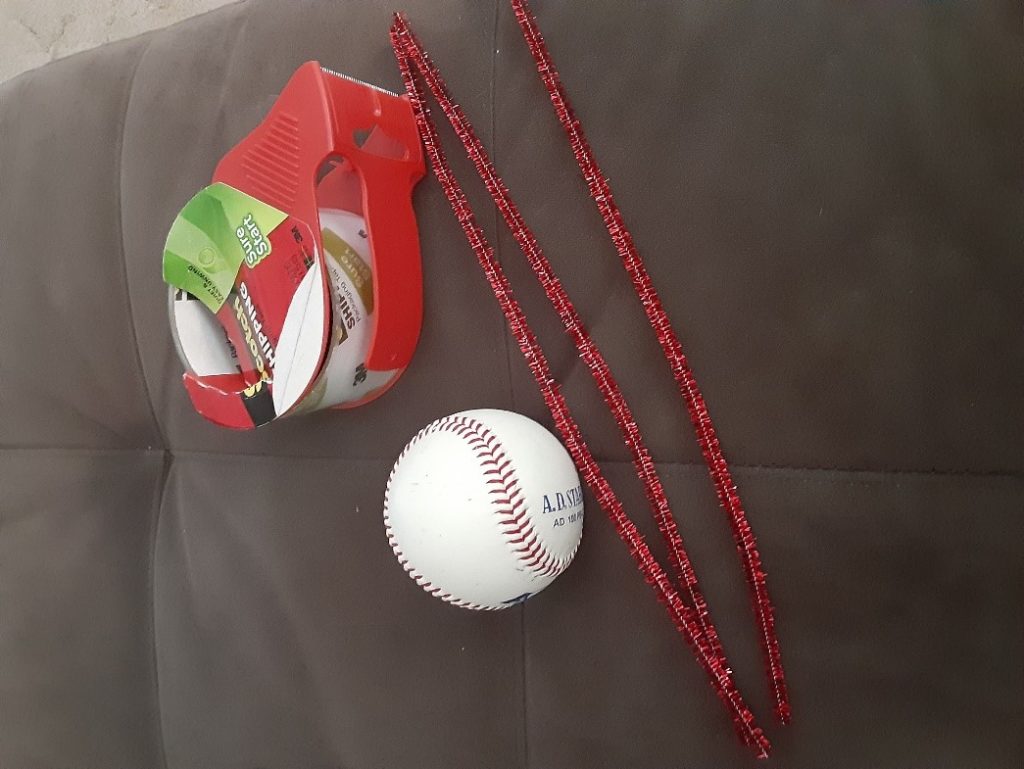

Materials Needed

Directions

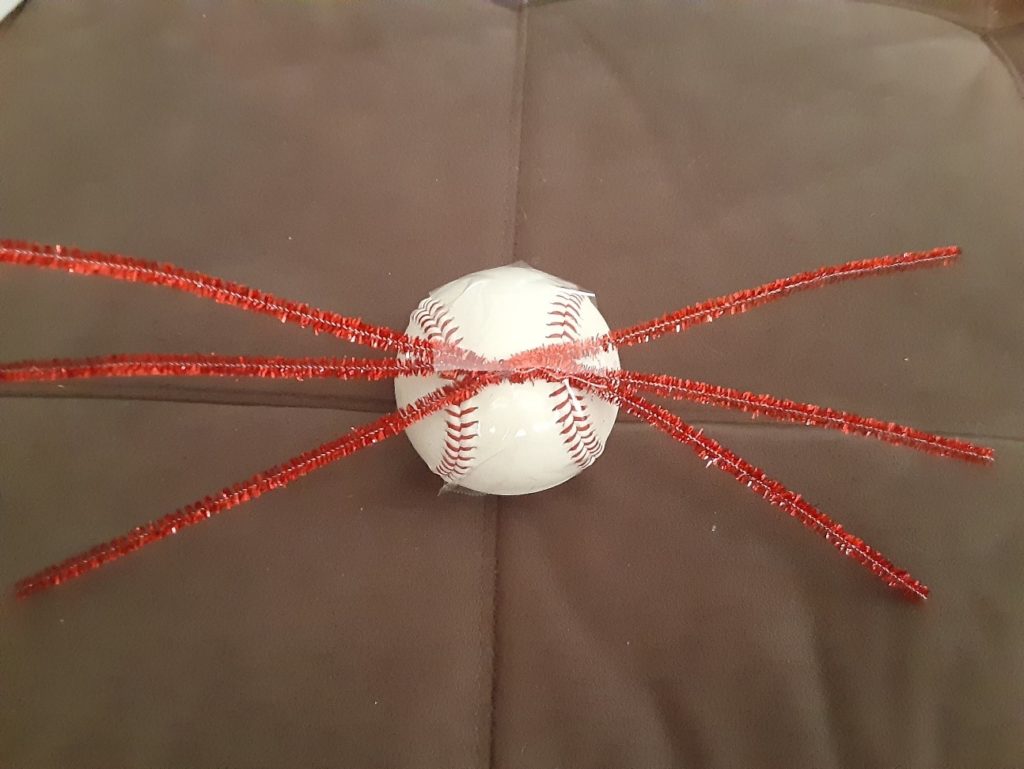

- Twist pipe cleaners together to form a set of whiskers. Trim them into desired length, but make sure they are symmetrical—meaning they are the same length from the center to the ends on both sides.

- Tape the center of the whiskers to the ball.

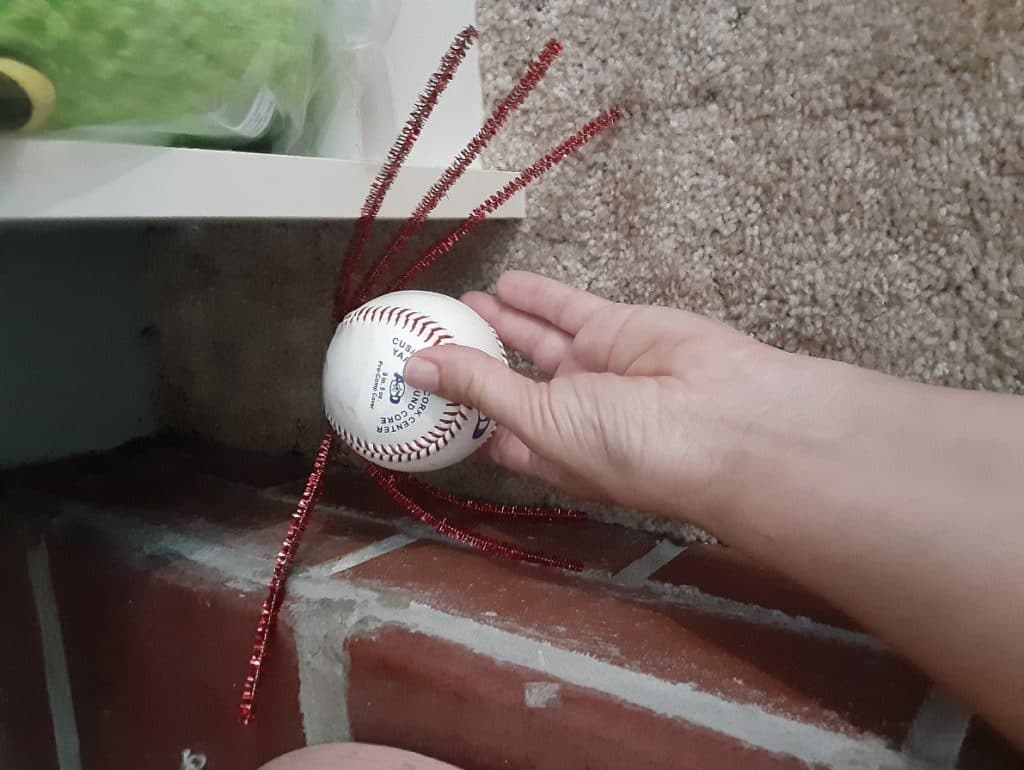

- Use the ball and whiskers and see if it can fit through tight spaces just like a cat. If the whiskers touch the sides of a space, bend or get pushed back, the space is too small for a cat!

Collect Data

Take notes, or pictures on where your cat whiskers will fit. What spaces would your imaginary cat be able to fit into and where would your cat need to back out of?

Meowfest: Sabertooth Tiger

If you ever think you’ve found yourself in a sticky situation, it doesn’t compare to what this sabertooth tiger found itself in. This specimen of Smilodon, otherwise known as a sabertooth tiger, the Dire Wolf, and Harlan’s Ground Sloth at the museum were recovered from excavations at the La Brea Tar Pits.

Smilodon itself is the general name for three separate related species: Smilodon populator, Smilodon fatalis, and Smilodon gracilis. Despite their name, they’re not closely related to tigers or other big cats in the genus Panthera, which also includes lions, leopards, and jaguars. The three species mostly differ in size—while Smilodon gracilis typically weighed in at around 55-100 kg (100-220 lbs), Smilidon fatalis tipped the scales at 160-280 kg (350-600 lbs); approximately the same weight as a Siberian tiger.

All three species of Smilodon have elongated canine teeth. Some specimens have teeth measuring up to 11 centimeters (4.33 in.). However, these teeth are incredibly fragile. If the Smilodon were to hunt the same way as modern cats, they would have broken their canine teeth. Instead, it’s thought Smilodons would use their upper body strength to tackle the intended prey and then use their canines to puncture and tear away meat. Due to the distribution of fossils found, it is believed that they were most likely pack hunters.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History is proud to feature a Smilodon fatalis specimen, which had a roundabout journey 2,000 miles and approximately 11,000 years in the making.

It all began at the La Brea Tar Pits—a series of naturally occurring asphalt pits where petroleum oozes from the ground. What makes the pits at La Brea unique is the fact they have been continuously active for 50,000 years. As history has progressed, modern-day Los Angeles has grown around them. The pits are now one of the only paleontological sites located inside of a major city in the world.

The Rancho La Brea Tar Pits are a virtual treasure-trove for fossils from the Ice Age. Over 100 excavations since the early 1900s have resulted in the recovery of over 3.5 million fossils from all manner of species, including over 2,000 individual sabre tooth tigers. This is due to the unique fossilizations process created by the pits themselves. As the tar oozes, pools, and warms on the ground, it becomes sticky; prey mammals can easily become stuck in as little as four centimeters (1.57 in.) and unable to move. A strong and healthy animal might be able to escape, but for the majority trapped in the tar, it was only a matter of time until they succumbed. Sometimes, a passing predator would hear a stuck animal and try to seize them first (such as Smilodon). This would often result in the predator becoming stuck as well, and both predator and prey would be found well-preserved thousands of years later.

Even today, the Rancho La Brea site is still actively producing fossils. A variety of flora and fauna have been preserved here, allowing us to have an unparalleled look at species from the end of the last major Ice Age. By studying these fossils from the past, scientists in turn can learn how things like climate change may affect us in the future.

Andrew Huntley is a Gallery Presenter in CMNH’s Lifelong Learning Department, as well as part of the Animal Husbandry staff for the Living Collection. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.