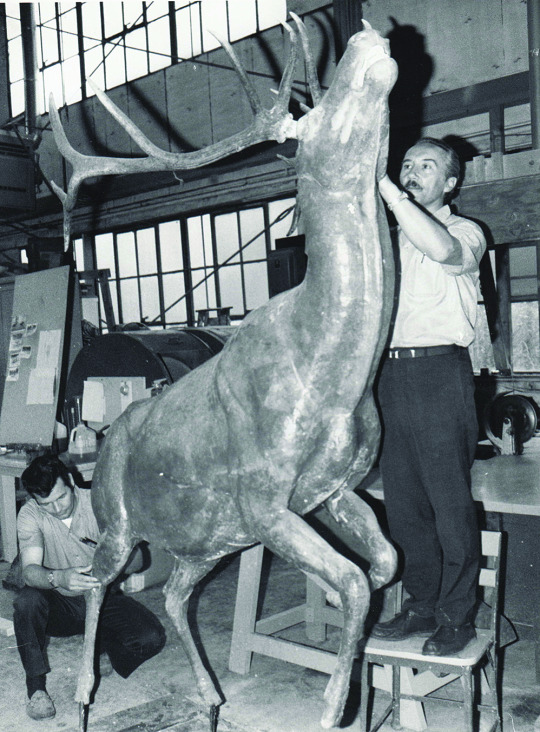

A visit to the wildlife dioramas at Carnegie Museum of Natural History is an opportunity to repeatedly admire the illusions created by teams of skilled taxidermists. None of the featured creatures are alive, but many of them appear to have just paused. Some, such as the pronghorn antelope, pictured above, even seem to be frozen in motion.

In several three-dimensional scenes, where the animal subjects are predators or scavengers, the taxidermists involved in creating the exhibit faced another challenge – presenting the preserved remains of a dead animal as a dead animal. The task, as the somewhat gory details in the pictures below attest, is undoubtedly more difficult than it sounds.

A dead salmon is front and center in the Alaskan Brown Bear diorama, and the pink flesh the cubs are consuming doesn’t look much different than what’s available at supermarket fish counters.

In the Hall of African Wildlife there’s no blood visible on the Lesser Egyptian Jerboa under fennec’s paw. The curled position of the prey’s feet and back legs indicate the struggle with the big-eared fox is over.

In creating life-like mounts, taxidermists use glass eyes of the proper shape, size, and color. The glass eyes appear to have lost their luster for the seal that serves as a prey detail in a Polar Bear diorama.

In one of the oldest dioramas within the Hall of North American Wildlife, the centerpiece presence of a dead bull elk indicates the role of both California Condors and Turkey Vultures as scavengers.

Taxidermy details that indicate the elk’s browsing days are over include dull eyes and a lolling tongue. The tricks of taxidermists are important when they help to explain the role of predators and scavengers, the bedrock biological principle of life from death.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.