by Tim Pearce

Chemicals in our medications, supplements, foods, and beverages often pass through our bodies and wind up in our wastewater. Antidepressants are one of the more common pharmaceuticals in wastewater, and in some samples, concentrations of the stimulant caffeine exceeded those of pharmaceuticals (Raj et al. 2021). Although treatment plants can remove more than 50% of caffeine, the enormous popularity of caffeine consumption by humans results in such large levels of this chemical in wastewater that caffeine is sometimes used as an indicator of human-caused pharmaceutical pollution. These chemicals, along with our vitamins and other food additives, can affect freshwater organisms.

In this blog, I focus on two common chemicals: Prozac (fluoxetine) and caffeine (e.g., coffee, tea).

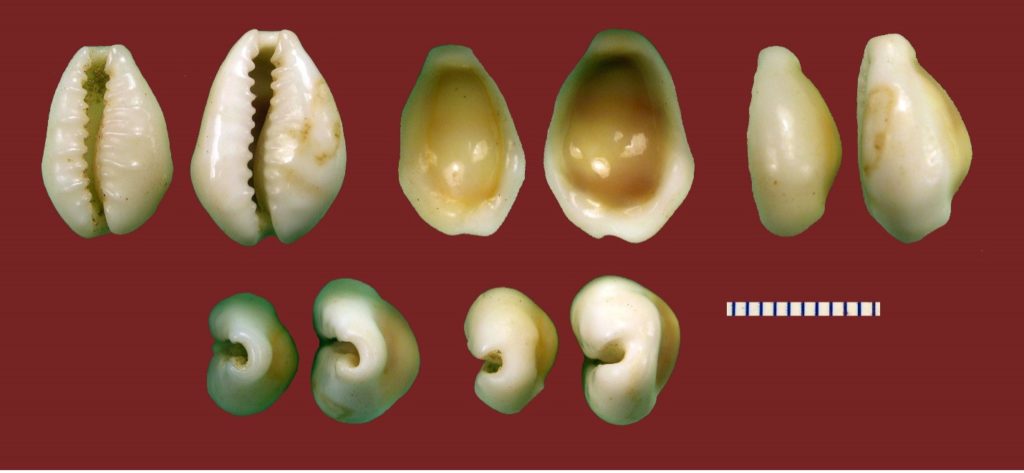

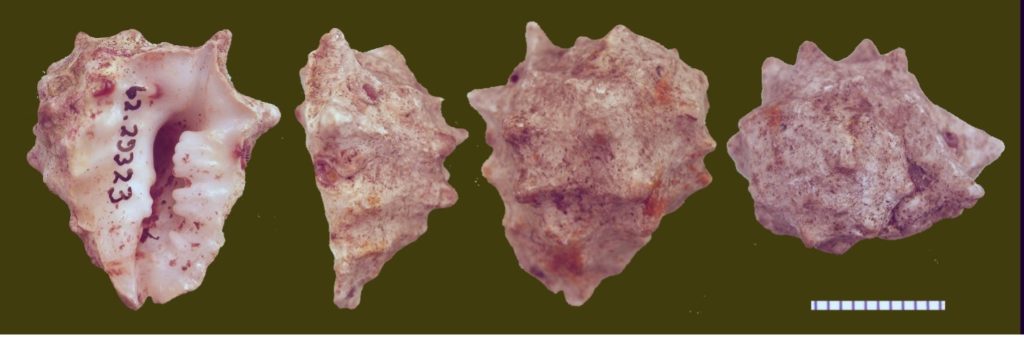

Prozac in low concentrations stimulates reproduction in marine and freshwater bivalves (Fong & Ford 2014), as well as in some freshwater snails, including the invasive New Zealand mud snail (Pomatopyrgus antipodarum). Interestingly, high concentrations of Prozac decreased reproduction in the snails.

Clams on Prozac release gametes or young (Fong & Ford 2014). Small freshwater pill clams (Sphaeriidae) brood their young, and Prozac stimulates the release of these brooded offspring. In freshwater mussels, Prozac stimulates release of their larvae. Our knowledge of this effect can be used to augment propagation efforts to support recovery of endangered freshwater mussel species, but only with a clear understanding of these fascinating creatures’ full reproductive cycle. As part of their development, freshwater mussel larvae temporarily attach themselves to the gills of fish. If Prozac in the water of a natural setting stimulated larval release at times when fish hosts were absent or the larvae were too immature to attach, then the Prozac would be counterproductive to mussel reproduction.

Caffeine negatively affects marine bivalves by inducing oxidative stress (Júnior et al. 2019), leading to degradation of cell membranes (Silvia et al. 2022). When exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of caffeine, the freshwater clam Corbicula fluminea experienced physiological changes, including DNA damage (Aguirre-Martínez et al. 2015). Caffeine might have less effect on freshwater snails. One study on the freshwater snail Helisoma trivolvis showed little effect of caffeine on adult survival, but normal embryonic rotation in developing eggs was slowed at higher caffeine concentrations (Sanchez & Prezant 2016). (The caffeine used as a slug repellent in terrestrial agriculture is in much greater concentrations than that found in wastewater.)

If you needed another reason to reduce your consumption of pharmaceuticals and caffeine, the fact that it affects reproduction in freshwater creatures could be a consideration.

These findings about anti-depressants in our wastewater give new meaning to the phrase, “Happy as a clam.”

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Literature Cited

Aguirre-Martínez, G.V., DelValls, A.T. & Martín-Diaz, M.L. 2015. Yes, caffeine, ibuprofen, carbamazepine, novobiocin and tamoxifen have an effect on Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 120: 142–154.

Fong, P.P. & Ford, A.T. 2014. The biological effects of antidepressants on the molluscs and crustaceans: a review. Aquatic Toxicology, 151: 4-13.

Júnior, C.A.M., Luchiari, N.C. & Gomes, P.C.F.L. 2019. Occurrence of caffeine in wastewater and sewage and applied techniques for analysis: a review. Eclética Química Journal, 44(4): 11-26.

Raj, R., Tripathi, A., Das, S. & Ghangrekar, M.M. 2021. Removal of caffeine from wastewater using electrochemical advanced oxidation process: a mini review. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 4: 100129.

Sanchez, D. & Prezant, R.S. 2016. Influence of diphenhydramine HCl and caffeine on embryonic development and adult reproductive success of the freshwater gastropod Helisoma trivolvis. American Malacological Bulletin, 34(2): 92-102.

Silvia, S., Cravo, A., Rodrigues, J., Correia, C. & Almeida, C.M.M. 2022. Potential impact of UWWT effluent discharges on Ruditapes decussatus: an approach using biomarkers. Advances in Environmental and Engineering Research, 2(2): doi:10.21926/aeer.2102015 [18 pp].

Related Content

Clams In the Concrete! How Old Is This Sidewalk?

Stalking the Freshwater Sponges of Western Pennsylvania

The Zebra Mussel and the Shopping Cart

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Pearce, Timothy A.Publication date: June 10, 2022