by Travis Olds, Assistant Curator of Minerals

March 4, 2025

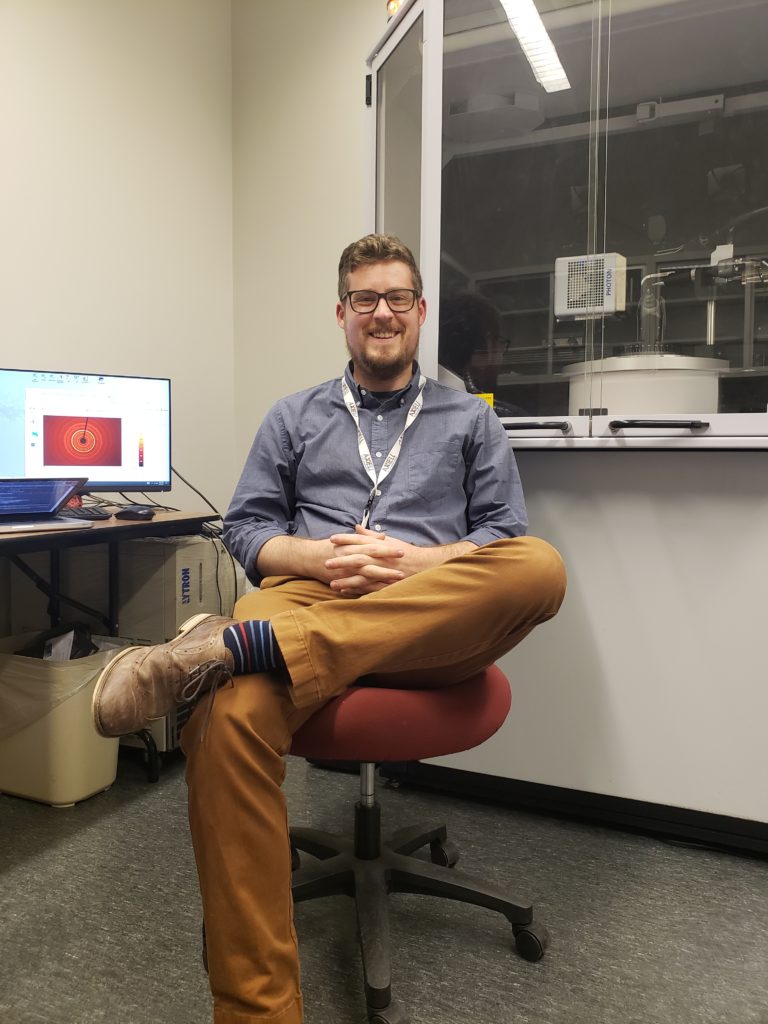

I am pleased to announce Michael J. Bainbridge as the winner of the 2024 Carnegie Mineralogical Award. Established in 1987 through the generosity of The Hillman Foundation Inc., the award honors outstanding contributions in mineralogical preservation, conservation, and education.

Michael is the Assistant Curator of Mineralogy at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Over the course of his career, he has elevated the field of mineral photography, published in leading mineralogical publications, and contributed to groundbreaking works such as Minerals of the Grenville Province: New York, Ontario, and Québec.

Michael has blended art and science to preserve and showcase the beauty of minerals, inspiring collectors and researchers alike. He has immortalized some of the rarest and best-of-species minerals, and this award recognizes the many wonderful contributions he has made to mineral heritage through his lens.

Among his achievements, Bainbridge’s mineral photography has been featured in important works, such as The Pinch Collection at the Canadian Museum of Nature, and numerous articles in Rocks and Minerals and The Mineralogical Record. His work has ensured that specimens of scientific and cultural significance are preserved and appreciated by future generations. As a co-author of Minerals of the Grenville Province, Bainbridge helped document the mineralogical heritage of one of North America’s most storied geological regions. His contributions to Mindat.org and numerous mineral symposia have further enriched the global mineralogical community.

“I love to teach, and I love to tell stories, but I think both are fueled by a desire to learn for myself,” said Michael, reflecting on his achievements. “I’ve always been technically minded but artistically inclined, so combining my passion for minerals with my love of photography has proven the perfect vehicle for me to pursue and share both the scientific and the aesthetic. It has afforded me access to some of the world’s great collections and sparked collaborations with some of the community’s most influential amateurs and professionals alike.

“Among my proudest accomplishments, the Pinch book stands in high relief. Pushing the boundaries of photomicroscopy in documenting some of the smallest and rarest specimens of Mont Saint-Hilaire has been both challenging and rewarding. Ensuring top-notch reproductions for Lithographie’s publications has proven a similarly worthy endeavor. The significant finds I have made as a field collector are also close to my heart. But seeing new people come to the hobby through doors I have helped to open—whether through the Recreational Geology Project or co-founding the new Ottawa Valley Mineral Club—has perhaps been the most rewarding of all.

“More than anything, I am grateful for the many opportunities to share what I have learned along the way. And now, I look forward to the next chapter in my career as I assist in curating Canada’s national collection at the Canadian Museum of Nature. I am truly honored and humbled by this recognition of my small part in helping to present and preserve the world’s mineralogical heritage for future generations.”

I had the honor of presenting the award to Michael at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show on February 15, 2025. Congratulations, Michael!

2025 Carnegie Mineralogical Award

Nominations are now being accepted for the 2025 Carnegie Mineralogical Award, and the deadline is November 15, 2025. Eligible candidates include educators, private mineral enthusiasts and collectors, curators, museums, mineral clubs and societies, mineral symposiums, universities, and publications. For information, contact Travis Olds, Assistant Curator, Section of Minerals & Earth Sciences, at 412-622-6568 or oldst@carnegiemnh.org.