by Kevin Keegan and Vanessa Verdecia

Kevin Keegan, Collection Manager of Invertebrate Zoology (IZ), and Vanessa Verdecia, Scientific Preparator for IZ, recently returned from a ten-day long crash course on moth and butterfly (Lepidoptera) taxonomy, systematics, natural history, specimen collection, and specimen preparation/curation in the beautiful Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona. The course includes both classroom time and field experiences at the American Museum of Natural History’s Southwestern Research Station.

The biological richness of the setting was ideal for learning about moths and butterflies. The Chiricahuas are one of the Sky Islands of the North American desertss, a term biologists use to describe mountains that abruptly rise high enough from the surrounding territory to support wildly different habitat on their upper flanks and summit. Because each range is surrounded by lowland desert, many mountaintop animals are isolated on what are effectively islands of high elevation.

Attending the Lepidoptera Course as an Instructor

Kevin attended the program as an instructor and gave two lectures: one on the amazing ways caterpillars deceive their predators to avoid getting eaten, and another on the taxonomy/systematics, identification, diversity, and natural history of a massive group of moths collectively called the Noctuoidea or the owlet moths(there are about 40,000 described species of owlet moths in the world).

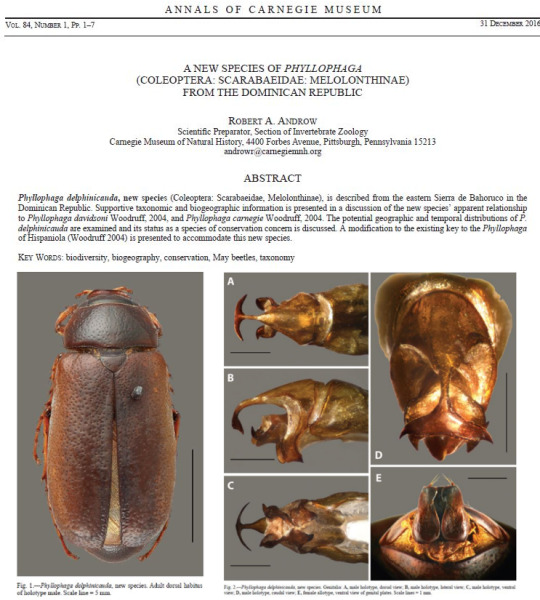

When he wasn’t teaching, Kevin was able to collect many species of owlet moths for study and incorporation into the CMNH IZ collection. He will soon be working with these specimens in the museum’s Molecular Lab, extracting and sequencing their DNA, and adding it to a large dataset he and other owlet moth researchers around the world have built over the last decade. With this DNA data, Kevin will be able to build evolutionary trees to determine the proper placement for these species in the tree of life, a determination that will also reveal whether any of the specimens he collected are of species new to science.

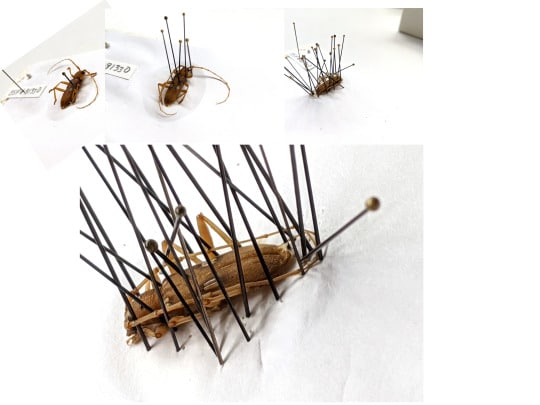

In addition to classroom time, instructors organized daytime and nighttime field experiences, including hikes to look for butterflies and caterpillars, and setting up light sheets where students could observe and collect any moths attracted to the lights. Instructors also set out traps each night to collect moths in bulk for students to identify and sort into taxonomic groups. Moths collected by these efforts were also used by students to practice preparing museum-quality specimens.

Instructors and students also had plenty of time to get to know one another outside of scheduled activities. All meals were served communally in the research station dining hall, which allowed for extended conversations about moths and butterflies, biogeography, the history of lepidopterology, and numerous other topics.

Attending the Lepidoptera Course as a Student

Vanessa attended as a student and learned a lot even though she already has extensive field experience and training in specimen handling from her work at the museum. Vanessa found it wonderful to meet experts and professors from around the country who came together to teach the course. She also enjoyed the formal training and opportunity to learn how to identify different groups of moths by processing moth samples in the company of both experts and students.

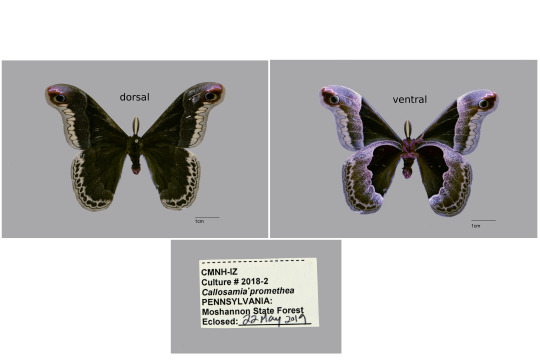

She brought back four boxes of moths for our IZ collection. Over the next several months she will be preparing and labeling all the specimens. Even though the course was about moths and butterflies, other groups of insects sometimes merited attention. Because the light sheets attracted many amazing beetles along with the moths, Vanessa collected two dozen small beetle specimens for the beetle experts on our staff. She also learned new techniques in spreading the wings on moths and butterflies, how to dissect specimens to be able to examine them under the microscope, and the latest information about identifying and classifying moths.

Kevin Keegan is Collection Manager and Vanessa Verdecia is Scientific Preparator for the Section of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Is This Butterfly Blue or Green?

Working with the Type Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Keegan, Kevin; Verdecia, VanessaPublication date: September 13, 2022