by Melissa Cagan and Hannah Smith

In the fall, many animals begin to prepare for winter. Squirrels collect food, groundhogs eat extra food to store as fat, birds migrate to warmer regions…but what do frogs do? Although frogs and toads don’t seem to make any special preparations for the approaching cold, they survive extraordinarily cold temperatures every winter. How do they manage this?

A Long Winter “Nap”

Like other amphibians, frogs and toads are cold-blooded. This means their body temperatures change to match the temperatures of their environment. When winter comes around, frogs and toads go into a state of hibernation. They find a place to “sleep” through winter and slow their metabolism, heart rate, and breathing rate to conserve energy. Frogs and toads rely on two different hibernation strategies depending on whether they spend more time on land or underwater.

Beneath the Icy Ground

Aquatic species, such as the green frog and the bullfrog, rest on pond or river bottoms. So long as the water doesn’t completely freeze, frogs or underwater toads will be able to survive the winter…by breathing through their skin! If these animals buried themselves in mud, they would not be able to absorb enough oxygen. Species that spend more time on land however, such as the American toad or the spring peeper, find drier places to sleep the winter away. Since the ground surface can freeze when temperatures drop dramatically, land frogs and toads need to find places that protect them from snow or frost. This may require a frog or toad to dig deeply enough into the ground that they reach below the frost line – around 50 cm. or more than 20 in. deep!

Frogging Awesome!

Frogs and toads are much tougher animals than you might imagine. Next time you see a frog or a toad, give them a tip of your hat – they are exceptionally hardy (resilient) creatures!

Frozen Frogs

A few, unique species of frogs have found a different way of dealing with cold temperatures. These frogs, like the wood frog and some tree frogs, actually freeze part of their body! These special creatures are able to freeze around 40% of their body’s water content. In this state, the frogs don’t breathe, have no heartbeat, and stop all blood flow. Once spring comes, the frog thaws its body and comes back to life!

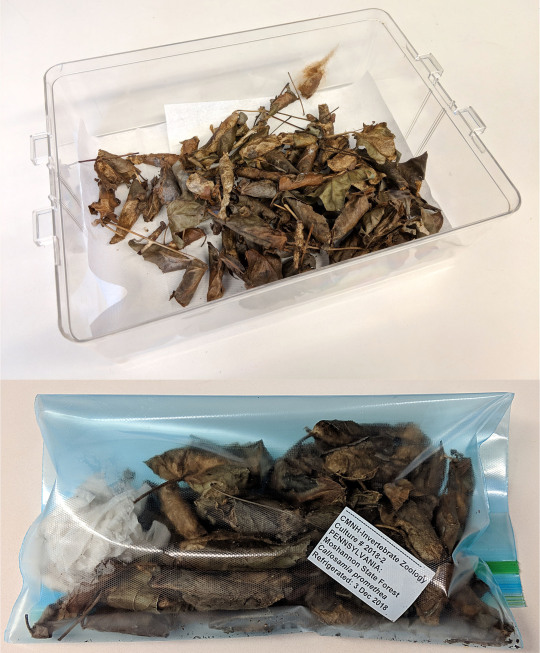

Can You Find the Frogs?

Frogs are great at hiding amongst their environment. They often hide in reeds, plants, and on the banks of ponds or other bodies of water. There are frogs hiding in each of these photos…how many can you find?

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is a pitfall trap?

Trick or Tweet! Clever Creature Disguises

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Cagan, Melissa; Smith, HannahPublication date: March 20, 2019