by Rosie Spinola

Before my science-focused internship at Powdermill Nature Reserve, I was a virtual stranger to the forests of Appalachia. Although I’ve lived in western Pennsylvania my entire life, and frequently enjoyed exploring the woods in my hometown, often, I was simply not tuned in to the diversity and intricacies of the world all around me. My short tenure at Powdermill abruptly changed that perspective. During my internship I had the pleasure of participating in a wide variety of projects and studies, each one an eye-opening learning experience.

The internship began with a crash course in tree identification from my mentor and fieldwork partner, Andrea Kautz. Vegetation surveys were the bulk of the work performed this summer in terms of both the physical labor required and the amount of information we collected. Trees, saplings, shrubs, logs; notations about the location, size, and abundance of each instance contributed to a years-long study of the forest.

One of the major changes that we have been able to track over the years is the cataclysmic effects of the invasive Emerald Ash Borer. The Emerald Ash Borer is an invasive beetle from northeast Asia that lays its eggs in the bark of ash trees. The eggs develop into larvae that eat the cambium of the ash, destroying the tree from the inside out. Where once swathes of Powdermill land were defined by their large white ash trees, you would be hard-pressed to find a single one in today’s forest. The dead ash trees leave a hole in the canopy in their wake and, to the endless consternation of those attempting to survey the area, invasive thorny species move in.

The greatest love of my life is animals, and I got to get very up-close and personal with them when Dr. Walter Meshaka visited to perform herpetology studies. One of the studies he conducted was on snake fungal disease in eastern milk snakes (Lampropeltis triangulum triangulum). Data collection in the field involved capturing individual milk snakes from beneath strategically placed metal coverboards where the reptiles had taken shelter, swabbing their skin to obtain the DNA of the skin microbiota, and then releasing them. Walter allowed me to contribute not only to the swabbing process, but to the risky business of capturing the snakes. I quickly discovered that milk snakes have a spectrum of personalities, from the patient, perfect subjects to the ornery and bitey.

While Walter was here, I was also offered the opportunity to aid him in studying another class of herps: salamanders. Strategically placed coverboards were again critical tools in the study, this time wooden, rather than metal, and placed near wetlands and streams instead of near open fields and meadows. The purpose of this study was to describe the species diversity and density of native salamander species. From our data in June and July, it appears the most abundant salamander near Powdermill’s streams is the charismatic Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus ochrophaeus).

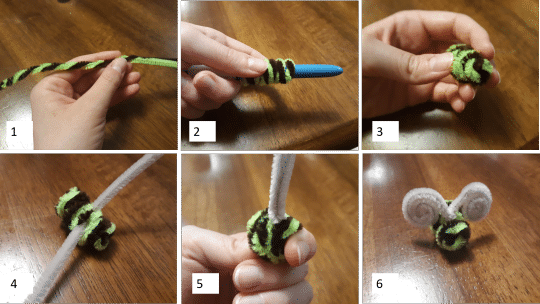

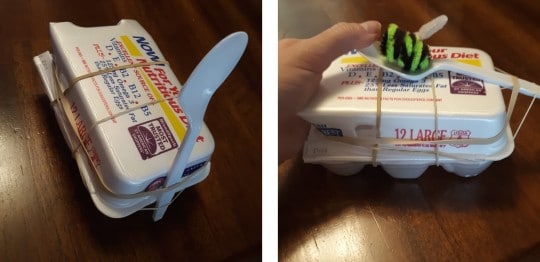

When working with Andrea, an entomologist, you can be sure that insects will be a large part of your life. We began the summer working with a personal favorite: honey bees! Powdermill maintains two hives on its property. The structures are kept healthy with supplemental food, an electrified exclosure fence (to keep out any sweet-toothed bears), and formic acid treatments to control Varroa mites. At the end of summer there was a sticky compensation for such support: We were able to collect more than eighty pounds of honey, though not without a valiant fight from the winged residents of the more territorial hive.

Andrea also participated in a robust, nationwide study on flying insects earlier this spring. A Malaise trap (what is essentially a vertical corral for flying insects) was set up in Crisp Field, a large meadow on Powdermill property, and throughout the summer my responsibilities included sorting everything collected in this trap. This exercise was a three-month affair. I conducted an up-close and personal survey of the sheer amount of diversity found in each order of insects, an experience mirrored by the periodic aquatic macroinvertebrate surveys we performed together along streams and ponds across the property.

From insects to reptiles to trees, each project I embarked on got me closer to truly understanding the world around us. In many ways, this meant seeing the consequences of climate change and human influence. Situations reveal themselves to be more dire than one could ever hope to understand by just reading about it. But there is hope, because understanding the world around us also means you can see just how much life worth protecting there is, if you just know how to look.

Rosie Spinola is an intern at Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center.

Related Content

An Intern’s Experience Studying the Ecosystem at Powdermill

Encounter with an Orb Weaver Spider: Is It Predator or Prey?

Tracking Migratory Flight in the Northeast

2023 Point Counts at Powdermill Avian Research Center

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Spinola, RosiePublication date: September 1, 2023