New to this series? Read The Bromacker Fossil Project Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, Part VII, and Part VIII.

The Dissorophoidea are a group of ancient amphibians that were common about 290 million years ago, when the animals fossilized in the Bromacker quarry were alive. The group consists of small to medium-sized water- and land-dwelling vertebrates (animals with backbones) that ate invertebrates (e.g., dragonflies, cockroaches, and millipedes) and vertebrates smaller than themselves. Most scientists agree that modern amphibians (frogs, salamanders, and the reclusive, worm-like, subterreanean caecilians) had their origins among the dissorophoids. Three disssorophoid species are currently known from the Bromacker quarry, and at least one and possibly two more are yet to be described. Two of the described species, Tambachia trogallas and Rotaryus gothae, are members of the dissorophoid subgroup Trematopidae, and the other, Georgenthalia clavinasica, is a member of the subgroup Amphibamiformes. All of them inhabited the terrestrial realm and most likely only returned to water to breed.

The first trematopid discovered in the Bromacker quarry was found by Thomas Martens in 1980, and it is represented by a poorly preserved skull and skeleton. Stuart Sumida, as lead author of the scientific paper presenting it, coined the name Tambachia trogallas. Tambachia refers to the Tambach Formation, the rock unit preserving the Bromacker fossils, which in turn is named after the nearby village of Tambach, which is now merged with the adjacent town Dietharz to become Tambach-Dietharz. “Trogallas” is from the Greek “trogo,” meaning munch or nibble, and “allas,” meaning sausage, in reference to all of the bratwurst consumed during Bromacker field seasons by the authors of the Tambachia publication (Stuart, Dave Berman, and Thomas). The state where the the quarry is located, Thuringia, is famous for its bratwurst and rightly so. A hot bratwurst for lunch was always welcomed when we experienced what Thomas called “Scandanavian summers,” which were cold and rainy. The then-Bürgermeister (mayor) of Tambach-Dietharz, who also was a butcher, was so thrilled by the name that he hosted an annual bratwurst lunch featuring brats that he’d made. This tradition was carried on by subsequent Bürgermeisters, though they had to buy the featured main course.

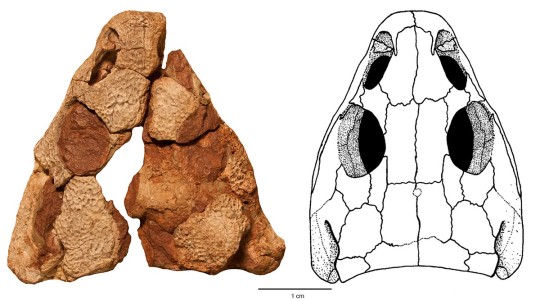

When Rotaryus gothae was found in 1998, only part of the skull was exposed, so we took out a large block expecting a complete skeleton to be preserved, as typically occurs at the Bromacker. Once I began preparing the specimen, however, I was extremely disappointed to find that only a small portion of the body of the animal was present. At least we had the skull, the most scientifically important part of the skeleton. Dave led the scientific study of Rotaryus, and he named it in honor of the Gotha Rotary Club, an organization that generously provided financial support for Bromacker fieldwork. Dave sent the head of the Gotha Rotary Club three choices for the fossil’s name, and the members voted on which one to use.

At the time that Tambachia and Rotaryus were named and described in scientific publications in 1998 and 2011, respectively, trematopids were known only from the USA. Their presence at the Bromacker added to the growing list of animals previously thought to only inhabit North America, such as Diadectes and Seymouria. In hindsight, it is not surprising that trematopids also had a more cosmopolitan distribution, because although they are amphibians, their skeletons were strong enough to support their body out of water and withstand the effects of gravity, thus enabling them to disperse to far corners of the world (though hypotheses of such dispersal assume that no physical or climatic barriers prevented movement).

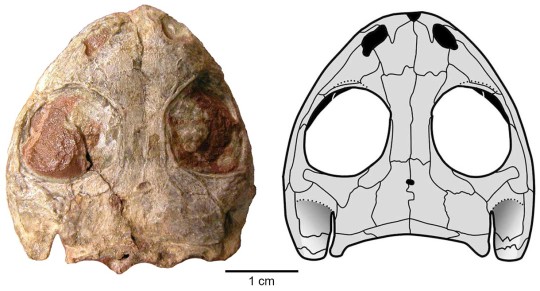

I was the lucky person who discovered, in 2002, the amphibamiform Georgenthalia clavinasica. I recall lifting up a block of rock that I had loosened with a hammer and chisel and seeing two ghostly eye openings staring back at me. The rest of the skeleton was preserved with the skull, but unfortunately all bone beyond the skull was extremely eroded from groundwater and had the consistency of mashed potatoes.

After Tambachia was named, the Bürgermeister of the nearby village of Georgenthal, whose boundaries included the Bromacker quarry, approached Dave about naming a fossil after his village. Dave then asked Jason Anderson, a colleague from the University of Calgary and the project’s lead researcher, to name it Georgenthalia. Jason created clavinasica from the Latin “clavis” for key, and “nasica” for nostril, in reference to the fossil’s keyhole-shaped nostril, a unique feature that differentiates Georgenthalia from all other amphibamiforms.

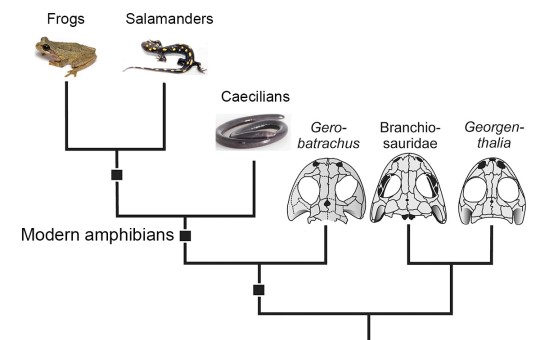

Jason, as lead author of a 2008 scientific publication, concluded that the relationship of Georgenthalia to other amphibamiforms was uncertain. Computer algorithms are used to analyze relationships of organisms by tabulating the proportion of unique characteristics shared between the members of the group under study. A group of organisms that share unique characters is called a clade, and members of a clade are considered to be more closely related to each other than they are to members of other clades. These relationships are depicted in a diagram of relatedness called a cladogram.

A 2019 study by dissorophoid expert Rainer Schoch (Curator, Naturkunde Museum Stuttgart) that investigated the ancestry of modern amphibians revealed Georganthalia as a member of a clade that also includes modern amphibians (see figure below). The fossil Gerobatrachus, however, is more closely related to modern amphibians than it is to the clade consisting of Georgenthalia and Branchiosauridae (a group of aquatic amphibamiforms). This indicates that although Georgenthalia (along with Branchiosauridae) is in the clade containing modern amphibians, it is not directly ancestral to them.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature yet another terrestrial amphibian, a fossil from a locality in Tambach-Dietharz.

If you would like to learn more about Tambachia, Rotaryus, or Georgenthalia, please follow the links below.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Keep Reading

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part X: Tambaroter carrolli, an Amphibian with a Wedge-Shaped Head