White-tailed deer overbrowsing

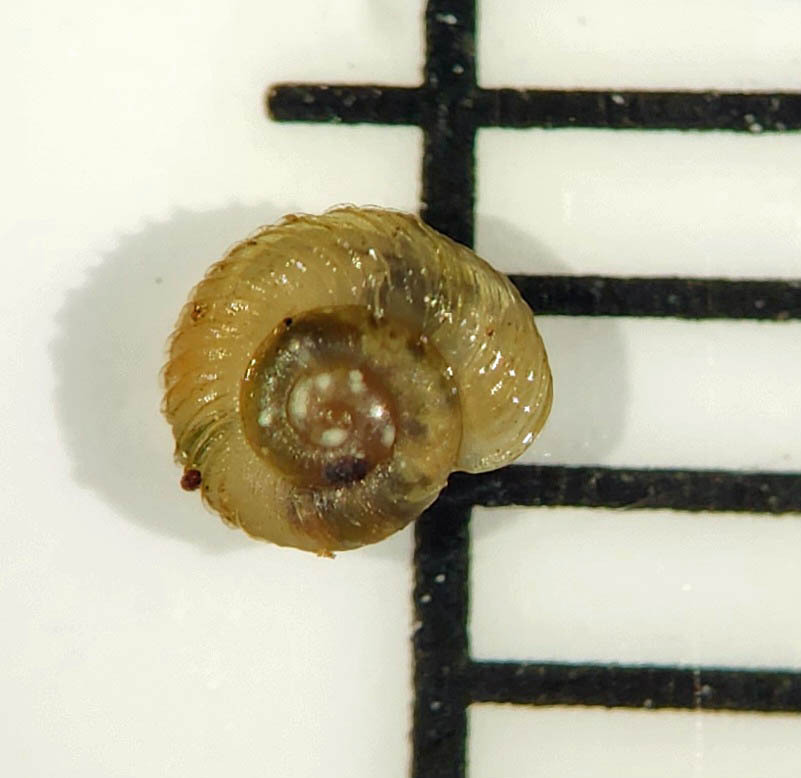

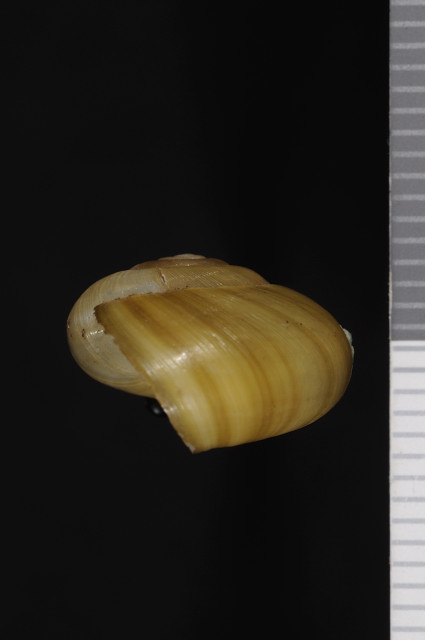

Land snails are likely to be impacted by white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) overbrowsing, but empirical evidence is lacking.

Typical evidence of white-tailed deer overbrowsing is widespread in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources discusses the reduction of forest tree regeneration and other deer overbrowsing impacts upon vegetation and wildlife in their report on the state’s forests (2005). Lack of advance regeneration of many tree species is widespread. Other overbrowsing indications include the “browse line” of reduced foliage on the lower parts of trees and shrubs, reduced herbaceous vegetation, and understories dominated by hay-scented fern, striped maple, and other plants unpalatable to deer. In addition, other vegetation impacts from air pollution and non-native invasive plants such as Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) impede forest recovery from deer overbrowsing. Adding complexity to this topic are deer parasites that have land snails as a secondary host, an issue addressed in another “Ecology” subsection on this website.

White-tailed deer overbrowsing impacts upon ground-nesting birds have been documented (e.g. deCalesta, 1994), although the extent to which overbrowsing limits other wildlife including invertebrates is mostly unknown. White-tailed deer are Cervids, the even-toed herbivores, and browsing impacts upon land snails from the Cervids moose (Alces alces) and caribou (Rangifer tarandus) have been reported in Scandinavia (Suominen, 1999;Suominen et al., 1999). In a New Zealand study of several invertebrate taxa, introduced goats and deer impacted larger-bodied invertebrates (Wardle et al., 2001). Although the extent of the impact to land snails due to white-tailed deer overbrowsing in eastern North America is unknown, we can presume at least some effect because of the obvious reduction of land snail food and cover. Research into this effect could be useful to land managers and conservationists.

In light of the potential for overbrowsing effects, wildlife management practices that serve to increase deer near special land snail habitats or rare land snail locations should be of particular concern. Practices at issue would include vegetation management, specifically road building, timber harvest, and creation and maintenance of wildlife openings. Research into creating adequate habitat buffer zones and limiting white-tailed deer numbers to allow understory recovery are needed. New research could provide a contribution to the discussion about improving white-tailed deer management policy.