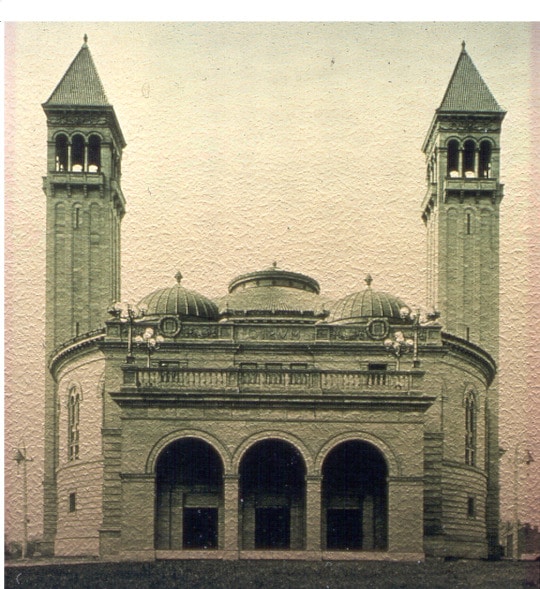

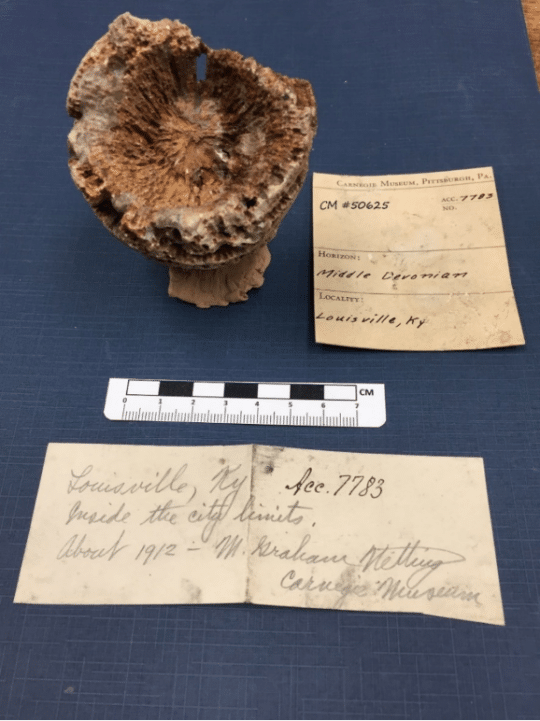

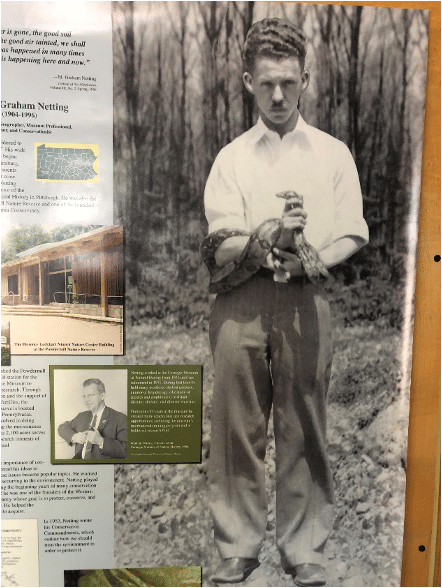

In 1912, eight-year-old M. Graham Netting unearthed 13 coral fossils within the city limits of Louisville, Kentucky. Later, as a 22-year-old Pitt student, he donated them to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Figure 1). When the Great Depression cut short his graduate studies at the University of Michigan in 1929, he returned to the museum as Assistant Curator of Herpetology, and worked his way up to Curator in 1932. In 1954, six months before turning 50, he was appointed Director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Along the way, the Wilkinsburg native left an astonishing legacy that includes a steady growth in scientific collections, numerous wildlife dioramas in the Halls of Wildlife, and a mid-Appalachian field research station, Powdermill Nature Reserve. Upon his retirement in 1975, the Post-Gazette noted, “Long before it was “in,” Netting saw pollution of the air and water ravaging the land.”

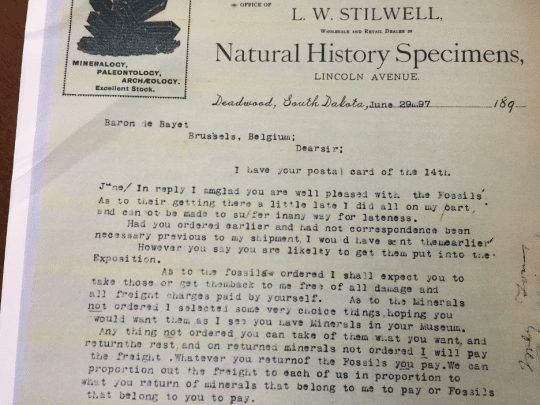

Albert Kollar, Collection Manager of the of Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, re-discovered young Graham Netting’s horn corals while working on a multiyear review of the Bayet Collection. Netting’s label note did not provide any evidence for the stratigraphic unit that he collected from, but more on that later.

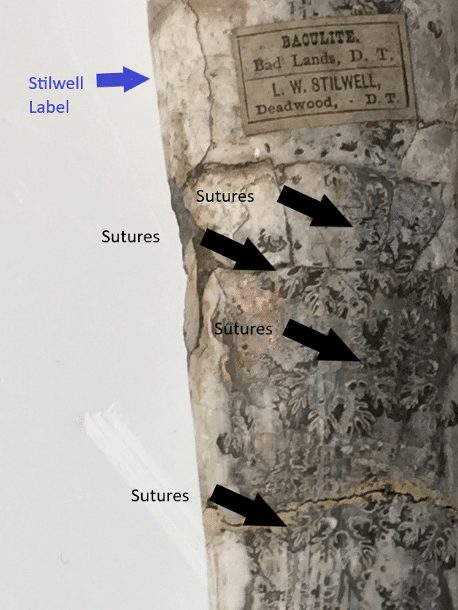

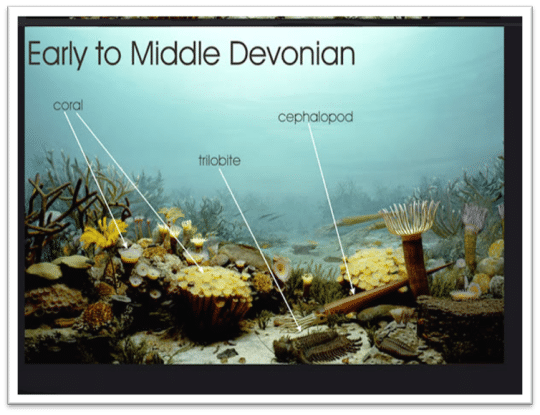

Rugose corals are often called horn corals because many species have a horn shape. Horn corals attach to the sea floor by way of a sticky tentacle that protrudes from the base or curved end of the animal. Other invertebrate animals, such as brachiopods, attached in this position are described as sessile. The coral animal or “polyp” built its skeleton from calcium carbonate, a mineral formed from Bicarbonate and Calcium ions in seawater. The polyp tentacles or feeding polyp extend out from the top of the basic body for feeding (Figure 2). When the animal died, its soft tissues would have decayed and left behind the external hard mineral skeleton that fossilized.

Netting’s Louisville coral specimens are fossilized in a different way than similar corals from the nearby Falls of the Ohio middle Devonian fossil beds. His corals are lighter and fragile to the touch, conditions which gave Albert reason to compare Netting’s fossils to similar invertebrate paleontology corals from strata within the Louisville area. Sometime during or after burial, these horn coral skeletons were replaced by silica or quartz, a process known as silicification. The mineral silica can saturate a column of seawater when the seabed is overwhelmed with a large population of sponges. Sponge skeletons are composed of silica and when they die silica is added to a column or more of seawater. Volcanic eruptions eject silica into the atmosphere that eventually settles into the sea. Again potentially adding higher amounts of silica. Whatever the cause, Albert believes Netting’s corals were collected from the fossiliferous Middle Devonian age Jeffersonville Limestone, where the “lower foot of a “conglomerate” of reworked silicified Louisville Limestone” of Upper Silurian age is known to occur with silicified coral fossils (Conkin and Conkin, 1972).

Horn and Tabulate corals thrived in shallow seas forming diversified ecological reefs from about the late Silurian Period to the beginning of the Late Devonian epoch. During the Middle Devonian epoch roughly 400 Ma to 390 Ma years ago, reefs formed in central New York, southern Ontario, central Ohio, central Iowa, western Alberta, Canada, western Australia, and in Eifel, Germany.

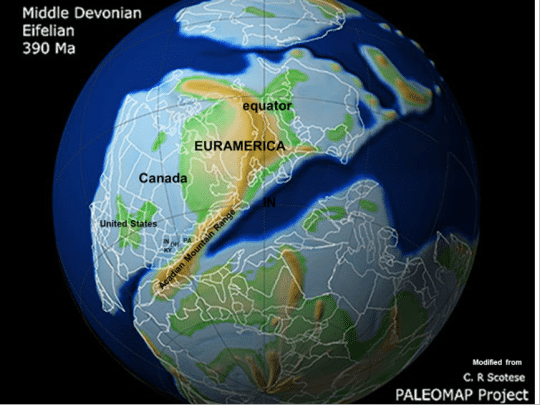

Louisville, during the Devonian Period, was centered in the southern hemisphere about 40 degrees south of the equator. Because of plate tectonics, the coral beds of Louisville would travel 5,500 miles over the next 390 million years to their present-day location of 38 degrees north (Figure 3). Today, fossil outcrops in the city limits of Louisville are difficult to find.

When Netting retired as Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, he moved to a modest house next to Powdermill Nature Reserve. A seat was saved for him each Sunday at the reserve’s weekly nature talk. In 1996, he passed away. Steve Rogers, Collections Manager for the Section of Birds, recalls sipping fresh lemonade on Netting’s back porch in 1981. According to Rogers, Netting was reflective and humble. The fossil collector who became a museum director had a habit of rubbing his chin while listening to someone speak. When asked about his legacy, Rogers replied, “He was more instrumental in forming Powdermill than anyone. He had an amazing ability to be a part of a team that got things done.”

As Netting prepared to step down as director in 1975, he said, “These great collections are a natural resource to answer questions about the life of the world.” On a recent day, I saw two children jumping up and down in front of the Glacier Bear diorama in Hall of North American Wildlife on a family visit to the museum. When one of the children asked, “what’s a diorama?” I thought about Graham Netting, smiled, and encouraged their engagement with the life of the world.

Many thanks to Xianghua Sun, Carnegie Museum Library Manager, Marie Corrado, Carnegie Museum Library Clerk, Stephen Rogers, Collections Manager for the Section of Birds, and John Wenzel, Director of Powdermill Nature Reserve for help researching this post.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.