New to this series? Read The Bromacker Fossil Project Part 1 here.

Finding fossils at the Bromacker quarry was tedious and physically demanding, but it was extremely rewarding when a fossil is discovered. Our annual summer field season generally lasted three and a half weeks. Because the weather usually wasn’t conducive to camping or cooking outdoors, we stayed at the same hotel and dined at the hotel or local restaurants.

The original 1993 fossil quarry was opened using heavy equipment and operators from the nearby commercial quarry, and in the early years we relied on these people to expand the fossil quarry’s boundaries as needed. When the commercial quarry was temporarily shut down due to the lack of contracts for building stone, our collaborator Dr. Thomas Martens fortunately was able to obtain funding to annually rent a Bobcat, which he became skilled at operating. Thereafter, Thomas would use the Bobcat to expand the quarry and remove soil and weathered rock layers, so that we could begin our yearly excavation on unweathered rock.

We would each stake out an area of the quarry to work in and then proceed to work through the rock layers by using a hammer and chisel or pry bar to free a piece of rock. Its surfaces and edges would be checked for fossil bone, and if there was none, the rock piece would be broken into smaller pieces, which were also checked for bone. As is the case at many other fossil sites, the rock tended to split along the plane a fossil was preserved in, because the fossil would create a zone of weakness.

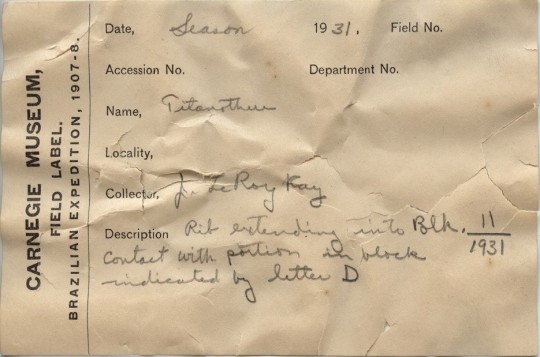

Once a fossil specimen was discovered—and there were a few frustrating years when this didn’t happen—the hard work of extracting it from the quarry began. Here, I’ll use a fossil discovered during the 2006 field season as an example of how this was done.

First, we would isolate the fossil specimen from the surrounding rock, exposing as little of the fossil as possible while determining its extent, because it would have been easy to lose pieces of bone in the dirt and mud. Then we would encase the specimen in a plaster and burlap jacket to protect it during extraction, shipping, and preparation.

To make the jacket, we’d coat cut strips of burlap in wet plaster and then spread them across the surfaces of the rock containing the specimen, or block. A layer of plastic (plastic bags worked well) was applied to the top surface of the block to keep plaster from sticking to any exposed bone.

After a couple layers of plaster bandages were applied to the top and sides of the block, the block was undercut, with plaster bandages added periodically to hold the undercut rock in place.

When deemed safe, we would crack the block free from the quarry floor using hammers and chisels, and flip it over, unless it broke free on its own. Excess rock would be removed from the bottom of the block to make it lighter in weight. Then we would apply burlap and plaster bandages to the bottom of the block. The block would be removed from the quarry and stored at the MNG until it was shipped to Pittsburgh.

We encountered several problems during our quarry operations over the years. As we worked our way through the rock column in the quarry, processed rock piled up on the quarry floor. In the early years, we tossed or shoveled the processed rock into wheelbarrows and pushed the heavy, unwieldy wheelbarrows out of the quarry to a dump pile. Fortunately, the Bobcat eventually replaced the wheelbarrows for moving processed rock. As we ran out of space outside the quarry to dump processed rock, the rock was used to backfill older portions of the quarry.

Another problem was that fossils found at the bottom of the quarry were often extremely difficult to undercut because the rock so was hard. Sometimes a well-hit chisel would just bounce off the rock instead of cracking or penetrating it. One year we had to resort to a rock saw to undercut a block.

Rain was always a problem. We would shelter in our cars during intervals of rain, or work at the museum if the rain was heavy and persistent. Occasionally heavy rain would flood the quarry, forcing us to work in the ‘dry’ areas of the quarry while a pump drained the water. Of course, we had contests to see who could skip a rock the farthest or make the biggest splash.

Next week’s post will describe the process of fossil preparation, that is, removing rock to reveal a specimen in the lab. The fossil collected in the 2006 field season will be used as an example.

Here are some videos taken by taken by Thomas Martens’ wife, Steffi, during the 1993 and 2006 field seasons. These show the process of searching for fossils (1993 video) and collecting the fossil highlighted in this post (2006 videos).

Bromacker Quarry 1993

Bromacker Quarry 2006

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.