by Annie Lindsay

During the 2024 calendar year, we operated Powdermill Avian Research Center’s (PARC) bird banding station for 184 days across all four seasons, during which we banded 9,415 new birds, processed 4,581 recaptured individuals, and released 9 birds unbanded. These 14,005 birds represented 125 species, one of which was new to Powdermill’s banding dataset.

The banding station at PARC has been running year-round since June 1961 and has accumulated over 850,000 banding records of nearly 200 species, so a new species for the station is a relatively rare event. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves and spoil the surprise, which happened near the end of 2024.

At Powdermill, we band birds year-round, which is somewhat unique among banding stations. We increase our effort during the spring and fall migration seasons and band fewer days each week during the breeding season and winter. This helps us track seasonal events like arrival and departure timing of migratory species, onset of breeding activities, relative abundance of different species, site fidelity (whether individuals come back to the same breeding or wintering areas every year), and longevity. Banding year round also allows us to observe the seasonal progression of birds from familiar to fancy and back again.

Each year, there are species or events that cause excitement among the banding crew. Some of them might be species that are uncommonly caught at Powdermill or difficult to see in the wild, some might be individuals that are earlier or later in the season than expected, some might be favorite species that we never tire of seeing, and some might be days with unusually high capture rates or big days. As each year comes to a close, we reflect on the highlights and compile a list of our favorite moments, of which 2024 had an abundance.

The first highlight of 2024 was a Red-shouldered Hawk that we caught and banded on January 24. A species that is a little too big for our songbird-size mist nets, raptors and other large birds generally bounce right out of the nets. This bird was holding on to a trammel line with its talons which gave the bander a split-second advantage. A species that seems to be expanding its range northward, Red-shouldereds can be found in southwest Pennsylvania year-round, although this is only the 6th ever banded at Powdermill.

As winter waned and we prepared for the spring migration season, we caught an unexpectedly early Gray Catbird on March 27, setting a record for the earliest catbird banded at Powdermill (the previous earliest banding record was on April 19). Spring progressed relatively normally until May 9 when we caught Powdermill’s ninth ever Swainson’s Warbler. This is a species that has historically bred in the southeastern part of the US but was confirmed as a breeding species in Pennsylvania (at Bear Run Nature Reserve just 30 minutes south of Powdermill) for the first time in the summer of 2023. These breeding records may represent a northward range shift for this species.

The spring migration banding season ends at Powdermill at the end of May, but we continue to band, with reduced effort, through the summer. On June 7, we caught a Tennessee Warbler, a species that migrates annually between breeding sites across much of Canada and wintering grounds in the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America. They are commonly found at Powdermill during the migration seasons when they stop over to rest and refuel between flights. Nearly all Tennessee Warblers have moved north of us by the end of May, making our June 7 capture the second latest spring record for this species in our dataset. There was something a bit unusual about this individual: it was molting feathers that suggested that it was undergoing the post-breeding molt, something that happens before, or sometimes during, the early stages of fall migration. Although there wasn’t time for this bird to have attempted breeding, perhaps something caused this individual to turn around and head south, representing the earliest (by more than a month!) fall migrant Tennessee Warbler in our dataset.

Summer progressed relatively normally, but the lack of rain began to become noticeable as streams became trickles and small ponds dried up. By July each year, we begin to catch birds in their post-fledging period and our capture numbers increase, but we were not expecting to have one of the biggest summer banding days in our 63-year history when we caught 153 birds on July 17. For context, we were operating about 1/3 of the nets that we run during migration and had to close the nets early due to heat, so the 153-bird day was quite impressive and our third highest summer banding total. This was the beginning of a severe drought that gripped our region through much of the second half of the year, and the ponds near PARC held some of the only locally available drinking water for breeding and migrating birds. We suspect this concentrated birds in the banding area and increased capture rate in late summer and throughout fall.

The fall migration banding season begins in August as the current year’s fledglings begin to disperse and the first migrants begin to move south. Following the trend of a higher-than-usual concentration of birds in the banding area, we had several species with above average captures and two that broke the single-day high totals. On August 16, we caught 11 Blackburnian Warblers and on September 3 we caught 35 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Both species breed locally, but we catch the majority of individuals during the post-breeding and fall migration season.

The second half of September and the first half of October is the busiest part of the banding year, and interesting captures came in rapid succession during that period in 2024. Soras are a species of rail, a secretive marsh bird that is usually difficult to see, and that we average fewer than one capture per year. We caught a Sora on September 21 and a second one on September 24 – these were #22 and #23 in our dataset, and only once before did we catch two in one season.

September 24 held the banding crew’s biggest highlight of the year: a Kirtland’s Warbler. Kirtland’s Warblers are one of the rarest species of wood warblers in North America – it was critically endangered with a population of about 167 pairs in the 1970s-80s. It is an Endangered Species Act success story: with habitat management and control of brood parasites, the species recovered to a healthy population of ~4,500-5,000 birds and was delisted in 2019. Although it’s not an abundant species, given its migratory route between breeding grounds in Michigan and wintering grounds in the Bahamas, we knew it was just a matter of time before one was spotted in southwest Pennsylvania. Remarkably, this was not the first Kirtland’s Warbler caught at Powdermill: one was banded on September 21, 1971 when the population was at its low point.

Over the years, a few possible Bicknell’s Thrushes were banded at Powdermill, but it wasn’t until 2023 that two were definitively identified here. They’re difficult to identify because they look very similar to Gray-cheeked Thrush, but average a bit smaller and more reddish in color. On September 27, we caught and banded another, this one noticeably reddish and falling well within Bicknell’s measurements. Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s Thrushes were considered the same species until 1995, when there was enough evidence (based on morphology, vocalizations, habitat, and migration patterns) to elevate Bicknell’s Thrush to full species status.

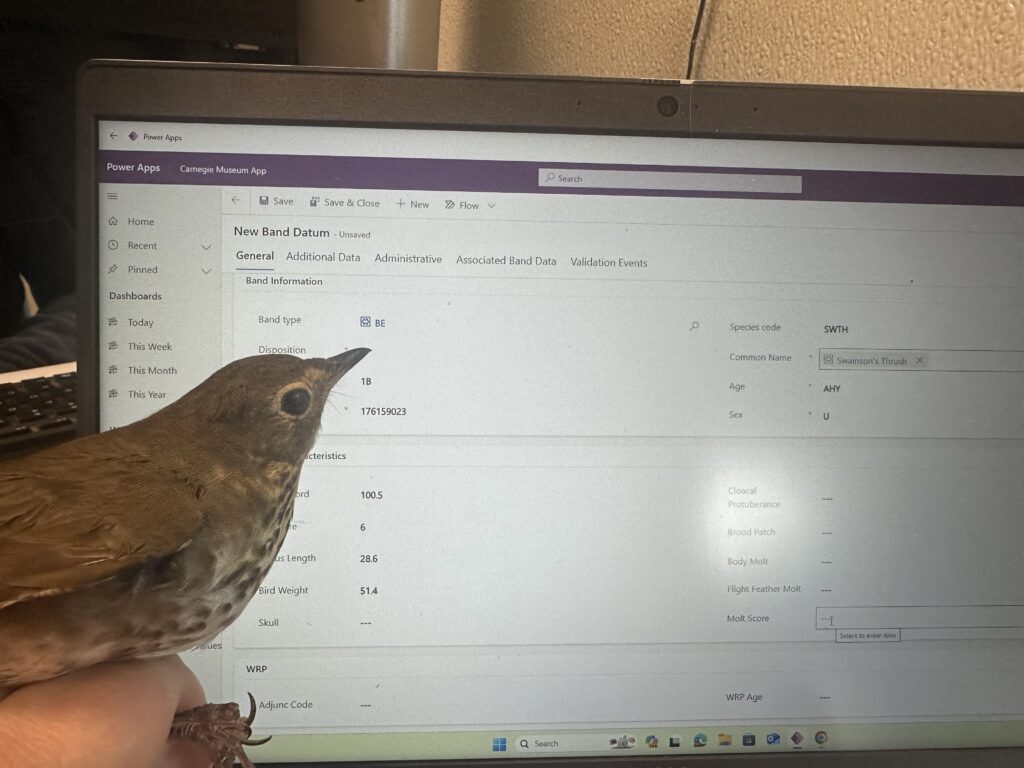

Fall migration would not be complete without a fat bird highlight. During the migration seasons, migratory songbirds increase their food intake so that they can deposit fat reserves that they use as a source of energy to fuel their overnight flights. Songbirds flap their wings continuously while they fly, so they require a lot of energy to accomplish their migrations. A Swainson’s Thrush that we caught on September 27 had accumulated impressive fat deposits, weighing in at 51.4 grams. Powdermill’s dataset contains over 17,000 Swainson’s Thrushes and only three have been heavier than this bird. A fat bird is a bird that is well prepared for migration!

Old birds are interesting captures, and a Wilson’s Snipe that we caught on October 11 was just that. This individual was banded in 2019 and aged as a bird that hatched at least in 2017, if not earlier. Not only is this a notably old bird, but it had been recaptured three other times at Powdermill, providing us a peek into its life.

The fall migration banding season began to wane as October progressed, and our seasonal field techs’ last day was November 2. But the surprises hadn’t stopped yet! In the morning, we caught an unusual Empidonax flycatcher (Empidonax is the genus of flycatchers that tend to pose identification challenges) – it was quite yellow on its underparts and the face proportions were not quite right for any of the species expected in the east. Further, an Empidonax flycatcher in southwest Pennsylvania this late in the year would be exceptionally rare. After a series of diagnostic measurements done independently by three of the banders on staff, we determined that this individual was a Western Flycatcher, a species found in the western part of the continent from the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Coast, and a species never before banded at Powdermill.

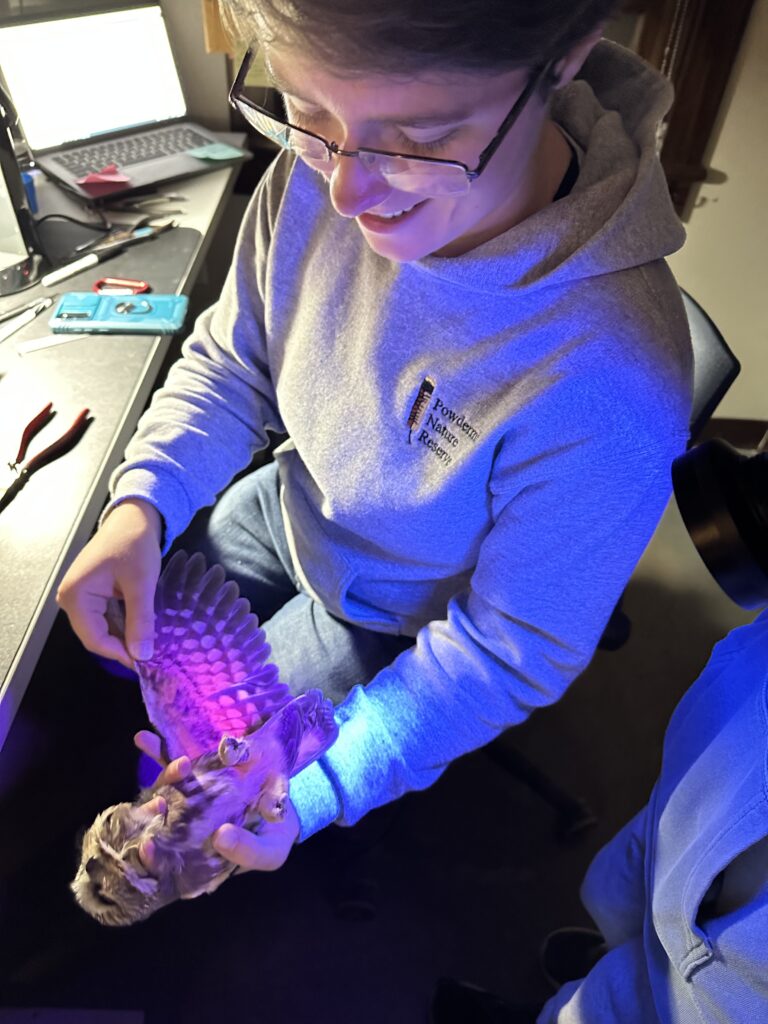

Later that evening, we set up nets to catch owls for Powdermill’s public Owling at the Moon event. Using audio lures, we attempted to catch Northern Saw-whet Owls and Eastern Screech-Owls. Successfully catching owls is very weather-dependent, and luck was on our side this year. Not only did we catch several individuals of our two target species, but we had a big surprise when we caught a Barred Owl, the second ever caught at Powdermill. The crew was excited to get to study this species in the hand and to share it with Owling at the Moon attendees.

It was a busy but satisfying year, full of visitors and events, bird banding workshops, and interesting birds, and we look forward to what 2025 will bring!

Annie Lindsay is the Bird Banding Program Manager at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the environmental research center of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Read More Science Stories

(De)Forested Flight: An Eagle Scout Project at Powdermill