by Annie Lindsay

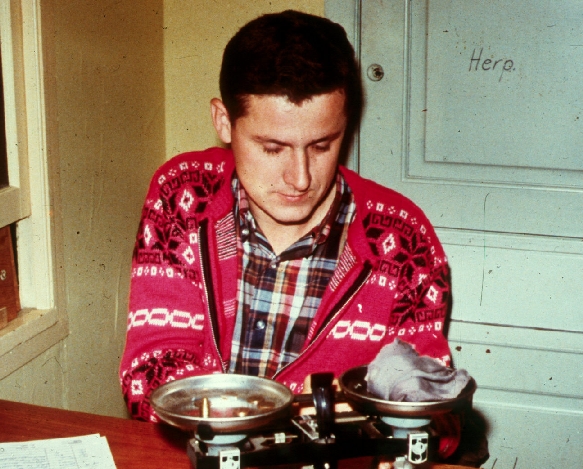

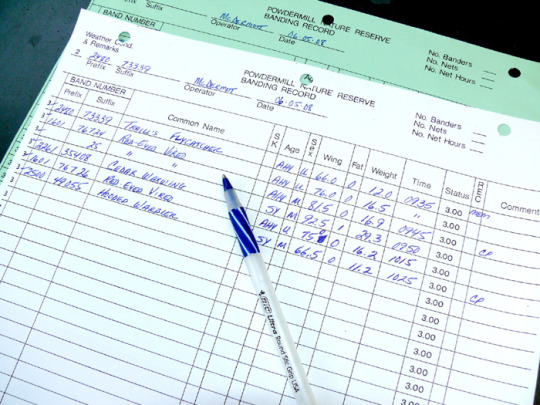

Nestled between the Chestnut and Laurel Ridges near the town of Rector, Pennsylvania lies Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental field research station, where ornithologists have been operating a long-term bird banding station since June 1961. In 62 years of banding birds year-round, we’ve gathered more than 830,000 banding records of nearly 200 species. Some, like the Cedar Waxwing, have tens of thousands of records in our dataset, whereas single individuals are the only representatives of other species, like Kirtland’s Warbler.

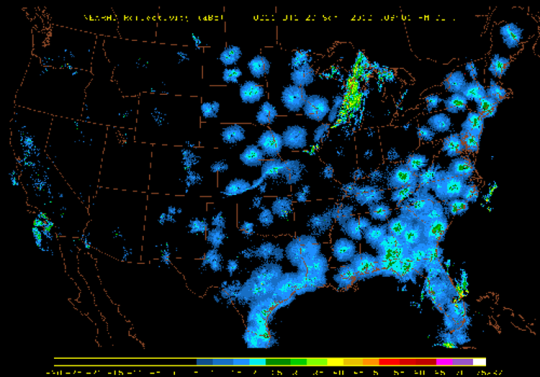

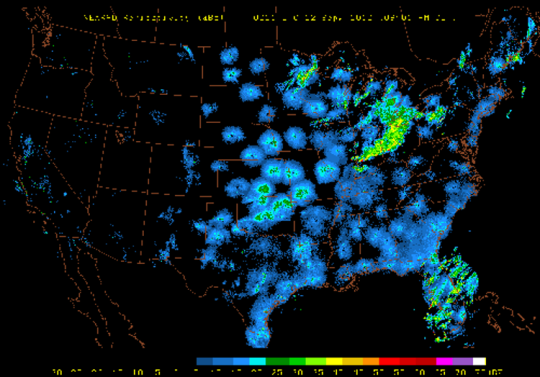

At Powdermill, we band birds all year, varying our effort seasonally, which gives us a picture of what species we expect to see at any given time of year and the relative abundance of those species. Each season brings something new. By March we are eagerly awaiting the earliest spring migrants and as spring progresses, we revel in the flood of colorful songbirds in their breeding plumage. Summer brings breeding birds and our anticipation of which individuals will return year after year. As summer fades into fall, we enjoy the subtle beauty of birds in their non-breeding plumage as they migrate south to their wintering grounds. By mid-November, almost all migrating songbirds have passed through and we are in our winter banding season, dominated by cold-hardy birds that are often recaptured between years.

In 2023, we banded 9,095 new birds and recaptured 5,074 individuals of 123 species (plus one hybrid). The most abundant species was Swainson’s Thrush with 631 new birds banded this year, followed by Ruby-crowned Kinglet (596), Gray Catbird (484), and Cedar Waxwing (447). The year saw slightly lower numbers than average overall, but several species had notably high captures and some even set spring or fall season records. In spring, 11 Black-billed Cuckoos edged out last year’s ten to claim that season’s record, and in the fall nine Louisiana Waterthrushes (a species that is a very early migrant and generally scarce during our fall months), 158 Ovenbirds, and two Bicknell’s Thrushes set fall high records.

We can use these numbers to compare 2023 to previous years and to totals from other banding stations, but the stories about the year’s highlights are most compelling. Each year when we analyze our data, we eagerly look for species that set new record high totals, individuals that represent early or late banding dates, or recaptures that are particularly old birds, and await reports that our banded birds have been recaptured at another station.

This year, as in recent years, many of the species that had above average totals are species that have been increasing in southwestern Pennsylvania, which is a trend that is reflected in Christmas Bird Count data. The core of these species’ ranges has historically been a bit farther south, but they seem to have recently been expanding northward. For example, Carolina Wrens and Red-bellied Woodpeckers are year-round residents in southwestern Pennsylvania and are encountered far more often now than they were a few decades ago. Similarly, Yellow-throated Warbler is a species that tends not to breed much farther north than non-Appalachian Pennsylvania, but is a species that we’ve seen in spring attempting to establish territories and even breeding.

This year’s exciting captures began with a Swainson’s Warbler that was caught on May 11, only the eighth individual of that species in Powdermill’s banding dataset. Swainson’s Warblers breed significantly south of Pennsylvania in the very southern part of West Virginia, but since 2020, birders have spotted several nearby in the spring and summer and the first breeding record in the state was confirmed in summer 2023. This unexpected capture, affectionately nicknamed “Sword-billed Warbler” by the banding crew, was certainly a favorite.

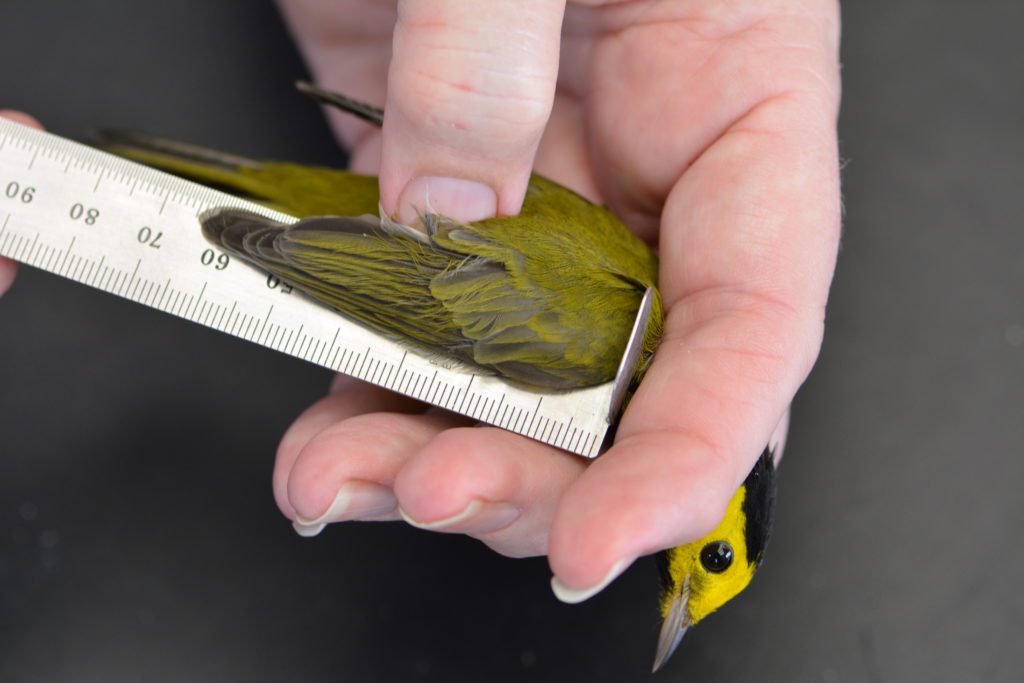

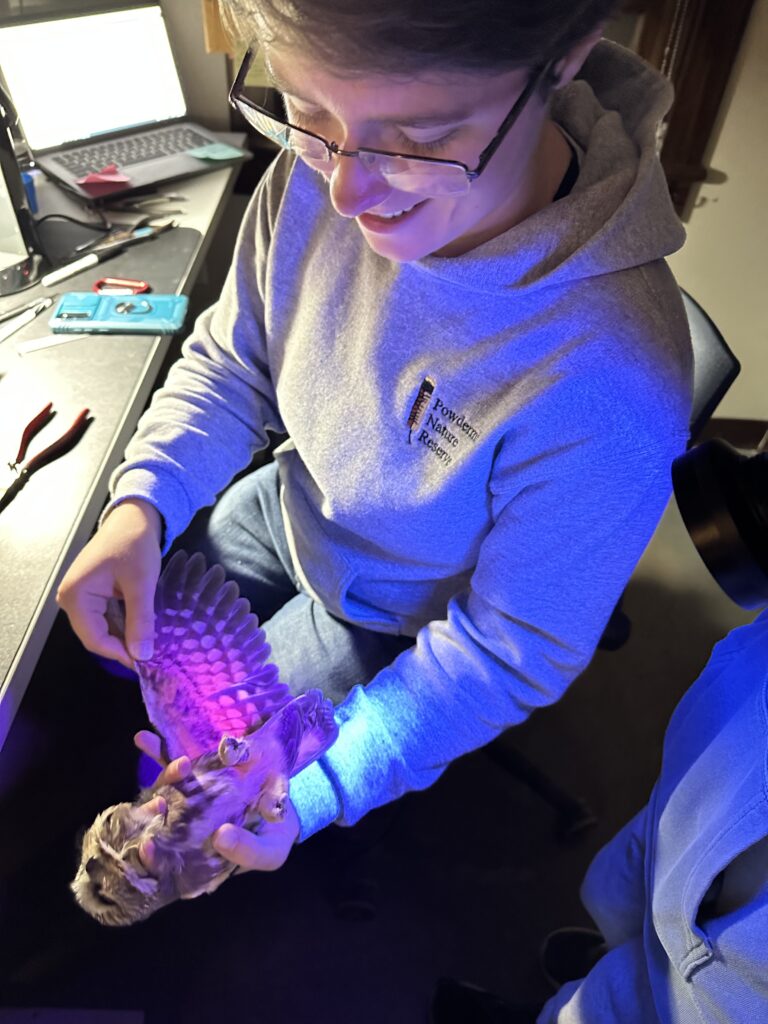

This fall, something happened that is rare for a 62-year-old banding station: we added a new species to our dataset. Bicknell’s Thrush was considered a subspecies of the more common Gray-cheeked Thrush until 1995 when there was enough evidence (based on morphology, vocalizations, habitat, and migration patterns) to elevate Bicknell’s to full species status. Over the years, a few possible Bicknell’s Thrushes were banded at Powdermill, but it wasn’t until this year that two were definitively identified here, one on September 14 and one on October 8.

One of the questions we are frequently asked is how long birds live. While it’s difficult to know how long each species lives on average, recapturing birds between seasons tells us something about how long they can live. In general, smaller birds are shorter-lived and larger birds are longer-lived. Catching a bird with a band and looking back through the data to see how long ago it was initially banded and how many times it’s been captured over the years is a highlight for the banding crew. Several notable standouts in 2023 include:

- A Ruby-throated Hummingbird that was banded in August 2021 and aged as a bird that had hatched in a previous year was recaptured exactly two years later, making her at least three years old.

- A Kentucky Warbler that was banded in June 2018 and aged as a bird that had hatched the previous summer was recaptured in May, making it six years old.

- A Gray Catbird that was banded in August 2015, the summer it hatched, was recaptured this fall when it had a refeathering brood patch (the bare patch of skin on the belly that songbirds develop to help incubate eggs). This catbird was eight years old and, because female catbirds develop brood patches when they’re breeding, we were able to determine that she was breeding at Powdermill that summer.

- Black-capped Chickadees are frequently recaptured because they’re year-round residents at Powdermill and because they tend to spend time at feeders near the banding station. Because of this, we often have their band numbers memorized and sometimes can recognize individual mannerisms. This fall, we caught one such chickadee several times; it was banded in April 2016 and aged as a bird that had hatched the previous summer, making it eight years old!

There were many more old birds captured in 2023, each one delighting the crew with its history.

PARC is back to the winter banding schedule and we’re looking forward to what 2024 will bring us!

To learn more about bird banding, please see the post “What is bird banding?”

Annie Lindsay is the Banding Program Manager at Powdermill Nature Reserve.

Related Content

2023 Rector Christmas Bird Count Results

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Lindsay, AnniePublication date: February 8, 2024