by Patrick McShea

“Tell me what gives you hope?” The student’s question during a high school environmental science class in March left me scrambling to deliver a clear and honest answer. “Tell me,” she added for emphasis, “because I really want to know.”

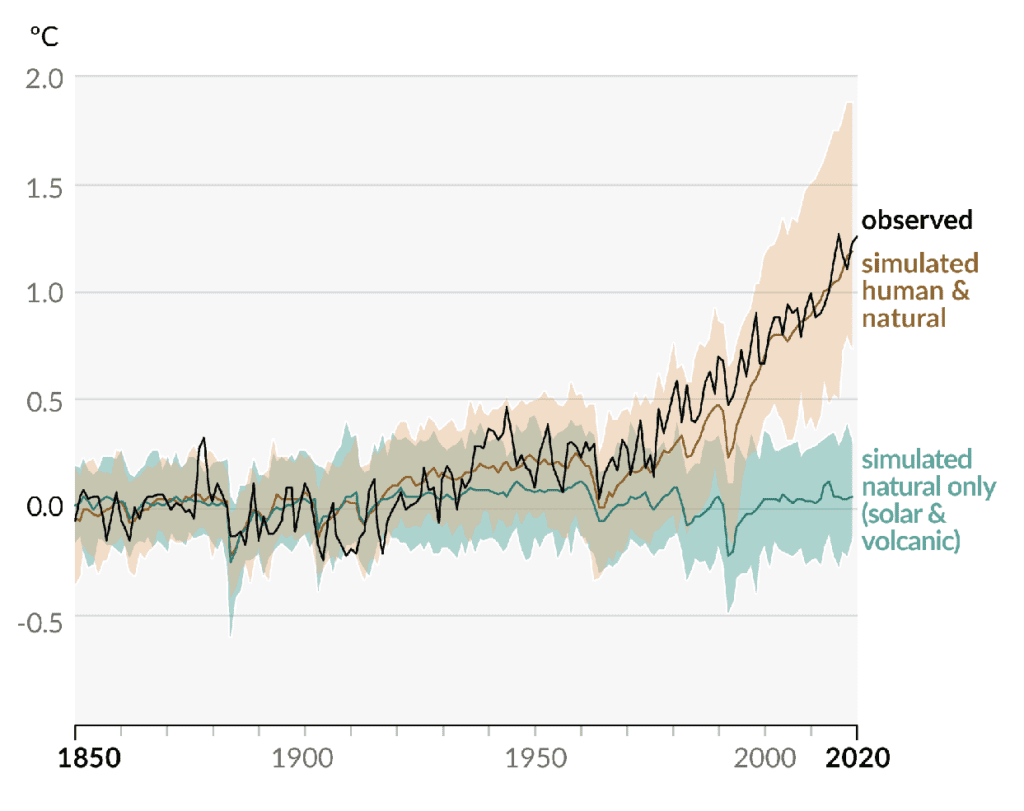

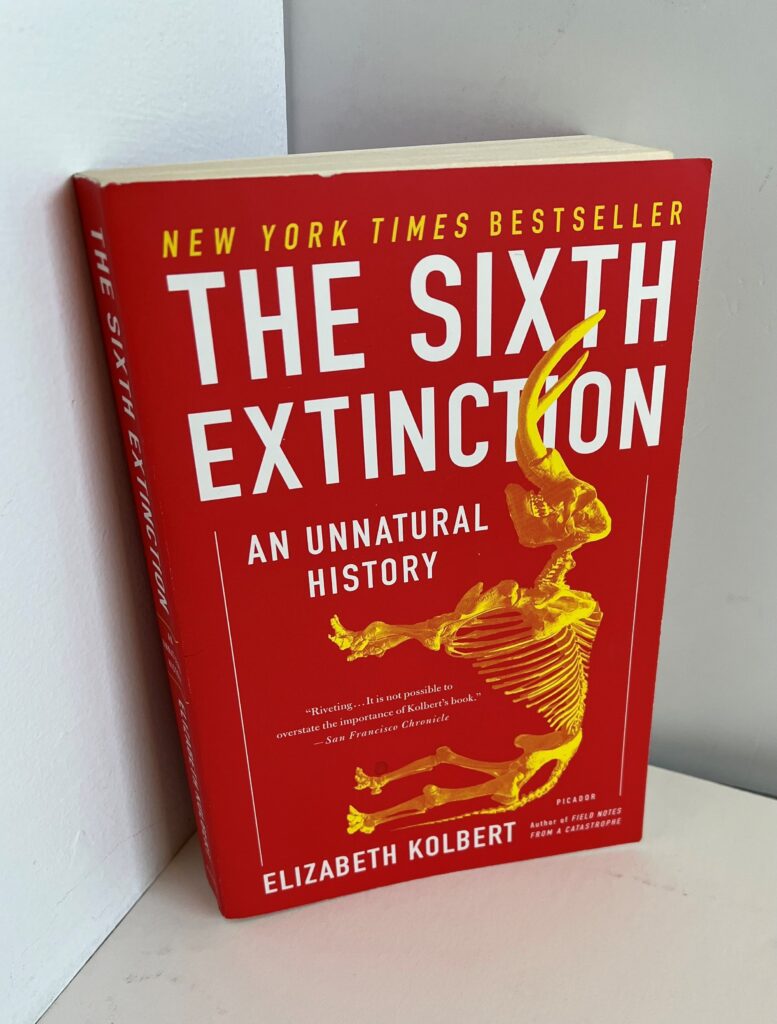

Ten students had just listened to me explain the cascade of negative effects associated with the increasing acidification of ocean waters. The frightful phenomenon is on a scale proportional to and correlated with the climate altering changes in Earth’s atmosphere. My presentation was a summary of a single chapter in The Sixth Extinction, science writer Elizabeth Kolbert’s landmark 2014 book exploring warning signs of a coming human-induced extinction event as destructive as the five previous episodes documented in the fossil record.

In “The Sea Around Us,” a chapter whose title pays homage Rachel Carson’s best-selling 1951 book by that name, Kolbert frames her ocean report with an explanation of a vital large-scale chemical interaction:

Ocean covers seventy percent of the earth’s surface, and everywhere that water and air come into contact there’s an exchange. Gases from the atmosphere get absorbed by the ocean and gases dissolved in the ocean are released into the atmosphere. When the two are in equilibrium, roughly the same quantities are being dissolved as are being released. Change the atmosphere’s composition, as we have done, and the exchange becomes lopsided: more carbon dioxide enters the water than comes back out.

Much of the chapter consists of Kolbert’s account of her visit with scientists studying marine life in a bay of the Tyrrhenian Sea where water chemistry has long been impacted by carbon dioxide-rich discharges from submerged volcanic vents. The narrative helped the students understand how researchers use models to make predictions, and that ecological models are not always computer simulations. In a summary of acidification impacts in the study area, Kolbert notes limpet shells bearing “deep lesions through which their owner’s putty-colored bodies can be seen.” Perhaps my sharing of this type of graphic detail spurred the student’s urgent question about hope.

My answer, which lacked quotable coherence, involved trees. Speaking directly to the questioning student, but addressing the entire class, I explained how for more than a decade my New Year’s resolution has been simply to learn more about trees, and that months earlier a New York Times profile of renowned medical biochemist and botanist Diana Beresford-Kroeger had been particularly instructive. Her endorsement of global forest restoration to mitigate the effects of climate change is clear, and some of her research has identified biochemical connections between forests and the sea.

Although I’m not certain my answer alleviated the student’s concerns, I’ll lead with trees if the question of hope comes up again. However, because of a subsequent encounter with another student’s direct question, my answer will also include a human element.

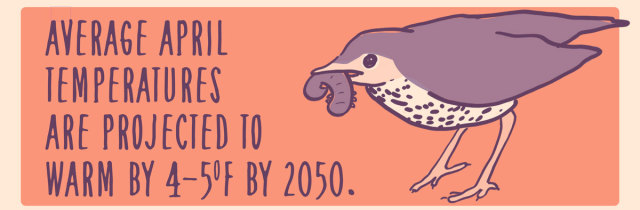

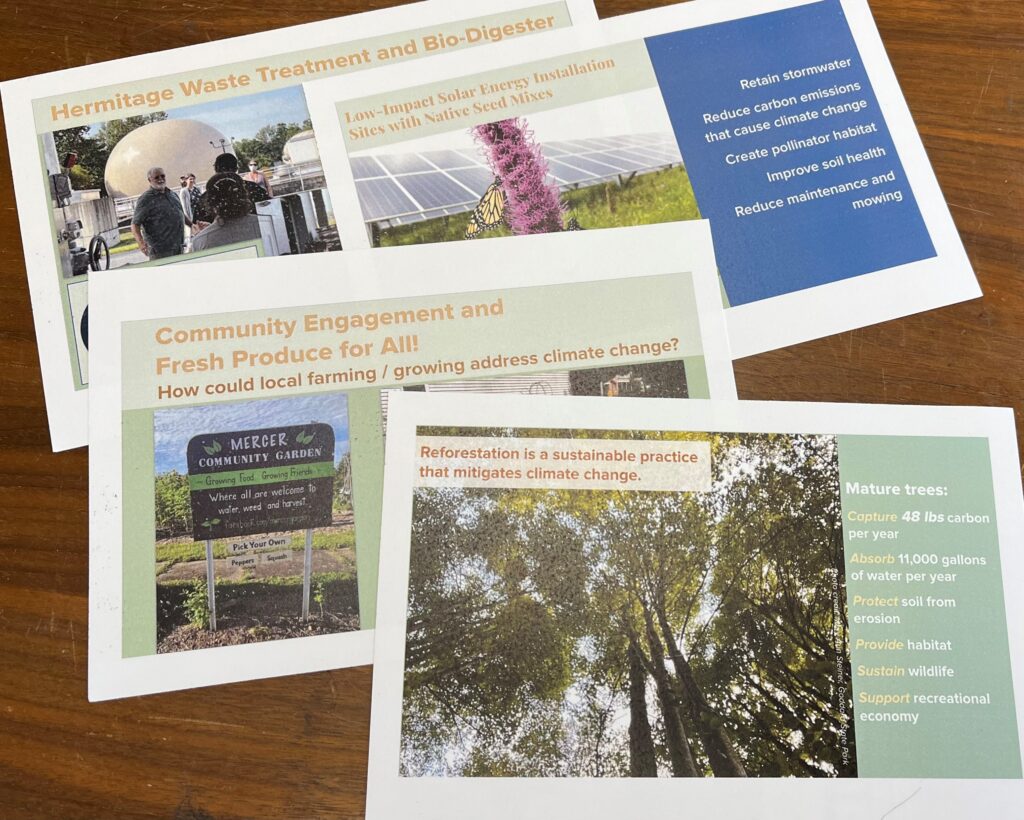

In early April, in collaboration with staff of the Mercer County Conservation District, I was one of two museum educators who spent a morning at that organization’s Munnell Run Farm headquarters assisting teams of local high school students in building climate change background knowledge as preparation for competition in the state-wide Envirothon. As encouragement for full participation in discussions, we relied upon colorful issues-focused information cards that were co-developed with partner organizations during the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership project. The climate cards were effective tools, but in one session a student with deep interest in climate change issues used a direct question to announce her enthusiasm for short cutting the process: “What should I do? I’m sold on all this, so tell me, as a high school student, right now, this month, this year, what should I be doing?”

I advised her to become as well informed as possible about climate change issues so she could better recognize solutions and mitigation efforts, and more effectively represent herself, her school, her family, and her community at relevant hearings or other public meetings. What I couldn’t articulate was that her engaged stance was something I could later point to as a sign of hope.

Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh offers free membership for teens. For additional information please visit the teen membership info page.

Patrick McShea is an educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Wolverine: Status Check for a Tournament Champion

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: September 7, 2023