In my very first “Introduction to Anthropology” class, the professor, a cultural anthropologist, tried to steer us away from archaeology by telling us it was a childish pursuit for those who liked to play in the mud and hunt for treasure. That sounded like it was right up my alley. I ended up spending my summers and an internship term working in Plymouth, Massachusetts, doing historical archaeology. In addition, I also spent a lot of time in the collections of the college anthropology museum, found that I especially loved working with textiles and basketry, and eventually learned to weave both.

Working in the eastern United States, it’s hard to find archaeological textiles; the very world is against it. Acid soils and a temperate climate create conditions where little organic material survives to be studied, except in the rare instances of charred material or pieces in contact with copper, or still rarer, textiles deposited in dry caves. Even then the evidence is usually fragile and fragmentary.

What eastern archaeologists find is a lot of pottery, and luckily for us, much of it has been impressed with cordage or fabric. As part of the pottery making process, clay coils were consolidated by being beaten with a wooden paddle, a tool frequently wrapped with cordage or fabric. This technique may have initially developed to create decoration, but the resulting roughened surface also made for a better grip, and the increased surface area caused pots to heat quicker in cooking.

Archaeologists study the long-vanished textiles by making durable impressions of pottery surfaces with modeling clay or dental impression material. The information revealed through the thorough study of such impressions is not limited to the determination of just what type of cord or textile was used in making the original object.

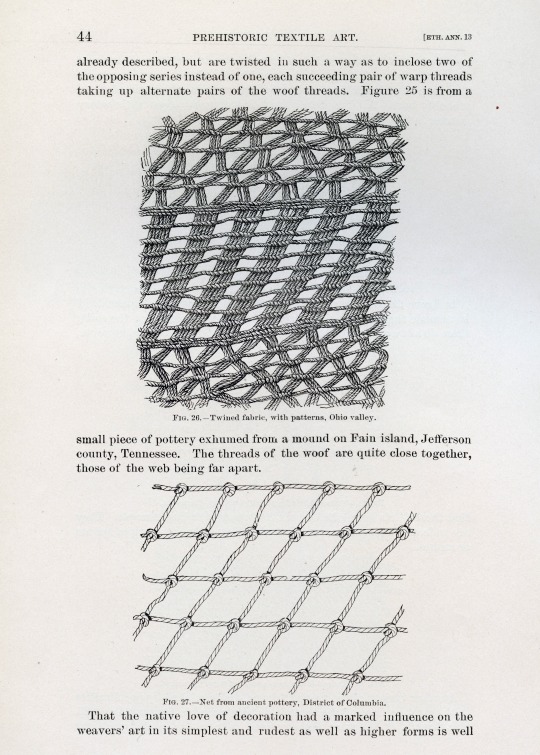

The making of pottery impressions to look at textiles was first published by the pioneering archaeologist, W.H. Holmes, in “Prehistoric Textile Art of the Eastern United States.” Holmes started his scientific career as an illustrator, and included schematic drawings of the textile structures in his article.

When I worked at what is now the Florida Museum of Natural History, I got interested in the earliest pottery found in Florida, from what is known as the Orange culture. Dating from about 1500 BCE, these distinctive pieces were thick and very simply decorated. Their most interesting feature, at least to me, was that the clay pot bottoms had been pounded flat on matting, and the applied force made deep impressions. At least three different techniques were used, with variations and patterns within each, including several different matting materials.

In one instance, a thick pot sherd had a smooth top surface, but a deep dent in the bottom; evidence the potter hadn’t removed a small pebble that was under the mat before the pot making.

Many studies have been done since W.H. Holmes, looking at such things as direction of the twist in cordage—a majority of right-handed or left-handed twist could indicate a culture-wide preference. Similar twist types in neighboring geographic areas might indicate related cultural or kin groups, while different twist types could indicate a cultural boundary. The type of material used [soft fiber, hard rods, flat cane-like splints] may indicate cultural preference, or perhaps the materials available in the immediate environment.

One study by Dr. Penelope Drooker, Mississippian Village Textiles at Wickliffe, introduced me both to some incredible textile impressions in pottery and the information that can be gleaned from them. Drooker’s work also analyzed and illustrated some textiles preserved in dry caves of eastern Tennessee, part of the Cherokee people’s ancestral lands. Among the materials she studied were skirts and bags from the Cliffty Creek Cave, artifacts now housed at the Smithsonian Institution. Working with the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, NC, I was able to re-introduce members of the tribe to one of the oldest weaving techniques of their ancestors. A few tribal members have visited the Smithsonian to photograph Cliffty Creek Cave pieces [as have I], and are now making skirts for use in festivals and pageants. Several are making decorated bags for their own use, and for sale.

One of the great things about textiles or pottery is that you could spend your entire life studying them, and still not learn all that these materials embody–techniques, cultural traditions, and art, all rolled into one. My grandfather, who kept his faculties up to his death in his mid-90s, said, “The day you stop learning is the day you start to die.” I try to live by that.

Deborah Harding is the Collection Manager of the Section of Anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References and further reading:

Drooker, Penelope Ballard 1992 Mississippian village textiles at Wickliffe, University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa and London

Holmes, W. H. 1896 “Prehistoric Textile Art of the Eastern United States” Thirteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1891–1892, Government Printing Office Washington, pages 3–46.

Milanich, Jerald T. and Charles H. Fairbanks 1980 Florida Archaeology Academic Press: New York

Petersen, James B [editor] 1996 A most indispensable art: native fiber industries from Eastern North America, University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville

Related Content

The Unseen Museum: Ka’apor Necklace