Although much of the Western world recognizes January 1 as the first day of the new year, many other cultures around the globe celebrate Lunar New Year, an alternate calendar system based on the cycles of the moon. Lunar New Year began on February 12 this year, ushering in, according to repeating cycles of the traditional Chinese zodiac, the Year of the Ox. While bovines hadn’t evolved by the Mesozoic Era, there were plenty of dinosaurs that could be compared to an ox. So, in honor of Lunar New Year, this month’s Mesozoic Monthly features Nasutoceratops titusi, a ceratopsian with a rounded nose and curving, bull-like horns!

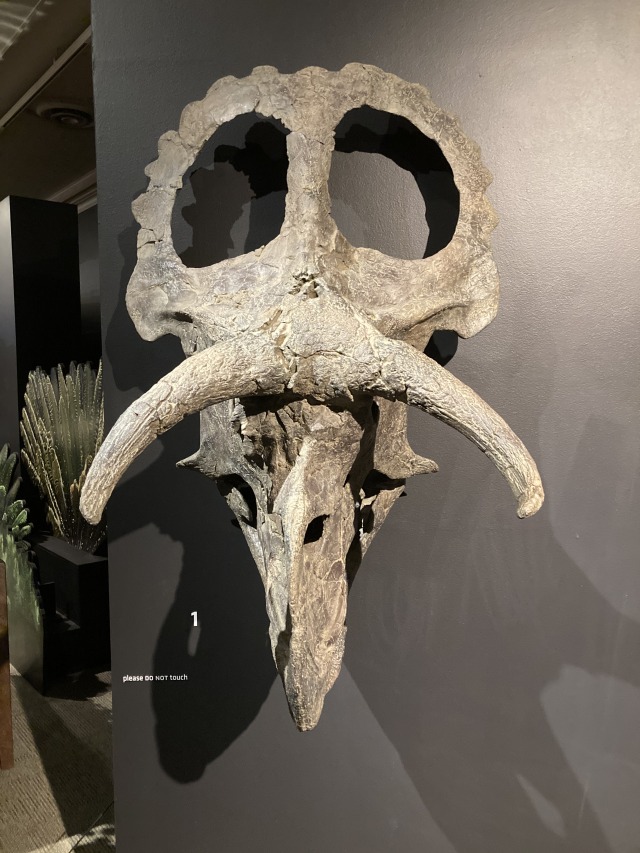

Ceratopsian dinosaurs are famous for their huge, elaborate skulls adorned with ornate frills and large horns. Several different bones make up these unique structures. If you haven’t taken an anatomy class, you may not have realized that your skull is made up of several bones that fuse together as you age (fun fact: baby humans have more bones than adults, and this is why!). The horns above a ceratopsian’s eye arise from the postorbitals, bones that sit right behind the eye hole in the skull. The frill is made of two types of bones: the parietals, which make up the central part of the frill, and the squamosals, which act as the corners. Humans actually have both of these bones: the parietal is the large bone at the crown of your head, and the squamosal is fused into the temporal bones above your ears. The bones that form the nose horn of a ceratopsian are aptly named nasals, and we have them too, supporting the cartilage structure of our noses. Of course, our bones are shaped markedly different from those of Nasutoceratops, but the fact that we (and all other vertebrates, aka animals with backbones) have similar skeletal compositions is a feature we inherited from our most recent common ancestor.

The skulls of ceratopsians are huge: they grow as long as one third of their body length! The skull of Nasutoceratops was almost five feet (1.5 meters) long, and although we don’t have many bones from the rest of its body, paleontologists estimate that the animal was almost 15 feet (4.5 meters) long. But Nasutoceratops wasn’t even the largest ceratopsian! The most famous ceratopsian, Triceratops, has a skull that can reach a whopping 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) long, but even that isn’t the largest. The largest skull of all dinosaurs belongs to Pentaceratops (sometimes called Titanoceratops), a ceratopsian with an absolutely massive 8.7 foot (2.7 meter) skull!

Nasutoceratops shared its environment with several other species of ceratopsian, including Kosmoceratops richardsoni and Utahceratops gettyi. Each of these had very different-looking headgear. Nasutoceratops, as previously mentioned, had bull-like horns and a big round nose. Kosmoceratops, in contrast, had weird horns at the top of its frill that curled forward and down, almost like it had bangs, and Utahceratops had short postorbital and nasal horns but a large frill surrounded by spikes. Since all these ceratopsian species lived together, it’s likely that the unique skull ornamentation of different species helped with intra-species recognition (in addition to other functions such as sexual signaling or defense from predators). This meant that each animal could regard shared cranial features as a way to tell who was part of their species. These visual cues might have been especially important for ceratopsians born during the Year of the Ox – according to the Chinese zodiac, “oxen” have poor communication skills, so clear and direct signaling is crucial!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What kind of dinosaur is a megaraptorid?