by Andrea Kautz

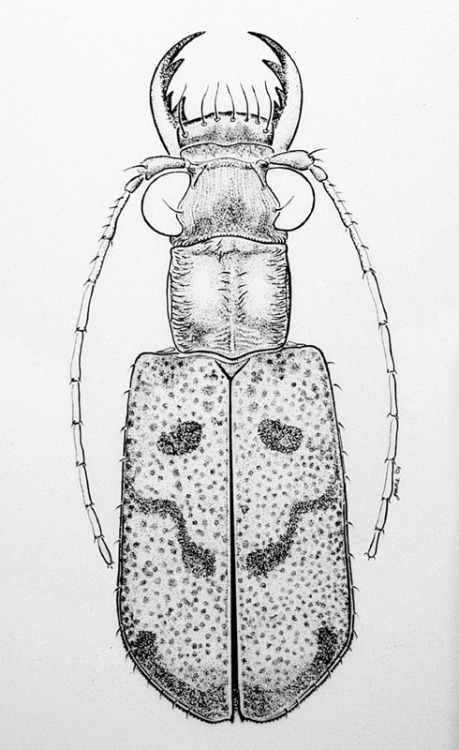

From the name of them, you may guess “blister beetles” are insects you might not want to handle. However, they sure are beautiful to look at! We’ve been noticing blister beetles out and about at Powdermill over the last week or so. Some fly around clumsily, while other flightless species scurry among the leaf litter. Beetles in this family (Meloidae) secrete a defensive substance called cantharidin, a skin irritant that can cause blistering. They are also very toxic when consumed, and can be fatal for livestock if present in the hay supply.

Blister beetles are parasites, mostly in the nests of ground-nesting bees and wasps. Watch this short video clip to learn more about their life cycle. Spoiler alert: In this species, the newly hatched beetle larvae clump together and attract a male bee using a fragrance, and then transfer to the female he mates with, ultimately gaining access to her nest, where they feed on both the pollen provisions and the bee larvae themselves!

Whether larvae or adults, these striking beetles certainly have a fascinating dark side. There is always more than meets the eye when it comes to entomology!

Andrea Kautz is a Research Entomologist at Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Oh Deer, That’s a Lot of Parasites!

Fourth of July and the Firefly

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Kautz, AndreaPublication date: May 26, 2021