In the northeastern United States, we often think of spring as a time for wildflowers. But the fall is, too.

It is easy to be distracted by the beautiful fall foliage, when our landscape turns brilliant shades of red, orange, and yellow. But when many plants are shutting down for the winter, others are just kicking into gear.

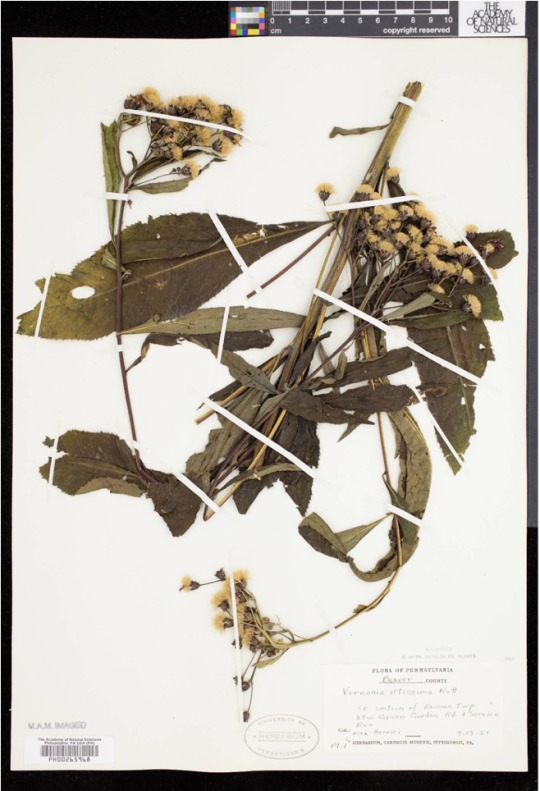

Many wildflower species bloom well into fall, both in open areas and in the forest understory. One group of plants are the fall blooming “asters.” In same plant family as sunflowers and dandelions (Asteraceae), Aster was once a very large plant genus in our native North American flora (somewhere along the lines of >175 species!), but as we learned more about the evolutionary relationships of these plants, they have since been split into multiple genera (plural of genus). In fact, there is only one “true” Aster in Pennsylvania, Tatarian aster (Aster tataricus), which is actually not even native to Pennsylvania! Regardless of the scientific name, these plants are commonly referred to as asters. And they put on quite an autumn show in Pennsylvania.

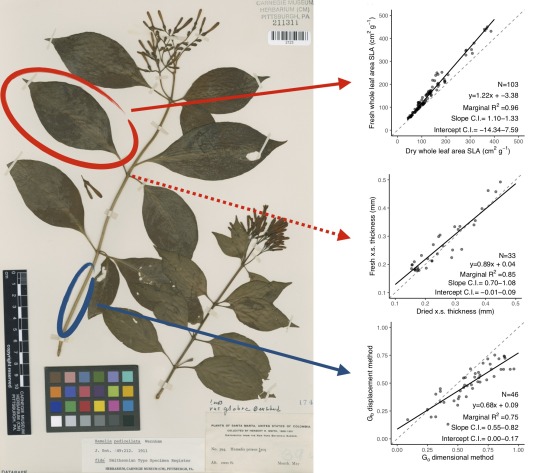

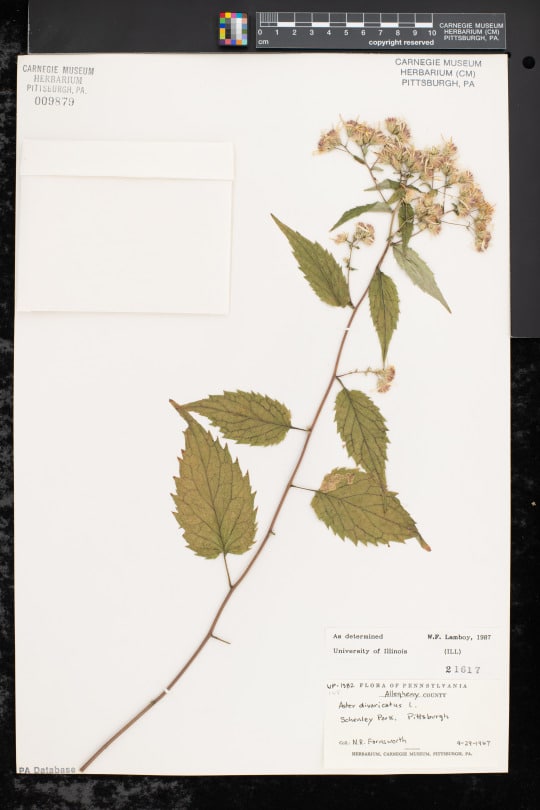

Perhaps one of the most common woodland asters in Pennsylvania is white wood aster (Eurybia divaricata, formerly known as Aster divaricatus). This specimen was collected September 29, 1967 by N.R. Farnsworth in Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park. This species can still be found in Schenley Park, and many parks, woodlands, and wooded roadsides across Eastern North America.

Fall foliage is beautiful in Pennsylvania. But don’t forget to look down at the flowers, too!

Find this white wood aster specimen here: https://midatlanticherbaria.org/portal/collections/individual/index.php?occid=11826562

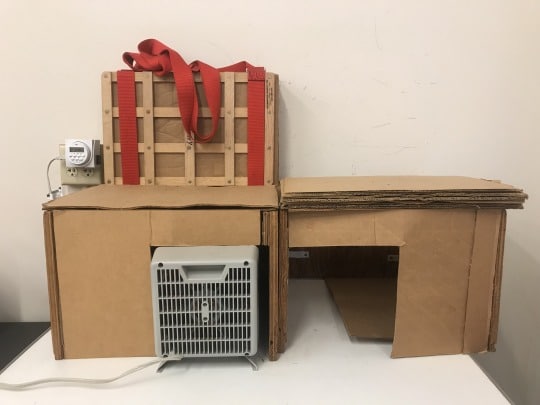

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Collected on This Day in 1944: Squarrose Goldenrod