Chestnuts (used to be) on Chestnut Ridge

And across the entire state of Pennsylvania.

American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was once a very common tree, native from Maine to Mississippi. In the heart of the Appalachians, the historical range covered the entire state of Pennsylvania. I say “historical” and “once a very common tree” because it is no longer. You may occasionally stumble upon an American chestnut tree, especially small trees and saplings persisting as sprouts from the large trees that graced our landscape a century ago. Older trees, with mature fruits, are quite rare.

In fact, some estimates suggest American chestnut accounted for one in four trees in some forests! So, what happened? In the early 1900s, a disease caused by a pathogenic fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) was accidentally introduced with imported Asian trees. It was first recorded in New York City in 1904. In a matter of decades, American chestnut was nearly decimated by this disease known as Chestnut blight.

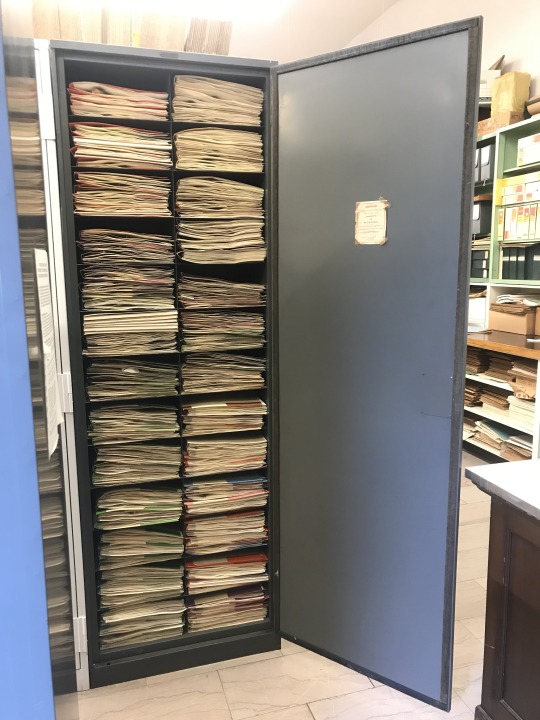

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History herbarium captures this change in our forests.

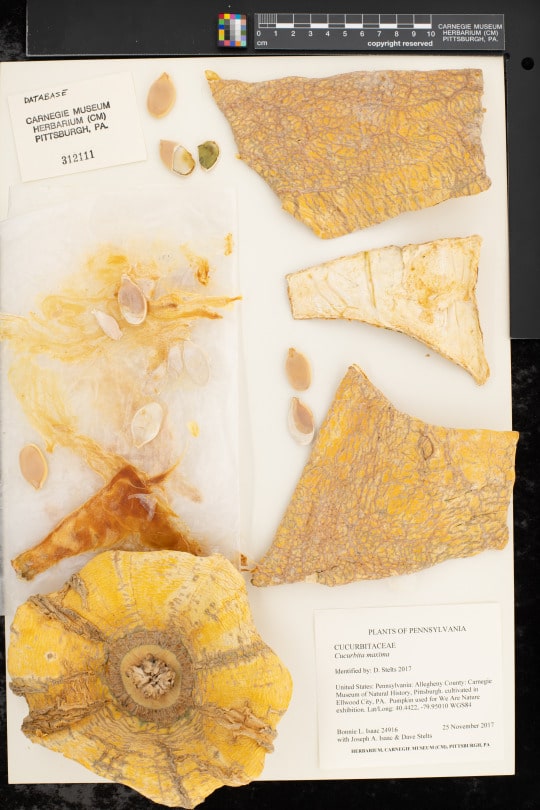

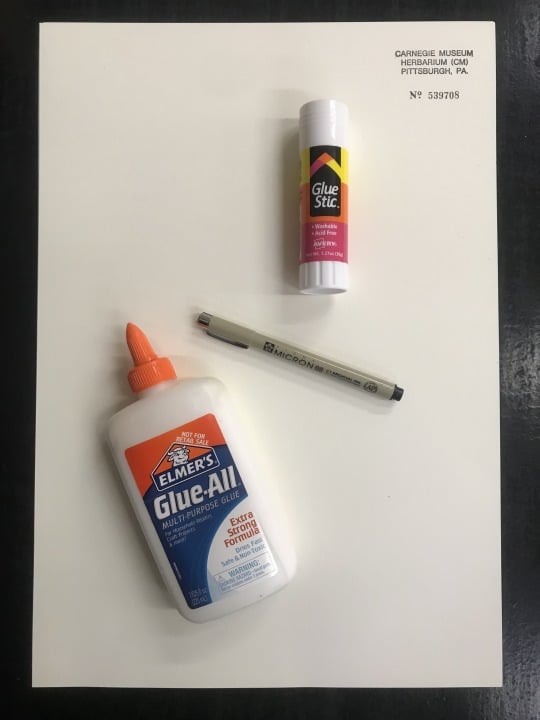

This specimen of American chestnut was collected by influential Carnegie Museum curator Otto Jennings on October 21, 1922 on a field trip of the Botanical Society of Western Pennsylvania to Chestnut Ridge, near Derry Township, Pennsylvania. Chestnut Ridge is a ridge of the Allegheny Mountains, presumably named for its (once) many American chestnuts.

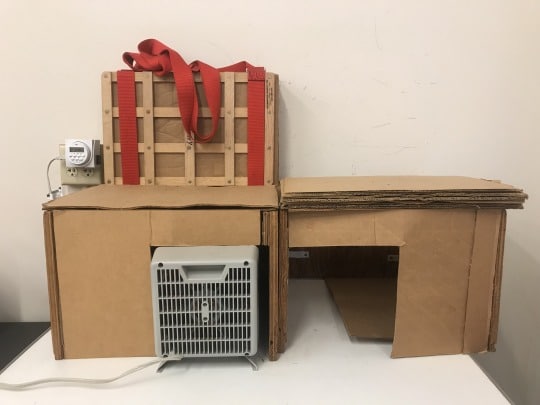

This specimen is from the fruit collection of the herbarium. These specimens are different than the “standard” pressed flat specimens on paper. Instead, they are stored to maintain their three-dimensional structure.

Note the note made by Jennings on the label on this specimen: “Trees from ¼ to all killed by blight.”

The case of the American chestnut is an interesting one. It served important cultural and ecological roles; some even calling it a “keystone” species. There is no doubt that the functional extinction of American chestnut ricocheted through the ecosystem, causing long-term biological changes. Many of these changes we may not know. Yet, at the same time, despite the species importance, our forests continue. Presumably other species have filled the functional and physical space of American chestnut.

Disease and pest outbreaks in Pennsylvania’s forests continue. Many of our critical tree species are likely to decline in coming years and decades. Some iconic species have already declined or are at risk. These include our ash species (mortality caused by introduced Emerald Ash Borer), American beech (Beech leaf disease, Beech bark disease caused by an introduced scale insect), and eastern hemlock (mortality caused by introduced sap sucking bug, the hemlock woolly adelgid)…to name only a few threats.

What will Penn’s woods look like in another 100 years?

Our collections document the past and present to inform our decisions for the future.

Find this American chestnut specimen here (along with 268 others!): https://midatlanticherbaria.org/portal/collections/list.php?db=328&includecult=1&taxa=Castanea+dentata&usethes=1&taxontype=2

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.