Sensory Friendly Trick or Treat

Put on your favorite costume and head to Carnegie Museum of Natural History for a sensory-supportive Halloween Trick or Treat! Museum galleries will have reduced audio and visual elements and calm spaces with support materials. Pick a seat around our story time faux campfire, meet a scaley live animal ambassador, and trick-or-treat your way through the museum at this all-ages and all-abilities event!

-

· Trick or Treat through the museum galleries

· Gift shop will be open

· Seasonal story time around our faux campfire

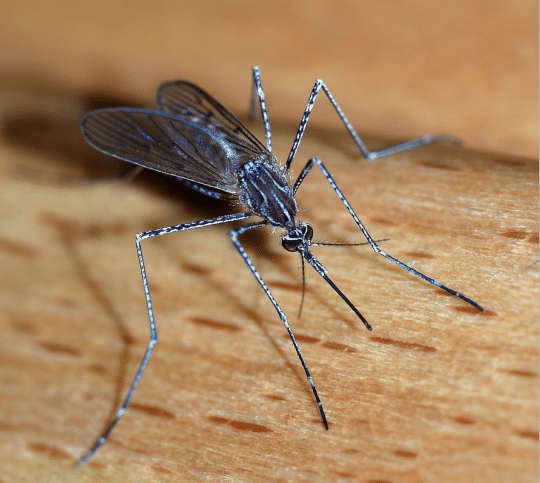

· Sensory Friendly Live Animal Meet and Greets

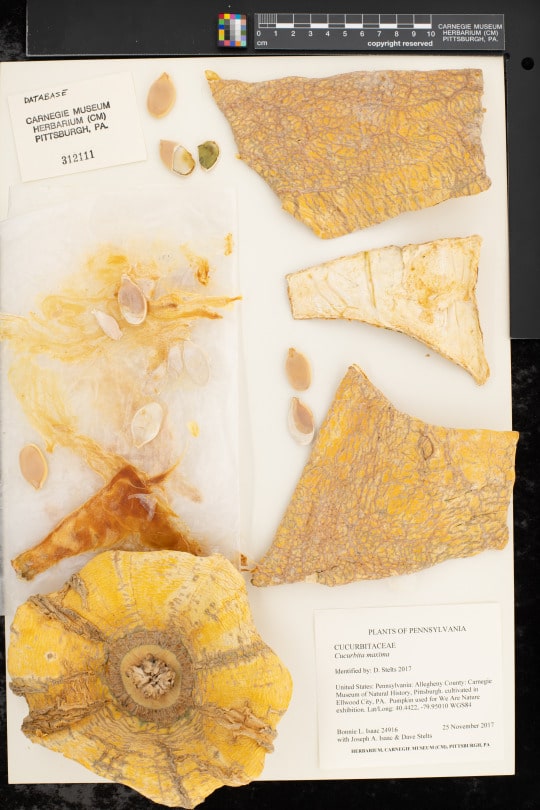

· Jumping spider specimens from behind the scenes of the insect collection

· Friendly staff who are ready to chat for as little (or as long) as you’d like about dinosaurs, rocks, gems and more!

Costumes cannot include masks that cover the entire face, weapons, or weapon-like objects. Safety face masks are permitted, but not required.

Sensory Friendly Trick or Treat

Friday, October 27, 6 p.m. to 9 p.m.