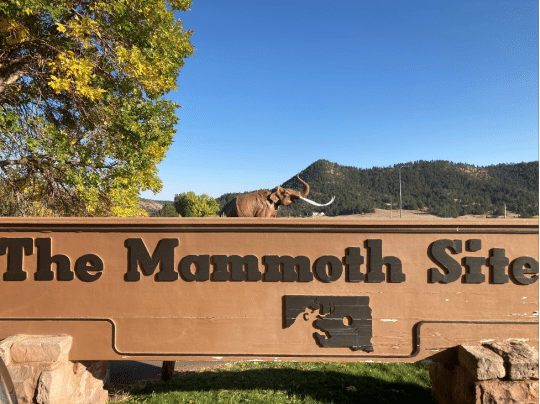

Did you know that not all museums display their fossil specimens mounted in life-like poses? At The Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, South Dakota, visitors view fossils “in situ,” or as they were discovered, and because excavation continues year-round, this unique museum is also an active dig site.

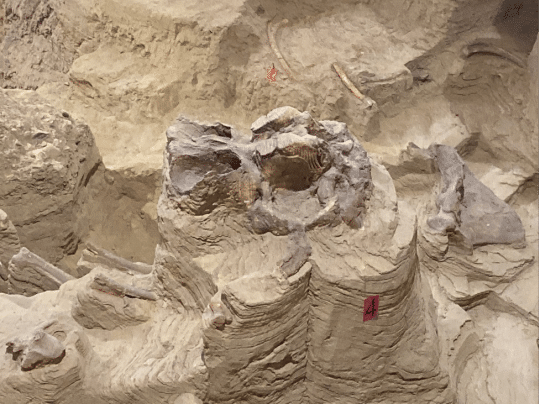

Instead of being held in place by the fabricated support structures that are so crucial to traditional fossil displays, bones at The Mammoth Site rest on sediment and appear in the same orientations in which they were found. The remains of more than 60 Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) have been documented here to date, comprising the world’s most extensive collection of skeletons of these Ice Age elephant relatives.

The Mammoth Site was discovered in 1974 when the landowner decided to build a housing development on the 14-acre plot. While the heavy machine operator was bulldozing a small hilltop, he found tusks and bone. Construction stopped and officials at four colleges were contacted, but none expressed interest in the find. Fortunately, the son of the heavy machine operator, who had taken geology and archaeology courses in college, was able to gain interest from one of his former professors, who was then conducting fieldwork in Arizona. When the professor arrived at the site a few days later he recognized the exposed bones of four to six individual mammoths and the potential for more nearby. He arranged for a field crew to salvage and stabilize the visible bones, teeth, and tusks, and returned the next summer with a group of students to do more excavating. A complete skull with tusks attached was the prize find of these more organized recovery efforts, and by the end of the summer the landowner had decided the tract’s highest value was as a place for scientific study.

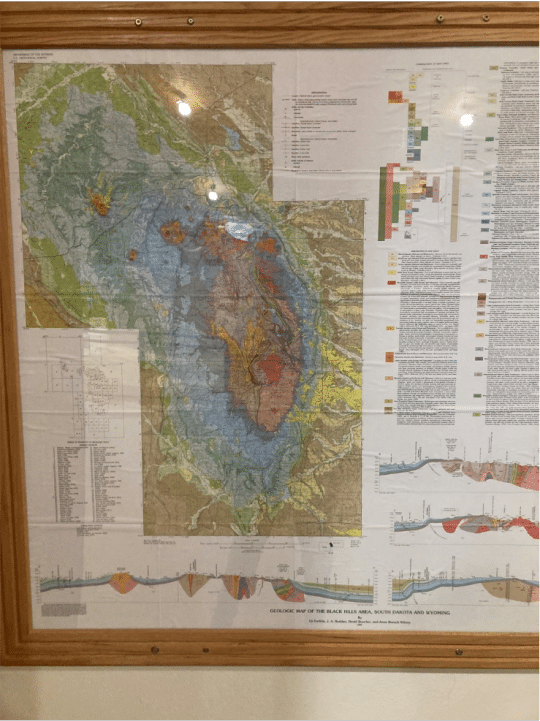

I recently had the opportunity to visit The Mammoth Site, which is located in the Black Hills, a scenic region of green pine trees and deep red earth. Once you purchase your admission, you are directed to a theater where a looped video introduces the relevant geologic history. The site is the result of a sinkhole that developed when groundwater dissolved the limestone layers through which it flowed. Subterranean water-filled caverns were an early product of this process, but as the water table lowered the caverns weakened and collapsed, resulting in a deep sinkhole with a chimney-like shaft, through which a warm artesian spring percolated to the surface. In three phases over a period of 750 years, the sinkhole refilled with sediment and the remains of mammoths and other creatures before it was eventually reduced to a mud wallow.

After the theater, the bonebed is the next stop. The museum has a special app that can be listened to with headphones for a tour of the bonebed. The bonebed room is very large and naturally lit and has a high beam ceiling with windows at the top of one wall. There is a crane attached to the rafters that is used to move any specimens that need to be permanently removed from the ground. Because a large tusk can weigh over 100 pounds, and skulls far more than this, this overhead crane is an essential tool.

How, you ask, do researchers know there are over 60 individuals in the sinkhole? For every mammoth or person or other critter with a skeleton, there are a certain number of each bone in the body. Because mammoths have two tusks it is possible to count the number of tusks in the bonebed, 123, and divide by two to calculate the presence of at least 62 individuals.

Determining the sex of a mammoth is possible when its pelvis is well-preserved with minimal crushing or distortion. By measuring a specific spot on the pelvis and the width of the pelvic canal at a certain area, and comparing these two measurements, it can be determined whether the pelvis belonged to a male or female mammoth. This calculation is possible because males are generally larger than females, and also because females had a proportionally larger pelvic canal to aid in giving birth. Mammoth remains recovered at The Mammoth Site have all been male. Although the presence of more than 60 males but no females at the site may seem surprising, studies have shown that “natural death traps” such as The Mammoth Site captured many more males than females. This may be because, rather than living in herds led by a knowledgeable matriarch, relatively inexperienced male mammoths typically traveled alone, making them more likely to get stuck in these kinds of traps.

It is also possible to age a mammoth using growth rates of bones and the state of fusion of the epiphyses (the ends of the limb bones); however, it is most accurate to age these animals by measuring their teeth. The length and width of the occlusal (= chewing) surface is then used to verify which of their six sets of teeth they were using at the time of death. Generally, a mammoth’s life span could be as long as 60 to 80 years, an age when the animal would be relying upon its sixth set of teeth. When these teeth wore down, starvation would follow. Dental comparisons at The Mammoth Site indicate that most of the remains represent mammoths that were between 15 and 29 years old when they died, with a few in their late forties or early fifties.

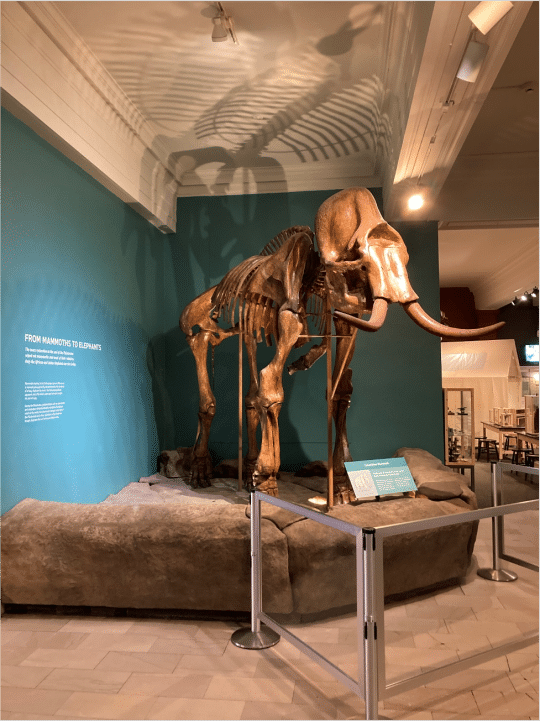

When you next visit Carnegie Museum of Natural History, be sure to head to Pleistocene Hall, where we have our very own mounted Columbian mammoth skeleton on display!

Linsly Church is a Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What kind of dinosaur is a megaraptorid?