by Hannah Smith

I am a fries-on-salad, haluski dinner, dairy farm heritage kind of Western Pennsylvanian. I grew up near Venango and Crawford County and had a rural childhood. I went to a small school with about 300 kids in K-6th grade. Around 4th grade, I remember taking a field trip to Titusville, Pennsylvania. I remember seeing the familiar road signs and buildings as our bus gassed along the back roads. I had family in the Titusville and Oil City area, so it was a familiar route to take with my parents. I remember thinking, even at that young age, that the area looked worn and just, well, tired. But I was too young to grasp how this tired little town’s geology had changed the global economy and course of human history. When I was older, I pursued a degree in geology and began to understand more about my local community.

Our field trip took us to Titusville, Pennsylvania to visit Drake’s Well, the first commercial oil well in the United States. The site is named after the well’s driller, Edwin L. Drake who in 1859 struck oil outside of Titusville for the Seneca Oil Company. The company took the name from the Seneca Nation, one of the original Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy, who had long made use of the resource Drake sought by skimming naturally-occurring slicks of petroleum, or unrefined oil, from the surface of local waters. These Indigenous people, who were removed from their native lands in the 1700s, 1800s, and 1900s, did not benefit from the Seneca Oil Company.

In the early 1800s oil was an unwanted by-product from salt wells (wells used to mine salt), and before that, a traditional medicine. In small doses, oil was used to treat respiratory diseases, epilepsy, scabies, and other ailments¹. Even today, chemicals made from the refining of petroleum are responsible for many of our modern medicines. Ointments, antihistamines, antibacterials, cough syrups, and even aspirin are created from chemical reactions created from petrochemicals².

However, the purpose of Drake’s Well was to produce oil for refining into kerosene for lamps, and thereby provide an alternative to the whale oil then used to illuminate homes and workplaces. Salt wells used water to dissolve salt source rock, and then carry the resulting brine through piping to the surface where it would be evaporated to leave salt as a solid residue. Although this method works for producing salt, it was far less efficient for producing oil. Productive oil drilling required new techniques, and one of Drake’s most important innovations was the “drive pipe,” sections of cast iron pipe driven into the shaft to protect the drill bit from water and cave-ins. Through experimentation and innovation, on August 27, 1859, Drake struck oil when his drill reached a depth of 69.5 feet.

While Drake’s Well was not the most productive, or largest oil well, the Titusville site is globally significant because it kick-started the petroleum drilling revolution that eventually changed global economies and environments. While Edwin Drake lived a hard life even after his discovery, he is still considered the father of the modern petroleum practices and industry³.

When my field trip class arrived at the Drake’s Well Museum I remember seeing an odd looking wooden building with an awkward chimney-like structure on one side. We were led through single-file so everyone could get a look at the steel machinery used in the drill, and the pipes that dispersed oil into wooden barrels clustered in the building. In my 10-year-old brain there is no way I could properly fathom that this discovery was related to many of the comforts and conveniences I took for granted in my life, such as cars, heating, electricity, plastics, medicines, and even the asphalt roads that we drove on. Why was Titusville special? More specifically, why did western Pennsylvania have oil in the ground?

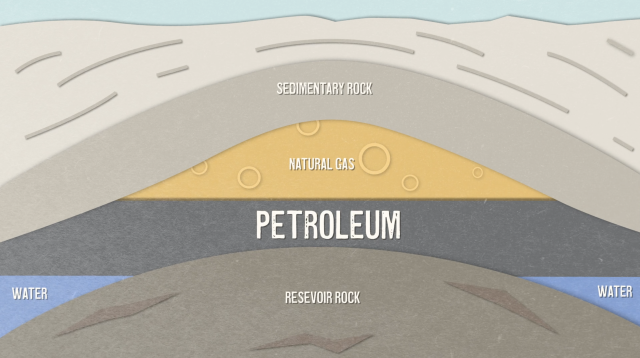

From about 490 to 360 million years ago, during the span of geological time known as the Ordovician Period and Devonian Period, most of what is now Pennsylvania was an ocean basin teeming with life. Pre-Appalachian Mountains systems eroded over time and deposited sediment of sand, silt, and mud that mixed on the seafloor with the dead plant material. Currents at the ocean bottom were minimal, leaving the accumulating sediments and organic material relatively undisturbed and oxygen-free. Without oxygen, bacteria that normally break down organic material could not act. A thick, black, anoxic ooze formed, preserving the organic material. Over millions of years, forces caused by plate tectonics generated enough heat and pressure to compact the sediments into rock and “cook” the organic material into petroleum.

If you’re from western Pennsylvania, you’ve probably heard of the Marcellus and Utica shales. The natural gas extracted from these rock units formed in a similar way to petroleum but was subjected to a much longer period of heat and pressure.

With Edwin Drake’s success, and layers of oil-bearing rock relatively close to the surface, Titusville boomed. The year Drake drilled his first oil well, Titusville only had 250 residents. However, by 1865 the population increased to 10,000. Nearby Pithole City, now a ghost town, had 50 hotels during the oil peak of the area around 1866. This boom was short lived as other drilling companies began operations in the area and excess production lowered oil prices. Companies picked up to look elsewhere almost as quickly as they appeared⁵. While Titusville boomed and busted, the oil industry itself was growing. Drake drilled for a product to compete with whale oil, but the oil industry underwent phenomenal growth because the demand for its product grew as a lubricant for engines and many other types of machines, a resource for heating on a distributed scale, and as a refined fuel for developing motorized vehicles. Two World Wars during the first half of the 20th Century and the population explosion of the 1950s further increased demand for petroleum. During the Century’s latter half advancements in oil drilling technology made ocean drilling platforms a reality, and with them an increase in oil production as well as an increase in negative impacts due to devastating oil spills.

As of 2016, the world consumed over 97 million barrels daily⁶. So what does combusting 97 million barrels of oil a day, a resource from below the surface, mean for the Earth’s atmosphere? The burning of fossil fuels produces greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. Greenhouse gases absorb heat from the sun that the earth’s surface reflects back out into the atmosphere, similar to how a blanket traps in body heat. Burning fossil fuels causes climate change by increasing the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, thickening the “blanket” around the earth, and increasing the global average temperature. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in 2019 greenhouse gas CO₂ emissions totaled 33 gigatons, or 1 billion metric tons, or about the weight of 1.5 billion school buses⁸. Climate change is responsible for increased frequency and severity of weather disasters, wildfires, and flooding, to name a few negative impacts. The abundant CO₂ in our atmosphere equilibrates with and diffuses into our oceans, causing the water to become more acidic and eroding the calcium carbonate structures of coral and other marine organisms. Climate change does not just affect wildlife, it also affects the lives of Pennsylvanians. In Pennsylvania climate change is likely to lead to increasing home insurance rates, higher taxes to replace infrastructure, longer allergy seasons, increasing heat stroke rates in citizens, rising food costs due to crops damaged by erratic weather and higher temperatures, and decreasing water quality and availability due to large storms causing water contamination⁷.

Early organisms were buried by sediment 488 to 360 million years ago and altered into petroleum by heat and pressure. For thousands of years, Earth’s petroleum reserves were largely untouched. Innovator Edwin Drake changed petroleum’s role by successfully drilling the first commercial oil well in North America that August day in 1859. Petroleum became a global commodity, eventually fueling a fast paced modern life. Now in the 21st century, the burning of fossil fuels, such as petroleum, is causing worldwide rapid climate change.

When I was on that field trip to Drake’s Well in 4th grade, we did not discuss the global or local implications of petroleum. This resource is responsible for many of the day to day conveniences that have come to define contemporary life, but it also feeds environmental change that is forcing a “new normal,” and will cause an existential threat to humanity. I could not have fathomed that this global resource had its start in my own family’s backyard. I think that Drake’s Well is a good reminder that Earth-changing innovations can happen anywhere. I don’t think Drake could have predicted the scale to which his discovery would change society and the environment over the next 160 years, in the same way that most people do not realize how their small individual actions are affecting the larger social-ecological systems, and sustainability of all life on Earth. Although individual actions can negatively affect Earth, they can also be positive. Who knows, the next innovation to combat anthropogenic climate change may be happening in your backyard. Wind and solar farms have been developing and growing throughout Pennsylvania since 2007, providing an alternative option for electric energy use.

I started having more appreciation for the Earth Sciences as I got older. This eventually led me to obtaining a bachelor’s degree in geology, interning with the National Park Service at the Hagerman Fossil Beds in Idaho, and working in mapping for a few years before returning to school for illustration and design in hopes to marry the sciences and arts together. While obtaining my geology degree I met my now husband who has a Master’s in Structural Geology, and worked in the natural gas field for five years before making the switch to environmental geology. Our family’s income was supported by the fossil fuels industry for a time, and therefore we understand a decent amount of the ethics and controversy that is in the industry. However we are both very invested in the earth sciences and look forward to more sustainable tech preserving a better environment for the future.

Hannah Smith is an intern in the Section of Anthropocene Studies. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References:

1 Early Medicinal Uses of Petroleum 2015 https://daily.jstor.org/petroleum-used-medicine/

2 Modern Uses for Petroleum in Medicine 2019 https://context.capp.ca/articles/2019/feature_petroleum-in-real-life_pills

3 Drake’s Well History of Petroleum 2016 https://www.aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/american-oil-history/

4 Description of petroleum formation 2014 http://elibrary.dcnr.pa.gov/GetDocument?docId=1752503&DocName=ES8_Oil-Gas_Pa.pdf

5 The boom and bust cycle of the oil industry 2015 https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/23/business/energy-environment/oil-makes-a-comeback-in-pennsylvania.html

6 World Oil Statistics 2016-Current https://www.worldometers.info/oil/

7 List of the Effects of Climate Change on People and how to protect yourself 2019 https://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2019/12/27/climate-change-impacts-everyone/

8 International Energy Agency 2019 https://www.iea.org/articles/global-co2-emissions-in-2019

9 Drake’s Well Museum https://www.drakewell.org/

10 Seneca-Iroquois National Museum https://www.senecamuseum.org/

11 Seneca Nation Oil Process in New York State https://nyhistoric.com/2013/10/seneca-oil-spring/

Related Content

Understanding Fossil Fuels through Carnegie Museums’ Exhibits

What Does Climate Change Mean for Western PA Farmers?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Smith, HannahPublication date: May 17, 2021