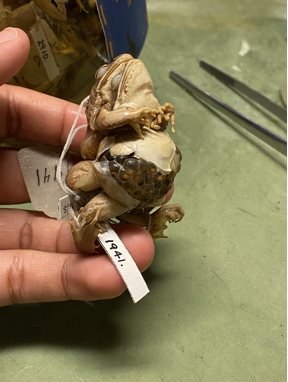

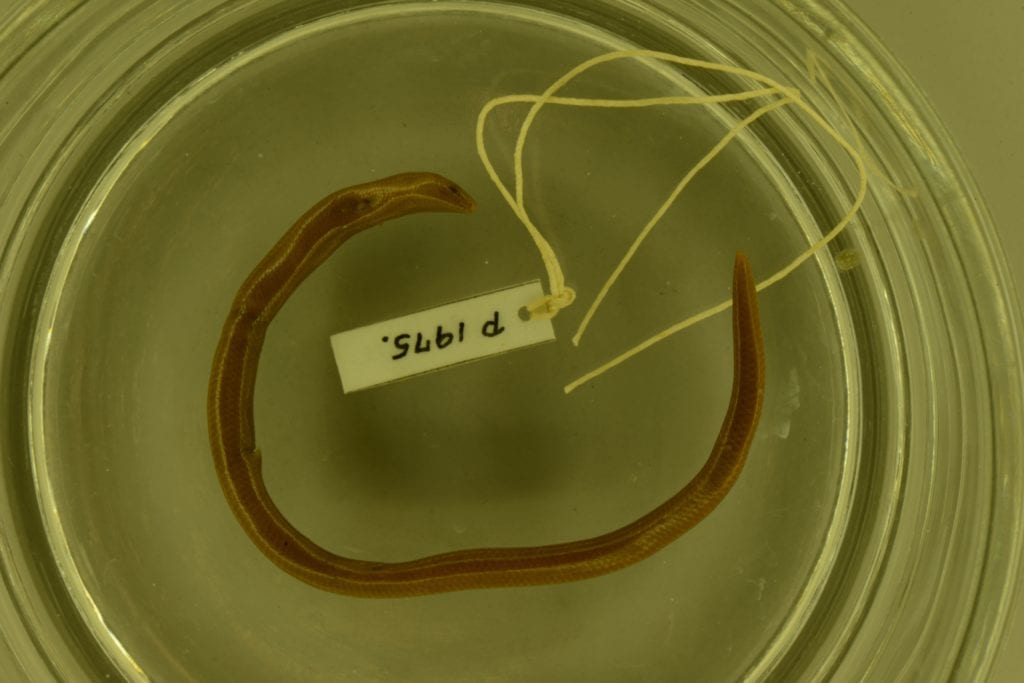

Researchers from Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) and international colleagues describe seven species of skinks from the African nation of Angola that are new to science. In a study recently published in Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, the research team review all the occurring species of the genus Trachylepis in Angola and conclude there are seven new species.

Two of the new species names, Trachylepis attenboroughi (“Attenborough’s Skink”) and Trachylepis wilsoni (“Wilson’s Wedge-snouted Skink”) honor iconic naturalists David Attenborough and Edward O. Wilson, respectively. The other names honor the late French herpetologist Roger Henri Bour, Angolan herpetologists Suzana A. Bandeira and Hilária Valério, the Angolan chieftain Mwene Vunongue (1800–1886), and the Ovahelelo ethnolinguistic group in gratitude for supporting and welcoming the research team and permitting them to study fauna of their lands.

“It is an honor to name two new species after Sir Attenborough and E.O. Wilson,” said Mariana Marques, CMNH Collection Manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. “Both naturalists played a crucial role in my academic and professional paths, and their legacy definitely sparked my passion for African wildlife. We hope that naming two species in recognition of such inspirational naturalists can raise awareness worldwide that there are still new species to be discovered and described while many others are becoming extinct before they are even discovered. We are in a race against time to save our biodiversity, we cannot preserve what we do not know.”

“It’s equally important to acknowledge the people of Angola,” said CMNH Research Associate and CIBIO/BIOPOLIS Researcher Luis Ceríaco. “We owe so much to them, including scientists who have contributed vital knowledge of the country’s beautiful biodiversity and the people who live on this land and who welcomed us and supported these endeavors. Both Suzana and Hilária started participating in this project as students, and now they are both leaders in their respective fields in Angola. They are training a new generation of Angolan biologists and conservationists. Honoring them with these two new species is a way to celebrate the new generation of African naturalists!”

The description and naming of new species provides critical insights for biologists, contributes to our understanding of the evolutionary processes that shaped today’s biodiversity, and updates the catalogue of life on Earth. As biodiversity grows ever more vulnerable on a worldwide scale, a clear understanding of the real number of species and their distribution is fundamental to developing effective conservation plans.

Angola, a country in southwestern Africa, is one of the most biodiverse countries on the continent, with high levels of endemism, or species that occur nowhere else in the world. This diversity is due to the county’s geographic position and wide diversity of biomes—including tropical rainforests, savannahs, and deserts, providing the specific habitats for species to adapt and speciate. Angolan biodiversity serves as a trove of new scientific knowledge, due in part to the armed conflicts that have engulfed the country for more than four decades, impeding research.

In addition to Marques and Ceríaco, the research team includes Diogo Parrinha, CIBIO/BIOPOLIS PhD Candidate; Arthur Tiutenko, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen/Nuremberg Assistant Professor; Jeffrey Weinel, American Museum of Natural History Postdoctoral Fellow; Brett Butler, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico PhD Candidate; and Aaron Bauer, Villanova University, Professor.