Every herpetologist has an origin story – a time in their life when they realize that they want to spend their time studying the lives of amphibians and reptiles. For many, the love of herpetology started early, often after the spark of seeing their first salamander or snake in the wild. My path to herpetology, particularly a love of reptiles, developed more slowly.

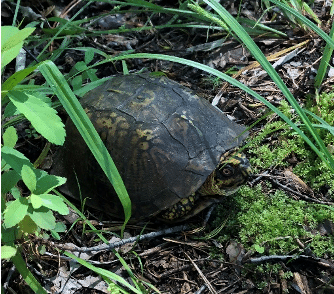

I had known for a long time that I wanted to study evolutionary biology. I’ve always loved both history and biology, and what better career than to study the history of life itself? It wasn’t until a high school job at a pet shop that I became fascinated by the diversity of colors, body types, and behaviors among amphibian and reptile species. It helped that I had grown up in Oklahoma whose East-West gradient of forest to arid habitat is home to an evolutionarily diverse array of frogs, salamanders, lizards, and snakes. Perhaps even better, as a student of the University of Oklahoma, I had access to the herpetology collection at the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Being able to freely roam the aisles of the museum collection was a dream come true.

As my education progressed from an undergraduate internship at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, to Bachelors, Master’s, and PhD degrees, so did the breadth of my research interests. Over the years, I’ve studied how different groups of skinks are related in evolutionary time and what geological processes influenced where these groups of lizards live on the planet; what ecological pressures led to the loss of limbs over 25 separate times in lizard evolutionary history; and what genetic changes underlie the evolution of live birth from egg-laying ancestors. My research has allowed me to conduct fieldwork in Australia, China, Curaçao, Mexico, and Japan, at locations ranging from deserts to remote islands. In 2015, I was honored to play a role in the training of new herpetologists by authoring four chapters on reptile fossil history, amphibian diversity and systematics, reptile diversity and systematics, and biogeography in the Herpetology textbook (4th Ed., Oxford University Press).

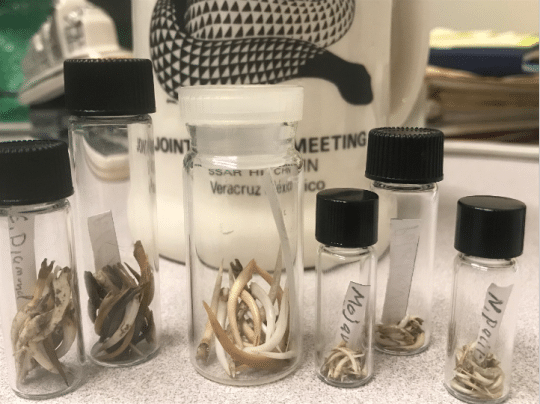

After working as a scientist in Australia for 10 years, I’m excited to join the skilled staff of the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The museum collection will allow me to continue research on the evolution of lizards, including changes to the lizard skeleton during the evolution of a snake-like body form, and the phylogeny and biogeography of skinks.

Through blogs and social media, I look forward to sharing updates on my research and the stories behind some of the 230,000 specimens of amphibians and reptiles in Carnegie Museum’s herpetology collection.

Matt Brandley is a Science Communicator and Research Associate in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is a pitfall trap (for herpetology)?

Nerding Out Over Masting, or Why Unusual Plant Reproduction Excites Animal Ecologists

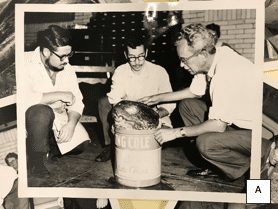

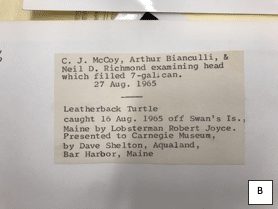

A Head Above the Rest: Unearthing the Story of Our Leatherback Sea Turtle