Last year, when Albert Kollar, Collection Manager of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, was planning for, and later recovering from, knee surgeries, it was common to hear people wish him well by saying, “You’ll be back on the outcrop soon.” In the wake of his untimely death last week, those wishes are worth examining for all they capture of Albert’s generous and long-standing sharing of geologic knowledge.

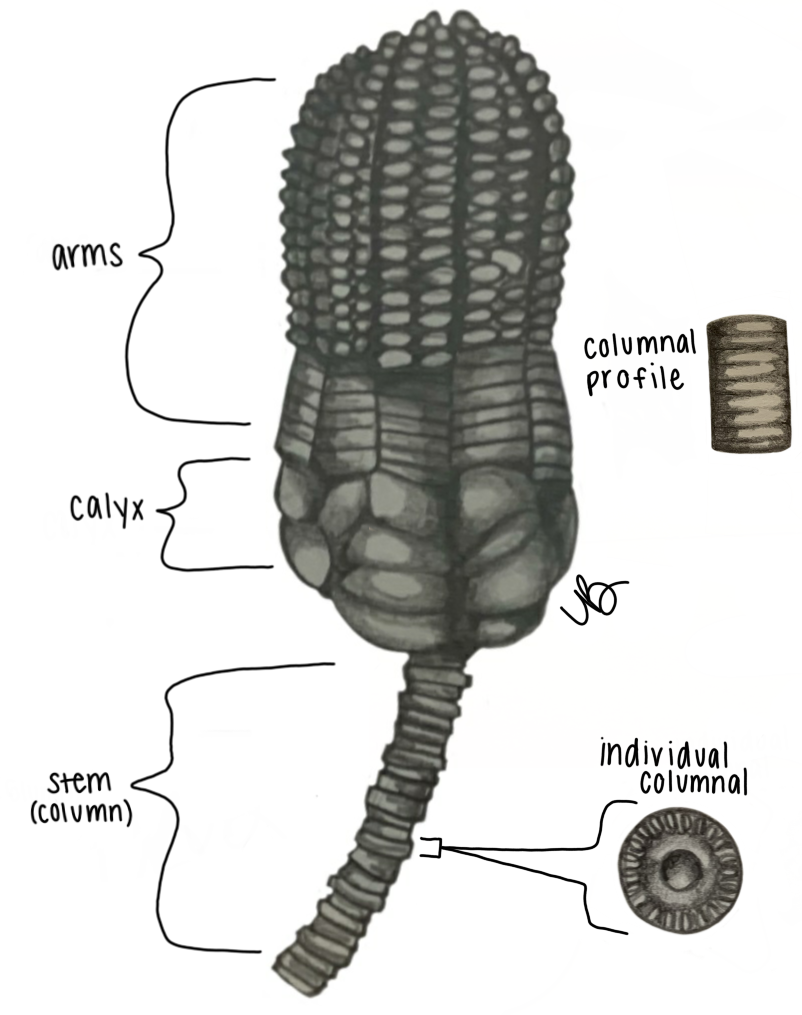

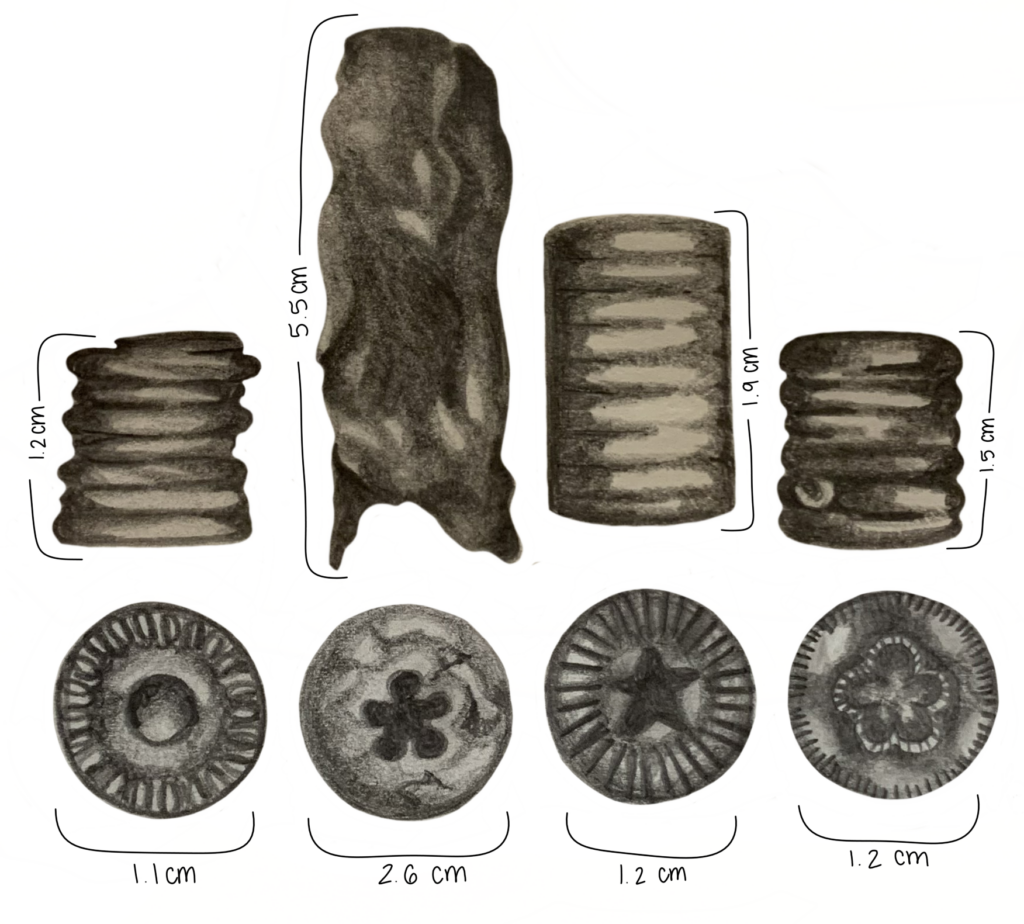

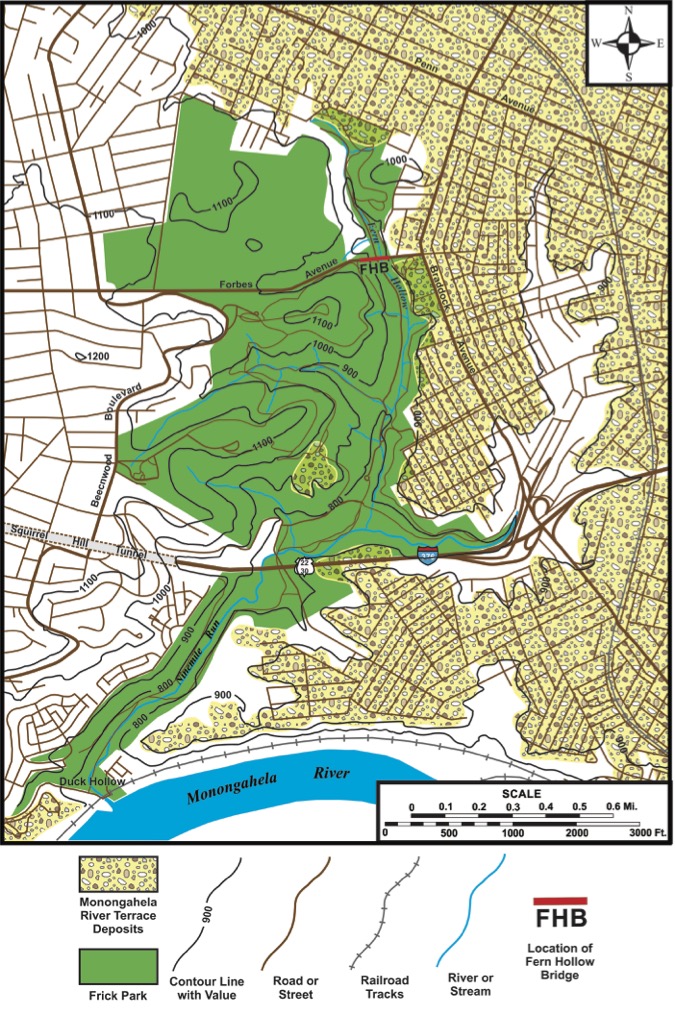

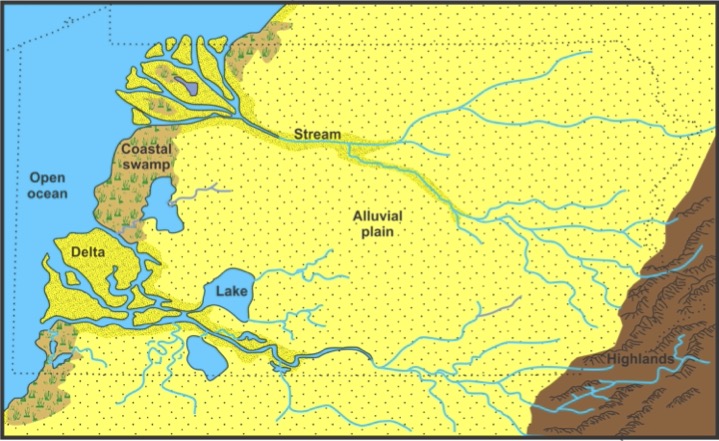

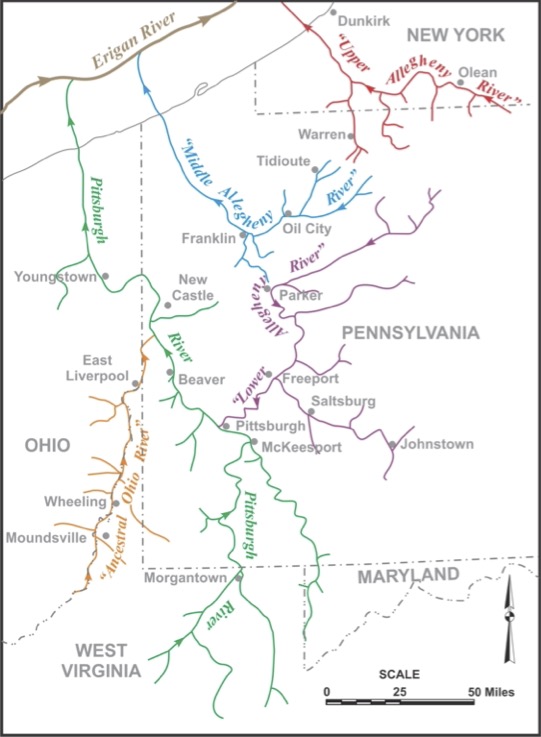

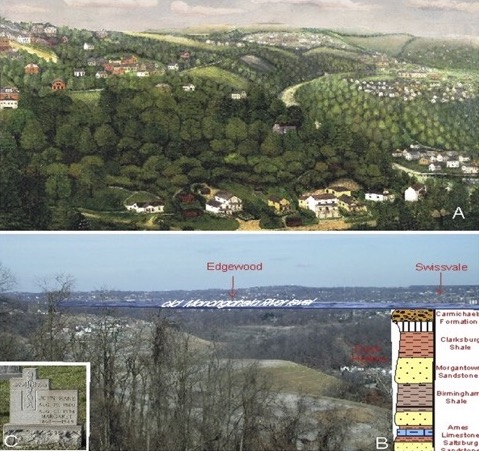

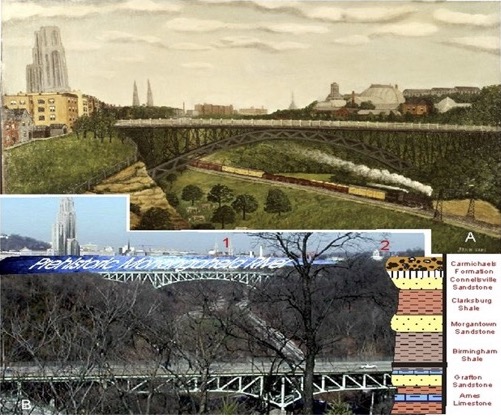

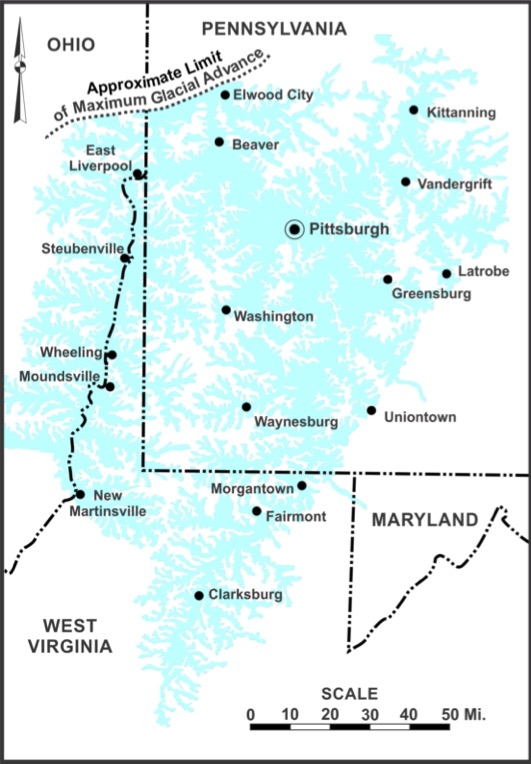

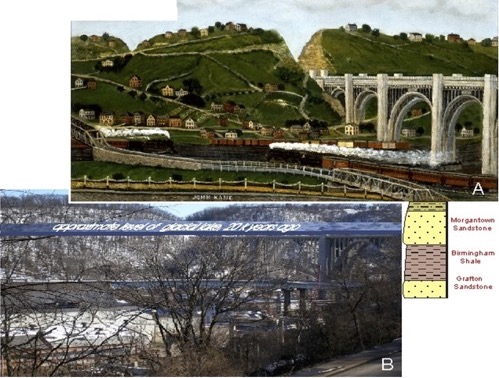

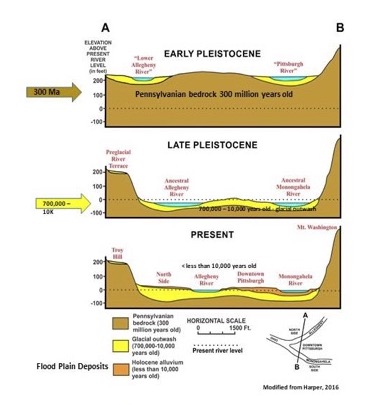

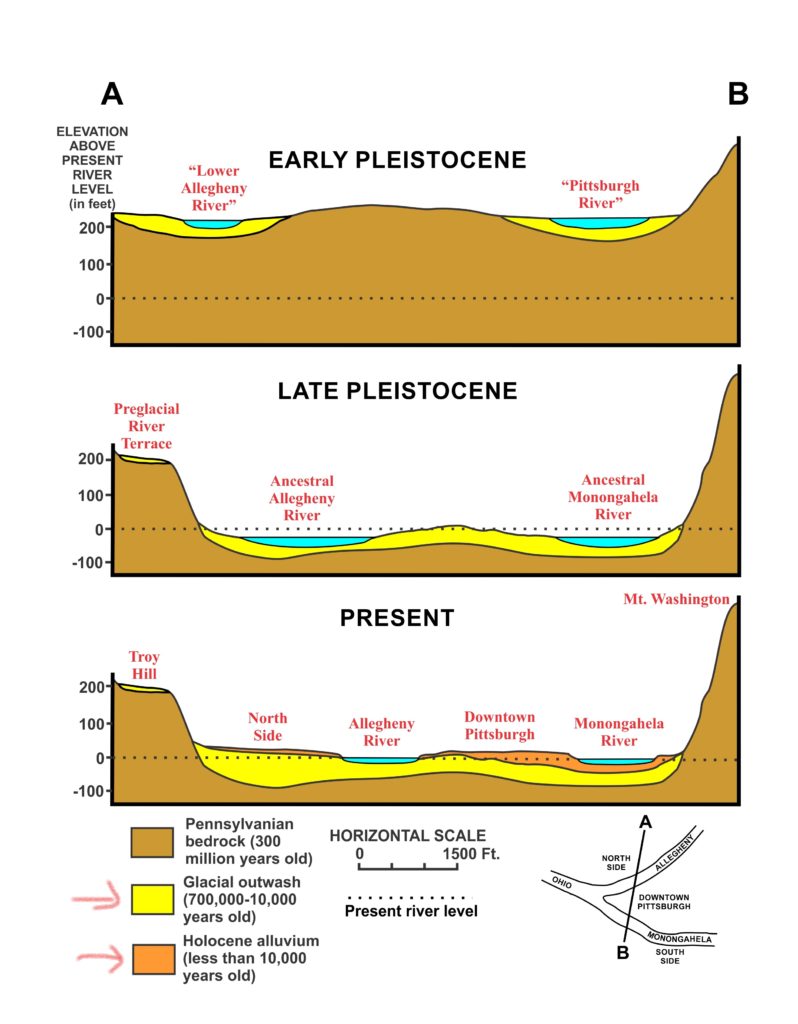

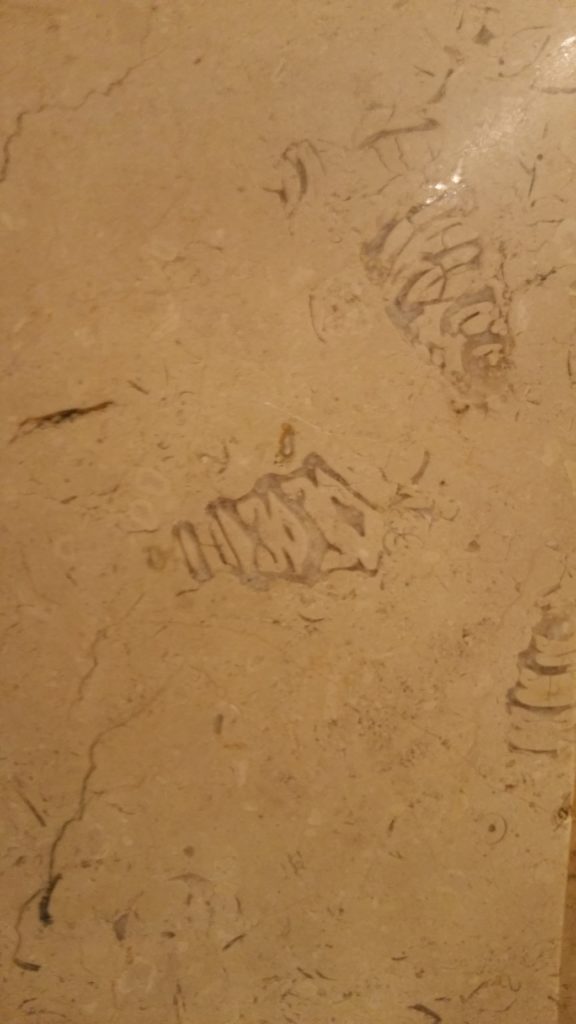

Outcrop, as anyone who participated in one of his geology-focused hikes already knows, refers to the part of a rock layer that can be seen at the Earth’s surface. Pittsburgh’s location amid a deeply eroded Appalachian plateau assures a richness of local outcrops. In river and stream cuts, natural features that in many places acquired sharper edges through the construction of road or railway terraces, multiple sedimentary units appear stacked like layers of a cake. Albert had a deep and working understanding of each of these massive rock units. He could patiently explain how their differing composition implied dramatic past changes in climate, sea level, plant cover, and even continent position.

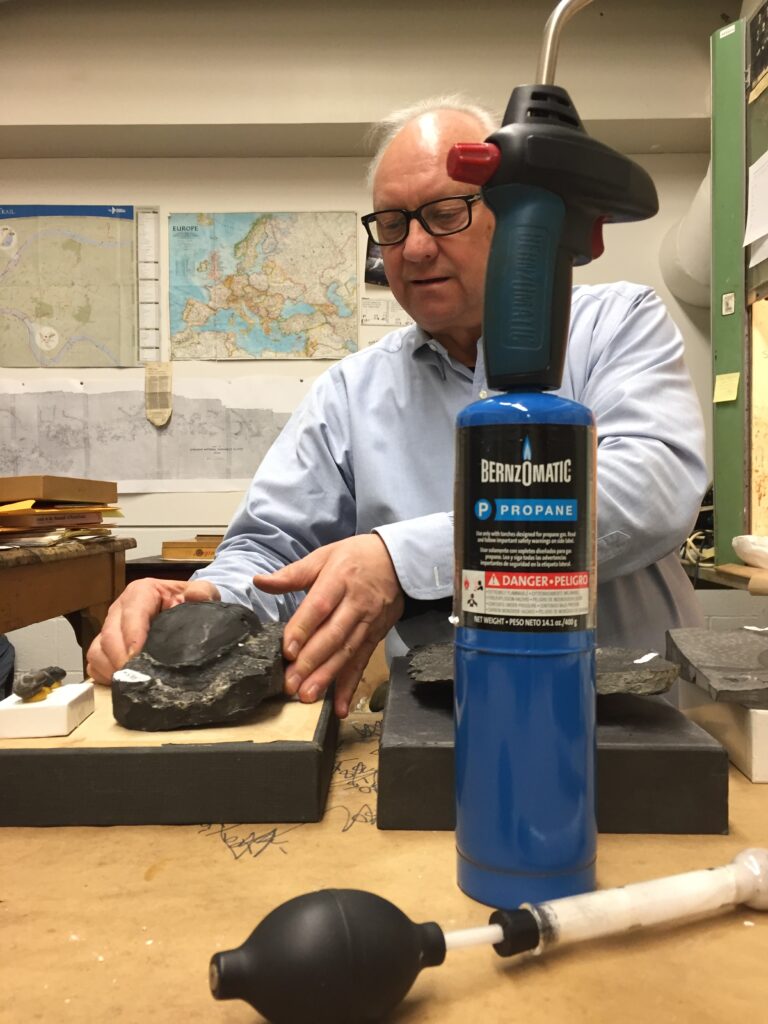

For prolonged discussions of local geology, Albert introduced audiences to several rock units prominent or economically important enough to have earned names, the Birmingham Shale, the Morgantown Sandstone, the Ames Limestone, and the Pittsburgh Coal. In explaining that every rock unit, whether it held fossils or not, contained a story about its formation, Albert would frequently distribute hand samples from these units. When the audience was a middle school class, the students could take the samples home, souvenirs not just from the museum, but from the outcrop.

Read Blog Posts by Albert D. Kollar

Meet the Mysterious Mr. Ernest Bayet

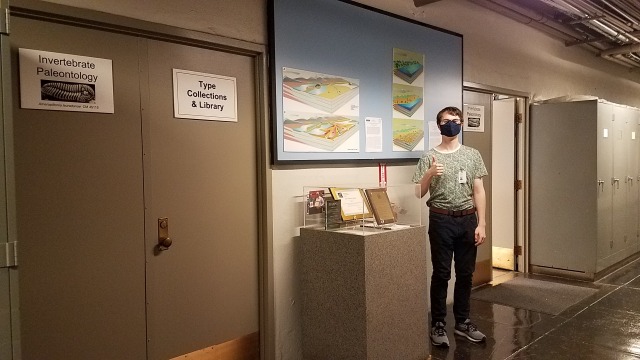

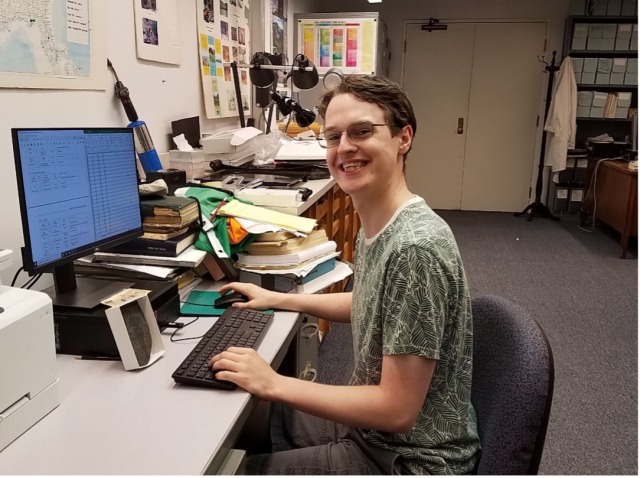

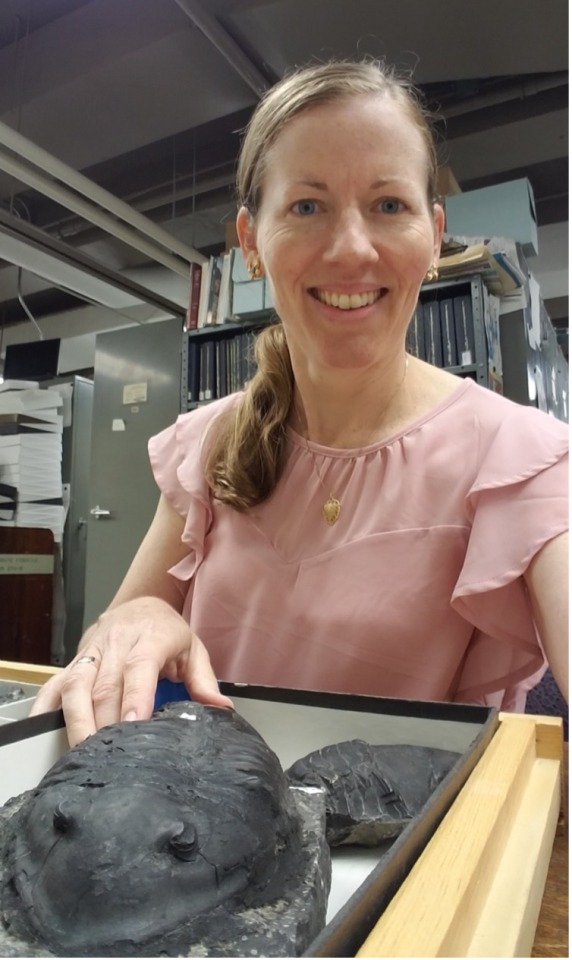

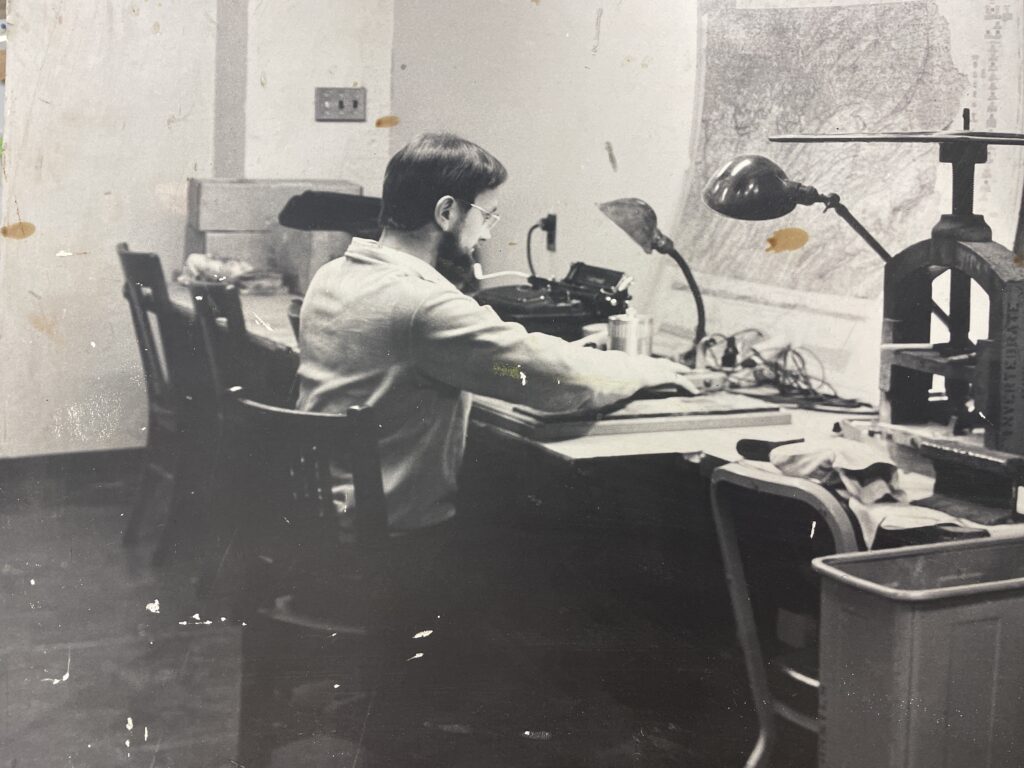

Thank you to Joann Wilson and the Invertebrate Paleontology team for the photos.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: April 16, 2024