By James Whitacre

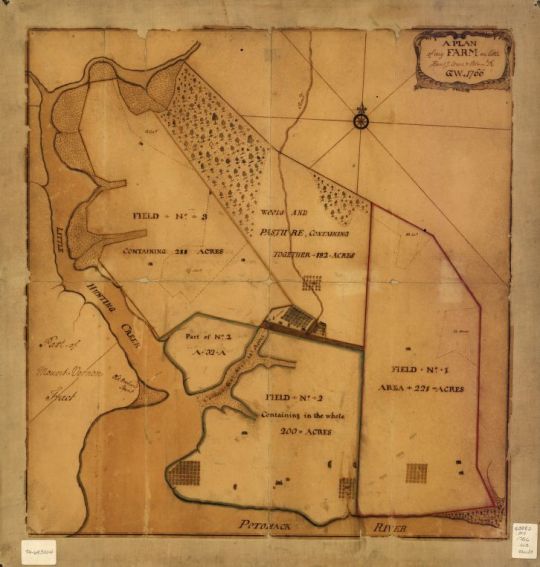

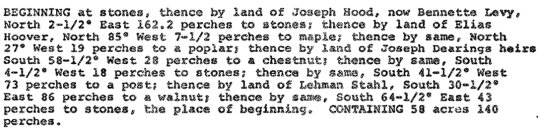

In my last post I talked about how surveyors and cartographers used chains and compasses to survey the land. They also used the system of metes and bounds to describe the data they collected, typically for land ownership purposes. At the GIS Lab at Powdermill Nature Reserve, we no longer use these techniques of old when mapping research data in the field. But with today’s advances in technology, we use much different methods and tools to collect research data.

The primary tool used today for collecting data in the field is a GPS receiver, as you might have guessed. At Powdermill, we use these devices to quickly and efficiently record latitude, longitude, and altitude. We can also couple GPS receivers with mobile apps to help us collect other non-spatial data.

To learn more about projects that use mobile apps and GPS, I recommend checking out the BirdSafe Pittsburgh program and our effort to map plastic waste.

However, you may be wondering, what exactly is GPS…and what does it actually stand for? The Global Positioning System (GPS) is operated by the US Air Force and has been around since 1978. It is a world-wide constellation of over 30 satellites that are constantly in orbit around the earth. With just four satellites in view, the location of the GPS device can be determined by using a process called trilateration, which measures the distances between multiple satellites and the device on the ground (I’m not going to get into the technical math…). GPS is also just one of a few other global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), as Russia, China, and the European Union all have operational systems as well. Many GPS devices utilize all GNSS systems.

There are many different types of GPS devices and they are generally categorized into three accuracy levels: recreational grade (accurate from 3 to within 10 meters), mapping grade (0.5 to 3 meters), or survey grade (1 millimeter to 0.5 meters). If your smartphone has GPS on it, as most do, that is considered a recreational grade GPS device. Other recreational GPS devices, such as Garmin devices, are fairly affordable and can be found at sporting goods stores. More sophisticated GPS devices for mapping and surveying are not typically found in stores and must be ordered from specialty vendors.

The above image shows the different devices the GIS Lab has used over the years. At Powdermill, we use mapping grade GPS devices most often, as represented by the four devices on the right in the image above, but we also use recreational GPS devices and GPS-enabled mobile devices, which are the four devices on the left. We no longer use the top row of devices as the devices on the bottom row are newer technology that vastly outperform the older devices. The need for survey grade GPS devices is not typically needed for research at Powdermill, as one to three meters of accuracy is usually good enough for most ecological and field biology research.

By collecting research data with geographic information collected from GPS, we can analyze ecological phenomena in space, which allows us to discover much more about plant and animal communities. For example, we have used GPS to collect where trees are in addition to the species and size of the trunk. When we analyzed the distribution of our trees, we learned that red maples tend to grow on south facing slopes, while sugar maples tend to grow on north facing slopes. This information could impact future decisions for our forest management. Therefore, it is essential that we think spatially about our research!

James Whitacre is the GIS Research Scientist for Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where he primarily manages the GIS Lab at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the Museum’s environmental research center. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.