Researchers in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s (CMNH) Section of Amphibians and Reptiles celebrate five new species described in 2023. Associate Curator Dr. Jennifer Sheridan and an international research team describe four new species of Southeast Asian frogs in the genus Amolops in the journal Vertebrate Zoology. Collection Manager Mariana Marques and international colleagues describe a new species of legless skink (small lizard) from Angola in the African Journal of Herpetology. Both museum researchers are lead authors of their respective studies.

Marques and Sheridan’s discoveries took place 6,000 miles apart on different continents, yet both provide new scientific insights about their respective regions. In the face of a worldwide decline in biodiversity due to human impact, the documentation of new-to-science species fills vital knowledge gaps for a better understanding of ecosystem health. The better scientists can document biodiversity, the better they understand the effects of biodiversity loss and how to identify future conservation goals.

“Publishing five new species within less than three weeks is exciting for us and the museum,” said Sheridan. “Both discoveries required a combination of field work and research back at the museum. Mariana knew in the field that she had likely encountered an undescribed species, while in my case, these frogs were labeled as Amolops cremnobatus in the field because that’s what they looked like. Years later, once we started looking closely at numerous individuals collected by many researchers, we began to fully realize the diversity hidden in the Amolops genus.”

Sheridan and researchers from Laos and North Carolina hypothesized that the Lao torrent frog Amolops cremnobatus, first described in 1998, is actually five species in the genus Amolops based on mitochondrial DNA analysis of specimens from Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand. Their paper in Vertebrate Zoology describes the four new species Amolops tanfuilianae, Amolops kottelati, Amolops sengae, and Amolops attiguus.

“These are extremely cryptic species,” said Sheridan. “So, determining the differences is not as simple as ‘specimen A has different coloration than cremnobatus’ or anything like that.” The visual differences between adult specimens were small and included varied finger lengths and the number of vomerine teeth (used to capture and hold prey). Tadpole morphology (size, shape, and structure) was key; even though adults are collected more often than tadpoles for scientific study, tadpole information is important. Body length, presence or absence of glands, and other physical features in tadpoles provided crucial data to differentiate the new Amolops species. Molecular data including mtDNA and nuDNA analysis also revealed differences the research team needed to describe the four new species. The team recognizes that continued research in Thailand may reveal additional species.

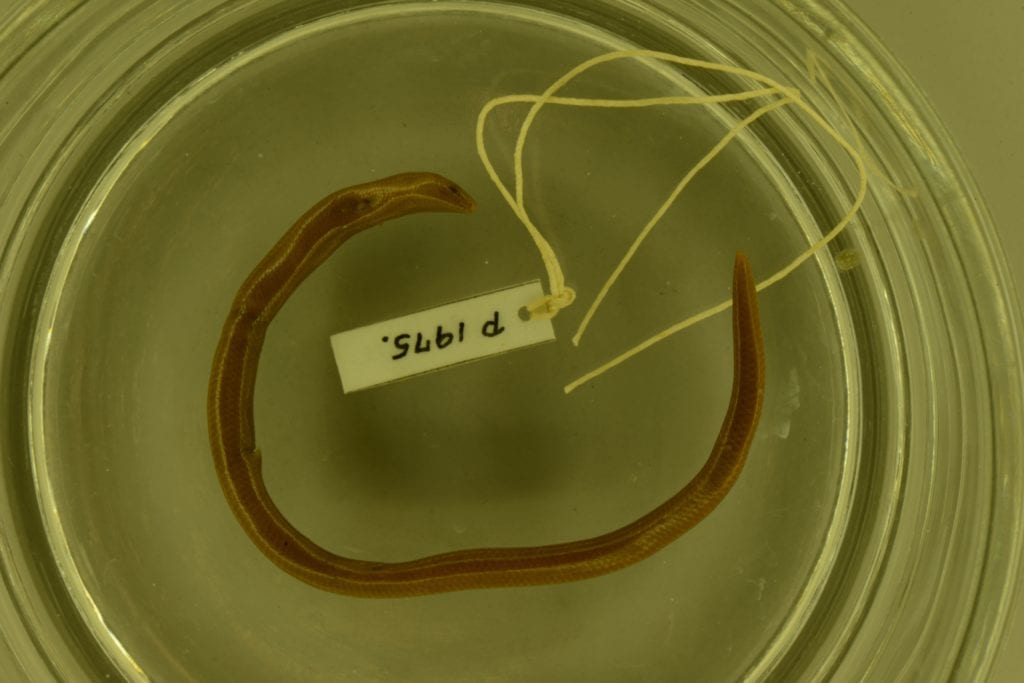

Meanwhile, Marques and an international team of researchers discovered the skink Acontias mukwando on Serra da Neve, an inselberg, or isolated, rocky outcrop, in Angola, one of the most ecologically diverse countries in Africa. Moveable eyelids and distinct coloration distinguish the new species, Acontias mukwando, from other species in the genus Acontias. The research team chose the species name in honor of the local Mukwando tribe to recognize their support and friendship during field work.

Both Sheridan and Marques used specimens from the collections of multiple other museums to fully determine how these newly described species are unique, and how they relate to their closest relatives. They relied on collections made by numerous researchers from multiple countries, highlighting the value of collaborative museum networks for understanding global biodiversity.

“Finding a specimen like Acontias is always exciting,” said Marques. “These animals spend most of their time under rocks and foliage, and they are not usually seen by people. There is so much we don’t know about them. Discovering that a member of a little-known group occurs on top of an equally obscure mountain was such an exciting mystery to solve. It was one of those rare ‘wow’ moments in your career as a scientist! My goal is to provide a solid and scientific overview of the fauna occurring in Serra da Neve, in order to support its conservation and contribute to the understanding of its rare biodiversity.”

CMNH’s Section of Amphibians and Reptiles maintains a collection of more than 230,000 specimens and ranks as the ninth largest amphibian and reptile collection in the United States. It includes 156 holotypes, the single type specimens upon which the descriptions and names of their respective species are based.