by the Section of Anthropology and Archaeology Staff and Volunteers

With the pink wave that is Barbie sweeping the theaters, we thought it would be a good opportunity to spotlight our doll collection. The Anthropology collection at CMNH holds more than three thousand dolls and it is our pleasure to take care of them. Historically and anthropologically speaking, dolls have always served cultural, spiritual, and societal purposes. Whether for entertainment, religion, or education, they can be found all over the world and have been around for thousands of years.

Barbie

“Hi Barbie! Until recently, our doll collection lacked any traces of Barbie. Then a close friend of the Section of Anthropology was kind enough to not only donate their beloved original doll but also the clothing that they had sewn for her. Barbie and Ken, as an astronaut, a rock star, a pregnant Midge, beach, or any other iteration, have impacted the lives of millions. Sadly, there has not been an archaeologist Barbie but the best part about playing with dolls is that I can easily pretend that the paleontologist version is diligently studying human culture instead of dinosaurs (Sorry, Dr. Lamanna).

Individuality has always been important to me, so I have always been the biggest fan of Weird Barbie, upon whom I did my fair share of hair cutting and marker tattooing. And while we have only one Barbie at CMNH, we have plenty of other dolls in the collection that our staff and volunteers have chosen to write about. Please enjoy some of our favorites.” –Amy Covell-Murthy, Archaeology Collection Manager and Head of the Section of Anthropology

Miss Kochi the Friendship Doll

On January 14, 1929, complete with passport, steamer ticket, and a trunk full of accessories, Miss Kochi the friendship doll arrived in Pittsburgh to her new home at the museum. Representing the children of Kochi, the southernmost prefecture on the island of Shikoku in Japan, Miss Kochi crossed the Pacific with 57 other friendship dolls who went to various cities within the United States.

Created as part of a doll exchange program between the children of Japan and the U.S., Miss Kochi and her sister dolls were lovingly made with the hope of promoting peace between the two countries in the years leading up to World War II. Crafted by some of the most respected doll makers in Japan, the ambassador dolls, as they were also known, are all 85cm high. They have moveable arms and legs and real human hair. Each is dressed in a colorful kimono made of pure silk and accompanied by lacquered tea sets, furniture, and other accessories used in the celebration of Hinamatsuri, or Doll’s Day. Miss Kochi is dressed in a beautiful, embroidered, emerald green kimono with a red sash.

“Miss Kochi is one of my favorite dolls in the collection because I love all the care and detail that was put into her outfit and tiny accessories. Additionally, the message of friendship and kindness that motivated her creation and eventual journey to Pittsburgh is charming and inspiring.” –Kristina Gaugler, Anthropology Collection Manager

Eagle Kachina

The Eagle Kachina holds special significance to both the Hopi and Zuni people, representing important spiritual and cultural aspects in their respective traditions.

To the Hopi people, the Eagle Kachina is considered a powerful and sacred being. It is associated with spiritual strength, protection, and a close connection to the divine. The eagle is revered for its ability to soar high in the sky, reaching great heights, and is seen as a messenger between the earthly world and the spiritual realms. During Hopi Kachina ceremonies, the Eagle Kachina is often portrayed by a dancer wearing an elaborate costume and a mask representing the eagle’s features. The dancer embodies the spirit of the Eagle Kachina and plays a significant role in ceremonial dances.

For the Zuni people, the Eagle Kachina, also known as “Ko’kko,” holds similar importance. The Zuni Eagle Kachina represents the embodiment of the eagle spirit and is venerated for its connection to the heavens and its role as a messenger to the gods. The Zuni people view the Eagle Kachina as a symbol of power, courage, and wisdom, and it plays a crucial role in their rituals and religious practices. Like the Hopi, the Zuni also create intricate Kachina dolls, including the Eagle Kachina, as sacred objects representing the spirits and their significance in Zuni culture.

“I like the Eagle Kachina doll as it signifies all that is important to me as it is to the Hopi and Zuni, the spiritual connection to the natural world.”—Jim Barno, Archaeology Volunteer

Calabash Gourd Doll

To make this doll, a Tonga woman or girl from a village near Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe, would have filled calabash gourds with sand, seeds, or stone, and covered the gourds with mud, dung, and leaves, before decorating them with strands of beads. Dolls like this one were made by or given to Tonga girls around the ages of 10 to 13, as they approached puberty. The doll came into CMNH’s collection in 1967 as one of many objects from the Tonga people obtained through trade by Terence Coffin-Grey, a taxidermist who worked in natural history museums in Zimbabwe and the U.S., including at CMNH. This doll’s “hairstyle,” with tight balls made of mud and strands of beads, resembles that of some Tonga women of the time, based on photographs shared with CMNH by Coffin-Grey. CMNH has several other similar dolls of different sizes, shapes, and decorations, including some with fabric skirts.

“I chose this doll based on the recommendation of Amy Covell-Murthy and was immediately charmed and intrigued when I saw it. When I held it, I was struck by the weight of it, and I loved learning about this practice of doll-making shared between women and girls in a matrilineal society.” –Deirdre M. Smith, Assistant Curator

Talash Doll

We are all a part of nature. Our ancestors created dolls for children using the natural materials around themselves. The tradition of making dolls from talash, the leaves wrapped around a corn cob, dates back many generations.

Talash is a very interesting material that is easy to work with, and the products made from it are very warm and beautiful. The husks of the corn would be removed in the fall after harvesting the corn. They would then be dried and stored in a dry place. The leaves come in different colors and shades, from white to brown. If necessary, the leaves could also be painted, sometimes with dyes made of onion peel or food coloring. To begin weaving, the middle leaves of cobs are often preferred for their strength and flexibility so as not to tear. The husks are also moistened with water to help give them more elasticity. The length of the strip up to 1 cm is in the middle. Strips that are uneven or ripped would be discarded.

This doll is of boys riding a pig, which highlights ordinary country life in a European village. Eastern Europe has a lot of rivers such as the Danube, Vistula, Dnipro, and others. The territory near the rivers is very large, and kids would help relatives graze pigs on these meadows, while also occasionally playing with them.

“This doll showed me how people create interesting toys with simple natural things. This is part of our deep roots and traditions in Eastern Europe. I also like the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen called Swineherdand (The Swineherd), and for me this doll is reminiscent of that story.”—Lidiia Zadorozhna Ruban, Anthropology Library Volunteer

Balinese Tjili Doll

This Balinese Tjili doll came to be a part of the Carnegie collection in 1980 through the donation of Dr. Betty J. Meggers, an international doll collector. Made in the image of Dewi Sri, Indonesia’s goddess of rice and fertility, figures like this doll symbolize fruitfulness and good harvests.

“This doll caught my attention because of her intricate woven design and large, fan-like headdress that radiates like a setting sun. I believe her story shows how dolls can serve so many purposes and are beloved by different cultures all around the world.”—Lily Heistand, Anthropology Volunteer

Folklórico Dancer

This doll is a folklórico dancer! Made in Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, this doll joined the museum’s collection as a donation in March of 1950. She is made of wool and cotton and has black braids (trenzas folklóricas), a white embroidered blouse (blusa bordada), and a sequined red and green skirt (china poblana). All these components make her instantly recognizable as a ballet folklórico dancer (folk dancer). Her skirt is designed after one of the most recognizable traditional styles of dress in Mexico, la china poblana. China poblana skirts tend to be heavy as they are made with layers of embroidery using sequins and beads to depict the Mexican coat of arms of the eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its mouth. Historically, this style of dress was popular in the state of Puebla, but nowadays it is typically worn by dancers when performing El Jarabe Tapatío, which is a dance from the state of Jalisco and México’s national dance.

“I chose this doll because she beautifully represents my culture and my family. My abuelita embroidered a china poblana skirt that my mom performed in, and years later I also danced in it. This doll represents a tradition that ties together three generations of women in my family and the beauty of our cultural traditions.”—Matí Castillo, Fine Fellow, University of Pittsburgh

Angel of Mercy

This doll is an “Angel of Mercy.” This nickname was affectionately given to the unsung heroes of the Great War, the nursing sisters, who worked long gruesome hours and attended to the needs of injured soldiers. The casualties of World War I were extensive, but the nurses worked tirelessly to aid in wound cleaning, bacterial-growth prevention, and even assist in emergency surgeries all while fearing for their own wellbeing. This doll was donated in 1918 by Mrs. Virginia Hayes Osburn along with many other ‘war woolies.’ These war woolies were dolls that were made by the Canadian Red Cross Vancouver during the Great War. According to the British Red Cross Museum and Archive, these “wooly” dolls were crafted by the Vancouver Prisoners of War Branch of the Canadian Red Cross to fundraise during World War I.

“I chose this Canadian Red Cross Nurse doll because though she is miniature, her face was expressive, and I wanted to research more about her because the other war woolies she was housed with were depictions of English monarchs; I wanted to tell her story as an unsung female hero of the Great War.”—Caitlin Erb, St. Laurance University Post-Baccalaureate Intern

A. Marque Character Doll

Fashion icon Isabeau de Bavière is one of the five queens that made their way to Carnegie Museum in 1916. After seeing a French character doll exhibit in the Metropolitan Museum in 1915, Herbert DuPuy wrote to the Director of Carnegie Museum, Dr. W.H. Holland, suggesting the addition of such wonderfully crafted dolls into Carnegie’s collection. Less than a year later, five A. Marque and thirty-five other character dolls from the Paris doll company S.F.B.J were part of the museum.

Isabeau is a rare A. Marque bisque doll, fashioned after the queen of France reigning from 1371-1435, and dressed by the famous couture artist Margaine Lacroix. She gives a glimpse into the accurate historical fashion of the late fifteenth-century nobility. From her undergarments to the recognizable pointed hennin hat of the Medieval period, Isabeau directly copies portraits of the queen.

“I chose this wonderful doll because of her fascinating history and design; the A. Marque dolls are some of the rarest dolls the museum currently owns, and one of my favorites to admire.”—Elizabeth R. Dragus, Anthropology Volunteer

Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Woman

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Woman doll was donated by James B. Richardson III, (Carnegie Museum Anthropology Curator Emeritus), in memory of his mother Miriam Davenport Richardson. The doll was made by Debra Bell of the Nimpkish Band of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Nation located in Alert Bay, British Columbia. Debra Bell is one of a very few Northwest Coast Indigenous female doll makers. On a research expedition for Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Alcoa Hall James Richardson purchased this doll in 1992.

Embroidered on the wool felt blanket is a “Tree of Life” design, symbolic of the coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwest which are full of Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, yellow cedar, and western red cedar. Collectively, these tree species are the sustenance of Indigenous people, providing lumber for homes, fire for heat, homes for birds, and shelter for mammals. They also sustain waterways and breathe oxygen into the air.

A plaited cedar bark wreath adorns the doll’s head. Yellow cedar is considered the finest cedar in the region and used in traditional ceremonial objects. The tree is found in deep porous soil on slopes, around lakesides, and within estuaries. The oral history of yellow cedar in Northwest cultures derives from this story; “Raven asked a few young women what forest creature they were afraid of. The women replied, ’none.’ Raven then asked if the women were afraid of owls. The women exclaimed, ‘Yes, [they] were terrified of owls!’ Raven (being known as a trickster) hid in some bushes making owl sounds. The young women went running up the slopes. That is why yellow cedar is only found on slopes.”

Most Northwest tribes believe humans can transform into animals and back again. The red felt killer whale applique embroidered with pairs of amber glass seed beads on the doll’s dress symbolizes one of these stories of human transformation. The killer whale is known as Natsilane and believed to be part of Earth’s creation. Natsilane was drowned by his brothers who wanted control of the world. Left to die, Natsilane was rescued by a sea otter and restored to his legitimate place as leader. Natsilane helped the sea otters find the safest hunting waters in return for saving his life.

The Northwest Coastal native Americans have a fiercely independent culture steeped in storytelling and deeply rooted in the infinite wisdom of nature. All these attributes can be noted when viewing the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Woman doll.

“I was taken by this doll’s face staring out from her collection box with blue glass paperweight eyes and painted eyelashes for numerous reasons. I had lived in Oregon and Washington states for a few years and was always caught by the breathtaking beauty of shorelines and forests. The doll reminded me of that majestic landscape in her blue wool button blanket. Although the button blanket did not appear in the Northwest culture until colonization, the deep color of the wool is reminiscent of the sea and sky in the area.”—Georgia Feild, Archaeology Volunteer and Museum Educator II

Meskwaki Man

“My favorite doll in the collection is the Meskwaki man in traditional clothing, probably made in the 1920s. Part of what caught my eye was the attention to detail.

The man’s head, moccasins, and bag are made from brain-tanned deerskin, with simplified traditional sewn beadwork designs. His beaded headband is loom-woven, and his body is sewn of cotton muslin.

He has a satin shirt with silk ribbons [like the ribbon shirts worn today], and wool trousers under his beaded aprons. Originally, men wore loincloths, beaded for special occasions, which evolved into aprons in the last half of the 19th century as men started wearing trousers.

My favorite part of the outfit is the finger-woven sash. Finger-weaving is a form of oblique interlacing, a sort of wide, flat braid. I was first introduced to finger-weaving in the late 1960s, when I made finger-woven sashes in my dorm room for all my hippie college friends. Finger-weaving was and is found all over eastern North America, where the technique is used to create sash belts, garters, and bags. Colors, designs, and techniques differ in the different cultural areas. The people in the upper Midwest made wide bands which the men wrapped around their heads like turbans and adorned with feathers. [Southeastern men also wore turbans with feathers but preferred to use silk shawls.]

The earliest recorded piece extant of the technique comes from the Craig Mound in Spiro, Oklahoma, and dates to around 850-1450CE. It is currently in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.”—Deborah Harding, Anthropology Collection Manager Emeritus

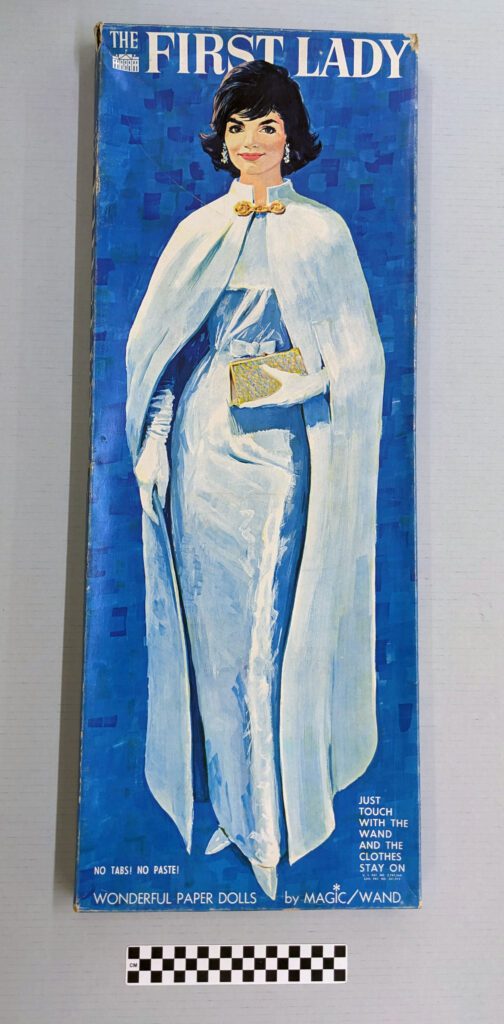

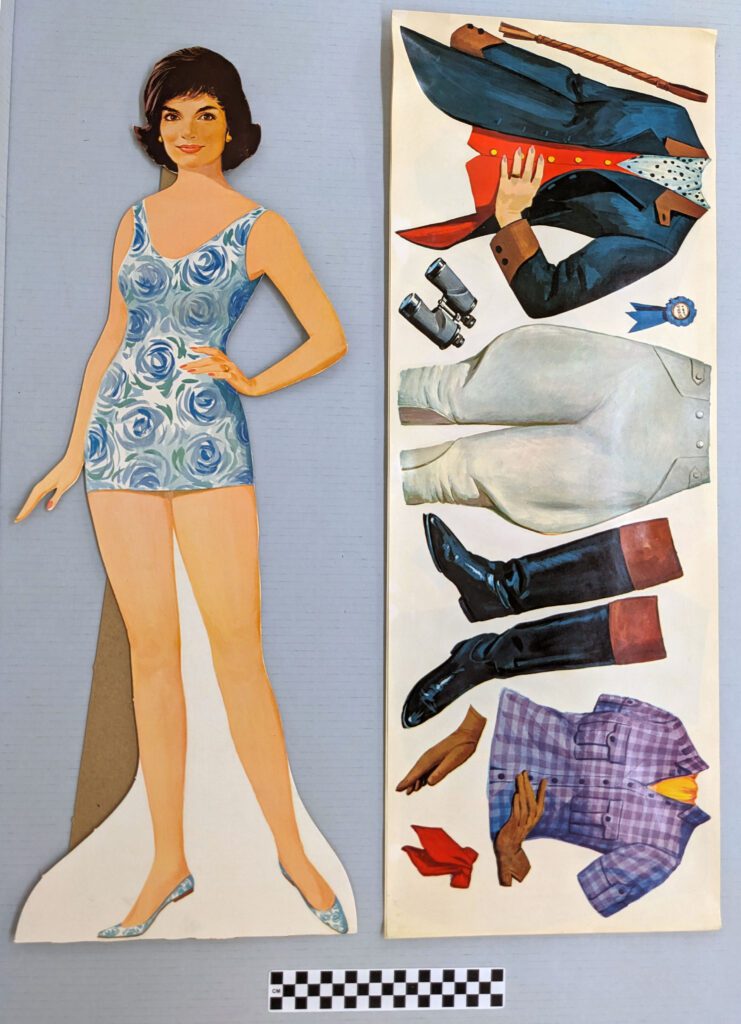

First Lady Paper Doll

This supersized paper doll depicts fashion icon and First Lady Jackie O. It was donated by Dr. Betty Meggers. She and her mother collected dolls from around the world beginning at least as early as the 1930s. She donated more than 1,000 to the museum. As you can see from the box, this paper doll used a “magic wand” to keep the clothes on the doll – no tape or paste required!

“I used to love dressing, playing with, and making paper dolls. I chose paper dolls because they are universally accessible, all it takes to create one is paper and imagination. Manufactured paper dolls come from all over the world and provide people with the opportunity to see, play with, and learn about all different types of people, jobs, and cultures. They are also great for kids like me, who really love fashion. My grandma Kelley had a wonderful set of dolls and paper dolls that I would play with whenever I went to her house. I love the freedom of being able to dress the dolls however I wanted, to change their hair and outfits, and even to design new outfits of my own.”—Lisa Haney, Assistant Curator, Egypt on the Nile

Tibetan Buddhist Doll

Yamantaka, “Destroyer of the God of Death.” Not exactly a character you’d think of making into a doll to be used as a plaything, something to cuddle, or as a tool to teach children how to care for babies. However, to practitioners and students of Tibetan Buddhism, this type of doll serves as a visual reminder of the history, values, and lessons that are core to the culture. Although doll-making isn’t a traditional art form in Tibet, Yamantaka shows up in many other visual forms of Tibetan Buddhist art. This unusual doll from the museum’s collection showcases some handicrafts that aretraditional to the culture such as garment-making, tapestry, sculpting, painting, and beading.

Who was Yamantaka and why make a doll of him? The short version of the story is that there was a monk who became wrathful and took on the form of an enraged water buffalo. He caused death and destruction all over Tibet and became known as Yama, The God of Death. The people prayed for someone to stop him and restore peace. A bodhisattva (a deity who helps people) transformed himself into the form of an even bigger, scarier water buffalo to find Yama and convince him to change his ways. By stopping the God of Death, the bodhisattva became known as Yamantaka, the Destroyer of the God of Death. Yamantaka showed mercy on the repentant monk and reminded him to live by the Buddhist principles of compassion, self-control, detachment from ego, and wisdom-seeking. By exemplifying these qualities and restoring peace, Yamantaka was regarded as a protector of Buddhism. A legendary superhero. Someone deserving to have a doll, or rather an action figure, made in his likeness for future generations to aspire to.

“This doll stood out to me at first glance because of its vivid, striking visual impact. Then, as you let your eyes coast over all the details, you become aware that it is just as nuanced as it is bold. For example, the subtle metallic tips on the flames are equally important as the formidable facial expression. For every single thing you see there’s more to the story, and it’s probably not what you’d expect. The doll’s purpose was to preserve, teach, and remind people of the culture. Indeed, it inspired me to seek out and learn about the significance of Yamantaka’s story and, by extension, Tibetan Buddhist traditions and beliefs.” -Jillian Hanna, Anthropology Volunteer

Bye Barbie!

Many of our dolls have been used to augment traveling exhibitions and have served as research subjects. It is our great honor to care for them and learn from them. The next time you visit the museum, don’t forget to stop by the Alcoa Hall of American Indians and look for our dolls that are currently on exhibit.

Related Content

Bringing a Little O-Gah-Pah to Pittsburgh

Sources Consulted

CMNH accession records

Transformations: Salmon, Bear, Raven, and Humans

Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

The Rise of Yamantaka, Destroyer of the Lord of Death

British Red Cross. (2010). Small woolen doll dressed in French military uniform. British Red Cross collection online. https://museumandarchives.redcross.org.uk/objects/8999

Flexon M. Mizinga, “Marriage and Bridewealth in a Matrilineal Society: The Case of the Tonga of Southern Zambia, 1900-1995,” African Economic History 28 (2000): 53-87.

Malaika P. Yanou, Mirjam Ros-Tonen, James Reed, and Terry Sunderland, “Local knowledge and practices among Tonga people in Zambia and Zimbabwe: A review,” Environmental Science & Policy 142 (April 2023): 68-78.

Wilfrid Laurier University. (2015). Angels of Mercy: Canadian Nurses in the Great War. Youtube. Retrieved July 27th, 2023. from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zITLh6jPYY

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Covell-Murthy, Amy; Gaugler, Kristina; Barno, Jim; Smith, Deirdre M.; Zadorozhna Ruban, Lidiia; Heistand, Lily; Castillo, Matí; Erb, Caitlin; Dragus, Elizabeth R.; Feild, Georgia; Harding, Deborah; Haney, Lisa; Hanna, JillianPublication date: August 4, 2023