by Mason Heberling

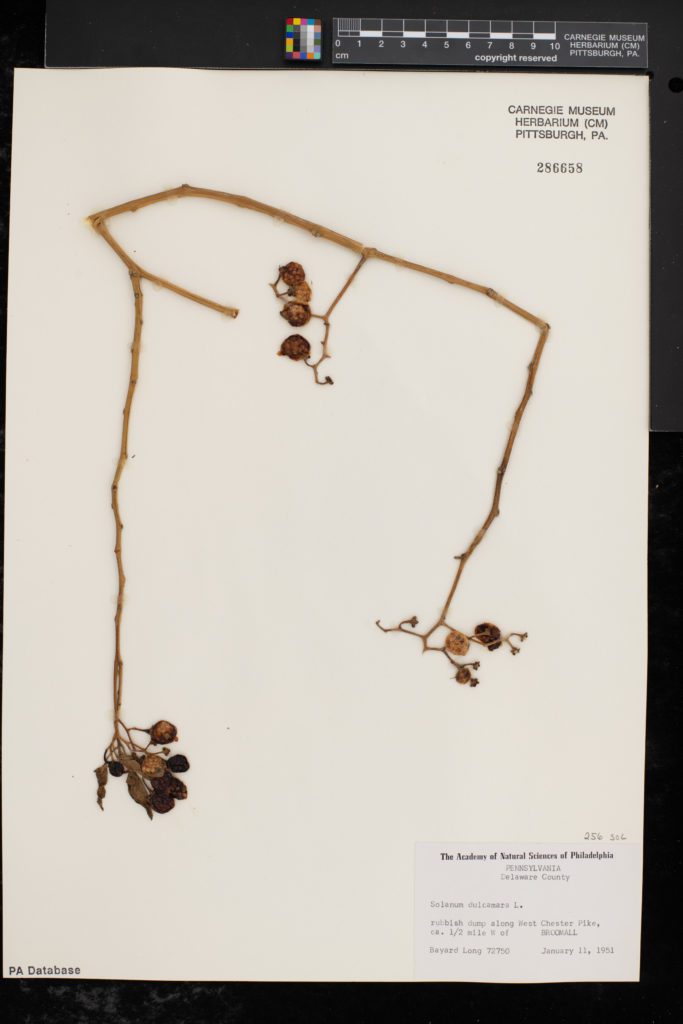

Leaves are gone, but fruits hang on

This specimen of bittersweet (Solanum dulcamara) was collected by Bayard Long on January 11, 1951 in a “rubbish dump” on West Chester Pike, near Broomall, Pennsylvania (outside of Philadelphia). Bayard Long (1885-1969) was a Philadelphia-area botanist and an active member of the Philadelphia Botanical Club (founded in 1891 and still an active organization). He was a prolific collector and for 56 years served as Curator of the Club’s Local Herbarium, which is housed at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) is in an herbaceous vine in the potato or nightshade family (Solanaceae), not to be confused with the similarly named Asian bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), which is also a woody vine in the staff vine or bittersweet family (Celastraceae).

Bittersweet is an invasive species, introduced from its native range in Europe and Asia as early as the 1800s. It is common to see climbing along fences in urban areas and elsewhere across North America.

In the winter, its fleshy red berries are commonly still attached to the vines, long after the leaves are gone.

Find this specimen of bittersweet.

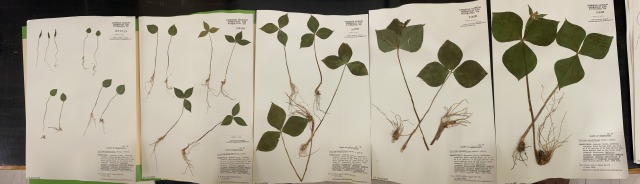

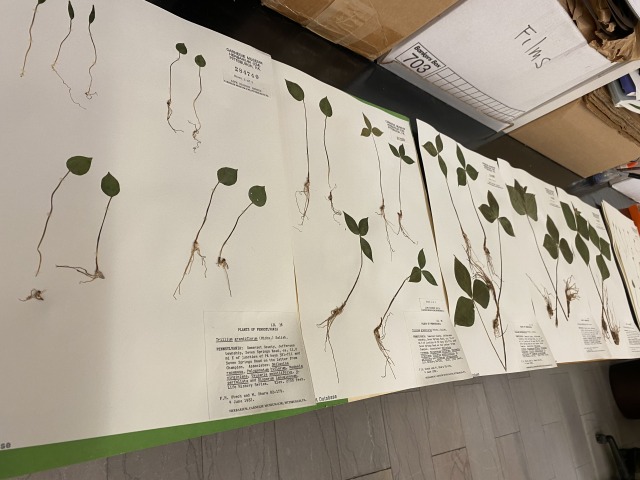

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

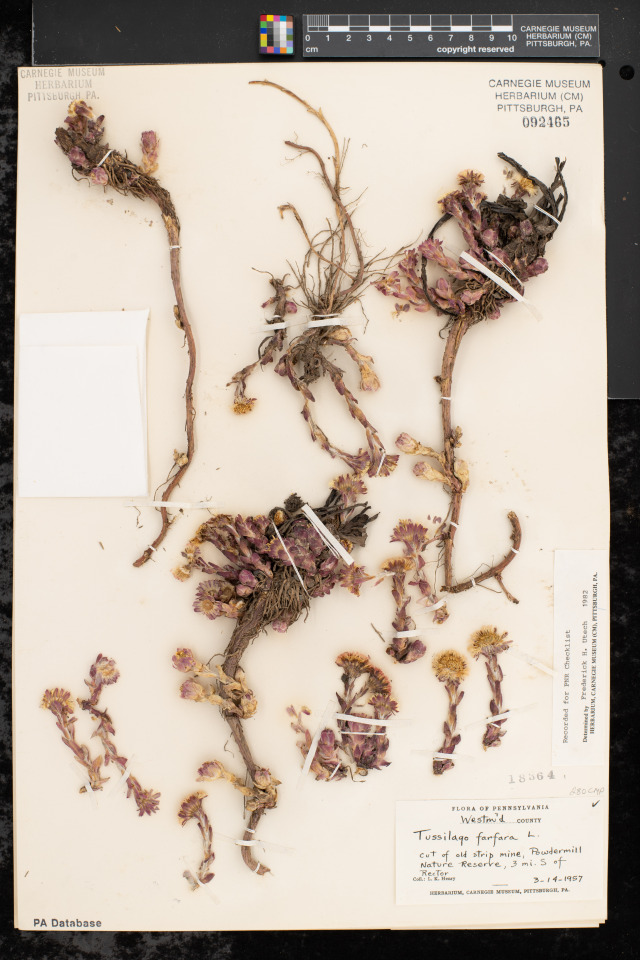

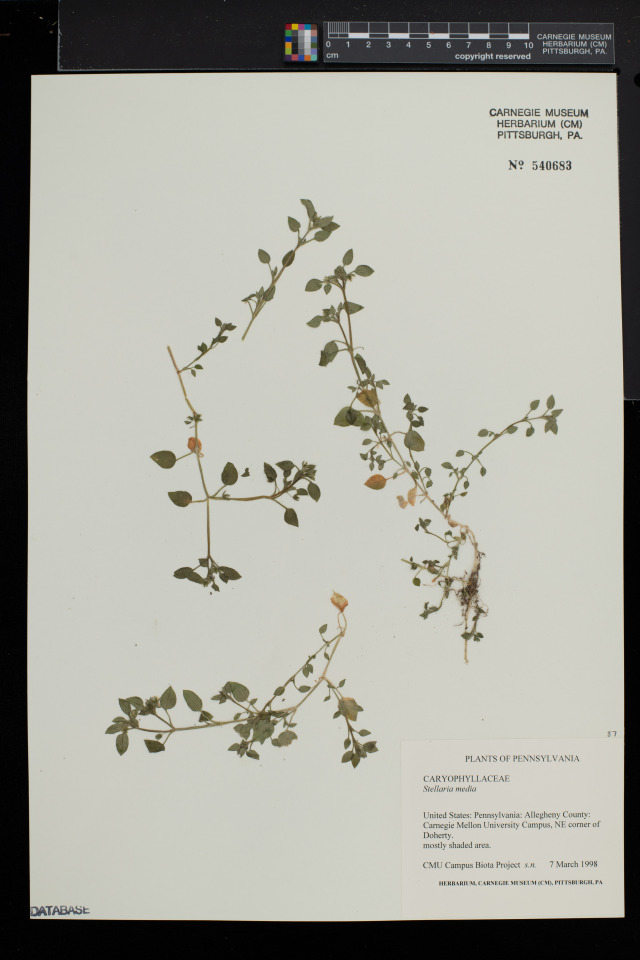

Collected on this Day in 1998: Common Chickweed

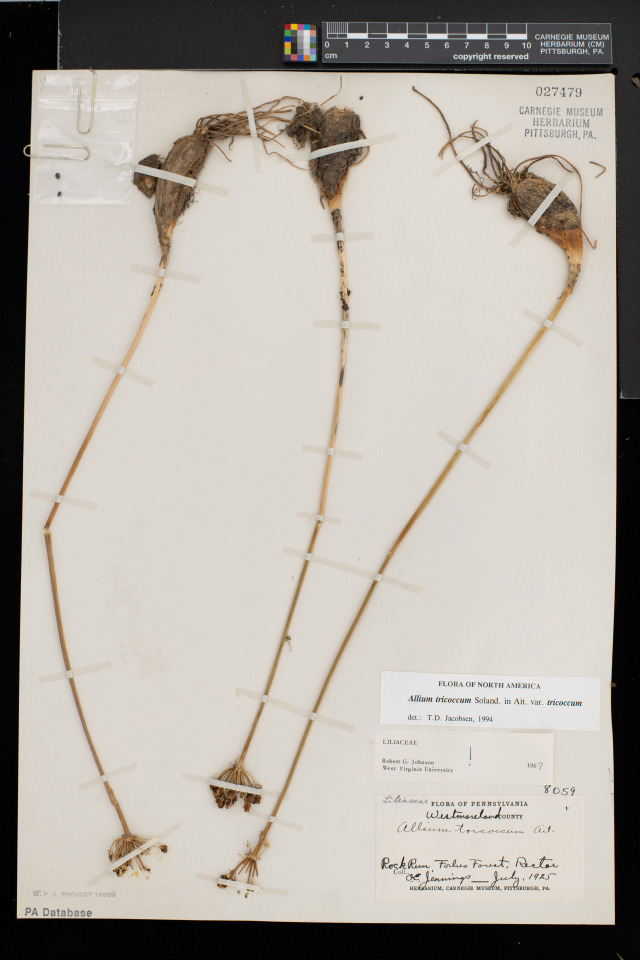

Collected on this Day in 1925: A Flower with No Leaves?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heberling, MasonPublication date: January 11, 2022