Discovering a new species is exciting but determining whether it’s a new species can take some doing.

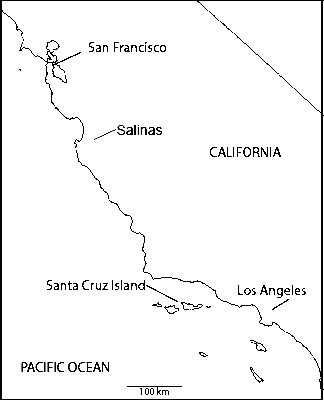

During our project on land snails in the California Borderlands, team member Jeff Nekola discovered a population of the land snail genus Trilobopsis on Santa Cruz Island (Fig. 1). That genus does not occur on any other California Channel Islands; in fact, the closest known mainland locality for that genus is 335 km (210 mi) north in the Salinas Area. We recognize that conditions on the northern Channel Islands tend to be cooler than the adjacent mainland, due to the California Current, and some other typically northern plant and animal taxa (or close relatives) also occur surprisingly far south on the northern islands. The Santa Cruz Island population of Trilobopsis represents a serious range extension to the south for the genus (Fig. 2). Is it merely a range extension of a known species, or could it be a new species?

Peculiarities about the distribution of Trilobopsis on Santa Cruz Island make us wonder if it is a long-established native species or a recent introduction from the mainland. Its localized occurrence on Santa Cruz Island spans only a couple of hectares (a few acres) near an area where humans have been active over the past century or so. Small ranges, near human activity, often hint that a population was introduced. In contrast, if the snail had been on the island for thousands of years, we would expect it to have spread to other parts of the island that have suitable habitat.

Fortunately, team member Barry Roth is an expert on Trilobopsis. He is a very careful worker, scrutinizing shell features and internal soft-part anatomy before drawing conclusions. His impression is that the Santa Cruz snail is different from any described species. The next question could be, to what mainland form is it most closely related?

These days, DNA can supplement evidence from shell and internal anatomy features to help elucidate relationships. To get DNA, we usually need live-caught individuals. While museum collections contain libraries of snail shells, and sometimes soft parts, rarely do they contain all the species needed, or fresh enough DNA for the comparison. So, it was time for a field trip.

In August 2019, team member Charles Drost organized an expedition to northern California to seek live specimens of Trilobopsis species for DNA. Jeff had annotated numerous maps with known locations, compiled from some of my past field work (when I was a student at Berkeley in the mid-1980s) and extensive field work by Barry. Fortunately, despite the normal late summer drought conditions, we were able to find living specimens of Trilobopsis at nearly all the target sites we visited.

We were struck by the differing habitats of some populations. We think of typical Trilobopsis species living in talus rock piles (as does the one on Santa Cruz Island), but we found some populations living in leaf litter, and one population we found was living inside of rotting logs (Figs. 3-4).

One likely side benefit of this research will be a revision of the genus; there might be more species of Trilobopsis than currently recognized, or there might be fewer species than currently recognized if some forms simply look different by growing in different environments.

We await results of the DNA comparisons, so we can learn which mainland populations are most closely related to the Santa Cruz Trilobopsis. Gotta love those California snails.

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.