by Bonnie Isaac

Fall is typically the time of year when we think plants are getting ready for winter. Think of trees changing colors and losing their leaves. Actually, some plants are just beginning to come into their own at this time of year. The New England Aster is at its prime bloom now. The purple, or sometimes pink, ray flowers are a spectacular sight along our open roadsides and fields.

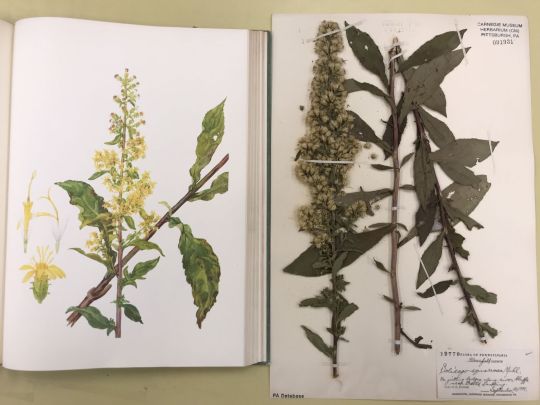

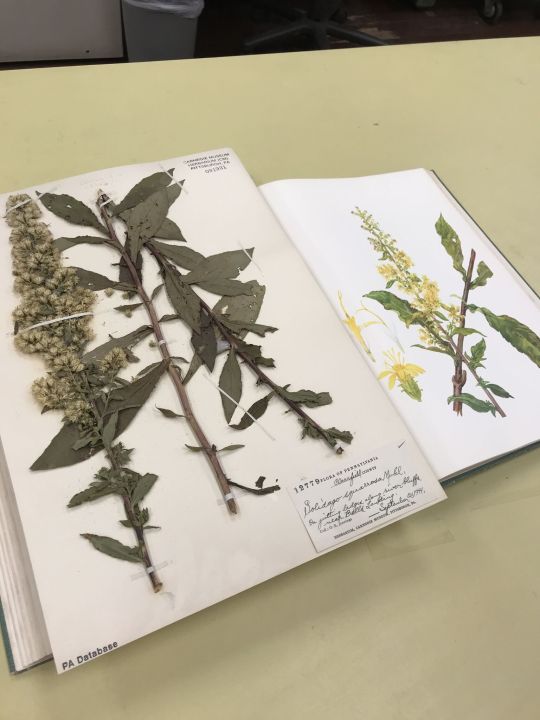

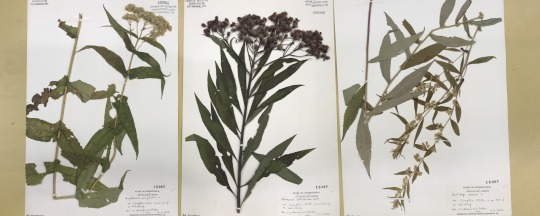

New England Aster is common across Pennsylvania and is known from almost all counties in the commonwealth. This beautiful plant is a member of the Aster family which is commonly called the Composite family. This family is called the composite family because the flower heads are made up of many small flowers (florets) close together composing what looks like one larger flower.

Next time you look at a dandelion, daisy, or sunflower, look closely. You can see many florets. Flowers, like the New England Aster, that bloom late in the year, are very important sources of nectar for bees and butterflies.

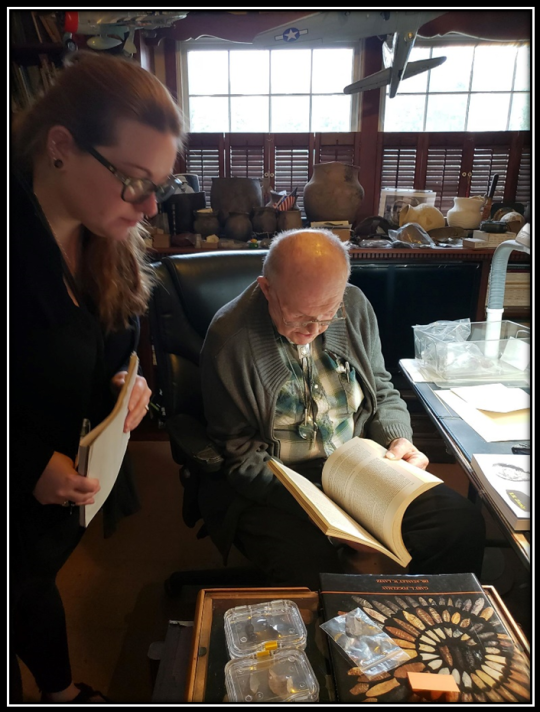

Bonnie Isaac is the Collection Manager in the Section of Botany. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.