by Sarah C. Williams

Here in the section of Botany we’ve adapted in some strange ways, just like plants do, to the changes of the past year and a half. Let’s learn about the off days of some of our Super Scientists in the Section of Botany!

Mason Heberling, Assistant Curator of Botany

Collecting specimens has become a focus as more time was able to be spent in the field when we weren’t allowed to be at the museum. As our new Botany Hall entrance video shows, Assistant Curator of Botany, Mason Heberling and Collections Manager Bonnie Isaac collect plant specimens on a pretty regular basis. They also snag iNaturalist observations for these plants, taking photos that show what the plant and habitat looked before being picked and pressed.

Mason studies forest understory plants, in particular, introduced species and wildflowers in our changing environment. Mason has a bunch of fun projects going on this summer, ranging from coordinating seed collections of an uncommon native grass to send to Germany for a large greenhouse study to working with a team of students to study the effects of climate change and introduced shrubs on our forest wildflowers.

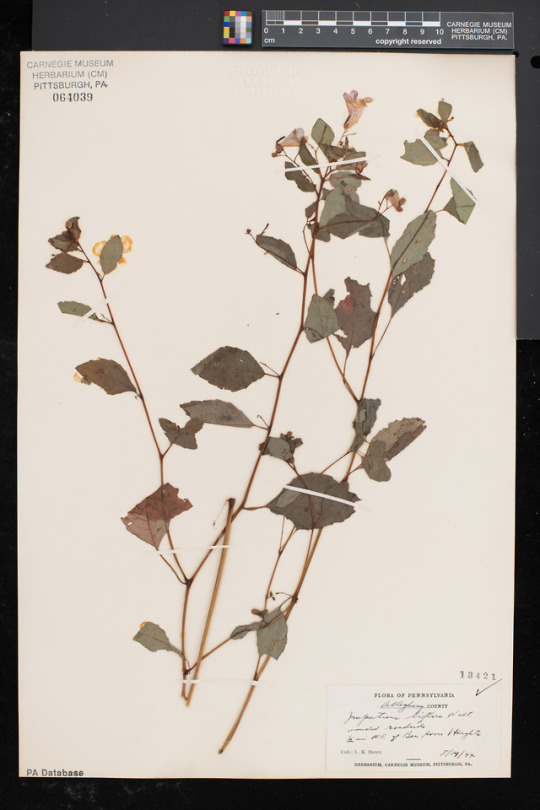

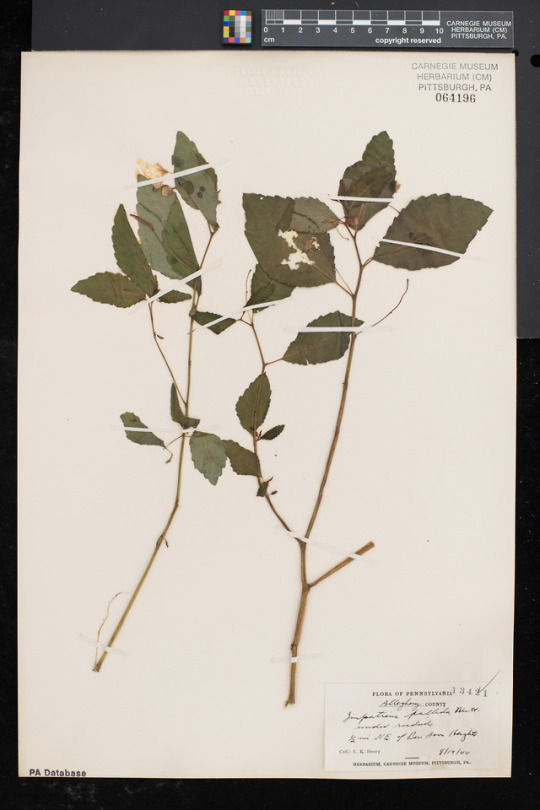

In addition to work in the field, the herbarium has been a busy place this summer too! Mason has been working with Alyssa McCormick, an undergraduate research intern from Chatham University, to examine stomata (the pores on leaves for air exchange for plants to “breathe”) and leaf nutrients in everyone’s favorite plant – poison ivy! Poison ivy has been previously shown to grow bigger and cause nastier skin rashes with increasing carbon dioxide in our air due to fossil fuel emissions. Alyssa is using specimens collected as long ago as the 1800s to examine long term changes in poison ivy.

Mason, where can we find you on a Saturday?

“This summer has been a lot of going to various places around western PA like Presque Isle or Idlewild to get out and enjoy the fresh air with my family. I can also be found most Saturdays around the house doing chores!”

Bonnie Isaac, Collection Manager

Bonnie, one of CMNH’s TikTok celebrities, and All-Star in the Mid-Atlantic plant world, has spent a lot of the past year doing fieldwork. Her PA Wild Resource Grant involved looking at most of the populations for 10 Pennsylvania rare species. She and husband Joe Isaac spent many days on the road and a few in the bog! You can see some of her videos about these unique Pennsylvania finds on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Tiktok account: @carnegiemnh.

She diligently keeps track of various data points from latitude and longitude and elevation, to flower color, size, and associated species within a habitat. In addition to trying to make sure the plant names in our database are correct, she has also been busy georeferencing some of our specimens so that we can see on a map where each one was collected.

Bonnie, where can we find you on a Saturday?

“On most Saturdays I am either home taking care of my many chickens or getting some exercise in one of my kayaks with my spousal unit, Joe. I sometime even take a fishing pole for a ride or see how many different kinds of plants I can find on a hike. As long as I can get outside with Joe, I’m happy.”

Cynthia Pagesh, Herbarium Assistant

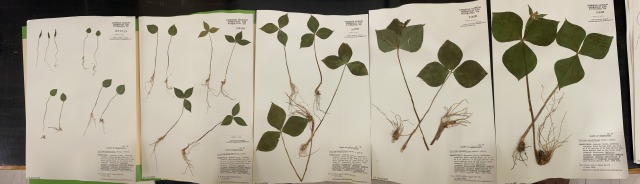

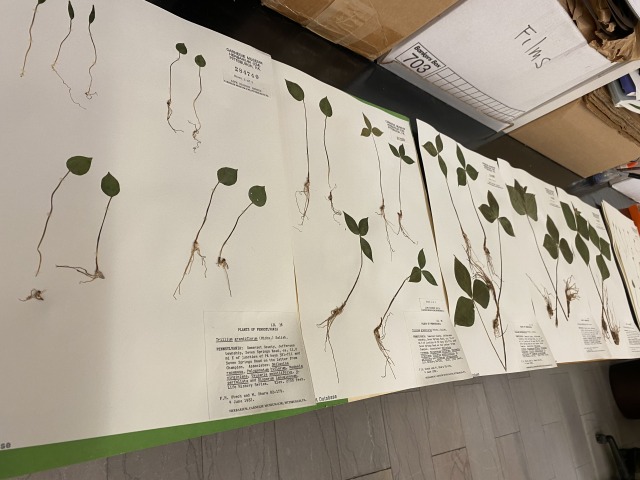

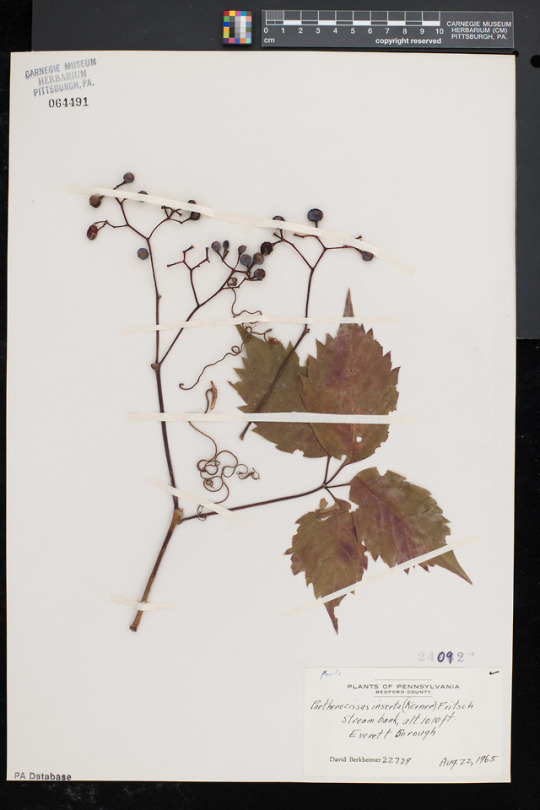

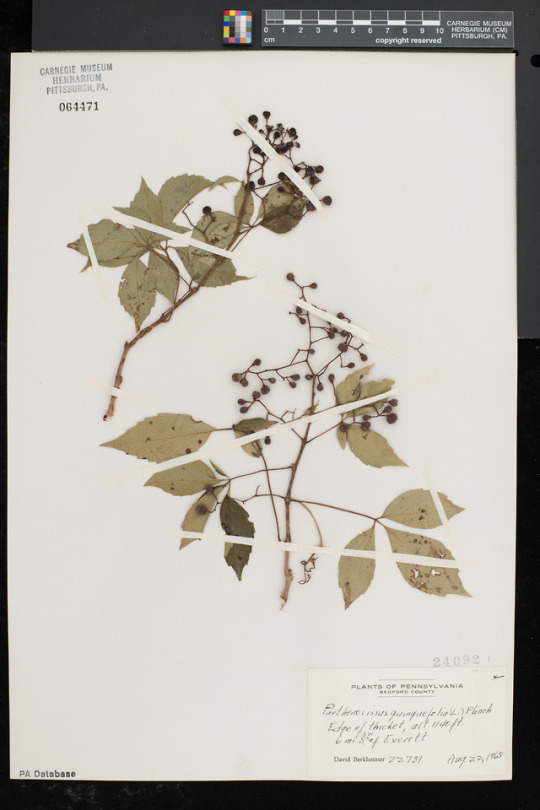

Specimens make their way home to the museum, where we assure they’re bone dry, flat as a pancake, and have been frozen twice to get rid of any pests. They then find their way into the nimble hands of Cynthia Pagesh, our resident plant mounter. Cynthia has luckily been able to do some mounting both onsite and at home over this past year, really honing her craft. She uses Elmer’s glue, dental and sculpture tools, linen tape, and a paintbrush akin to a magic wand: transforming roots, stems, flowers, and fruits into scientific and artistic renderings on an 11.5×16.5” archival herbarium sheet.

Mounting can be very detailed and challenging: wrangling a dry and brittle rare plant you want to salvage every detail from, or an oversized leaf ‘how-will-this-all-fit?’ ordeal, or finessing a delicate petal that glue is especially heavy on. Bulky bits, crumbly bits, spiky no nos: Cyn handles them all. Her work is just as much an art as it is a science. When she’s not making masterpieces, she’s probably doing something with plants.

Cyn, where can we find you on a Saturday?

“You can find me on Saturdays helping prune young trees in my community, collecting wildflower seeds or in my kitchen making preserves or homemade pasta noodles. I volunteer in vegetable, herb and flower gardens. I have a pollinator garden at home and raise Monarch caterpillars. I tag and release them to migrate south.

There are lots of Community Science projects for people of all ages: ask someone to help you find one related to a subject you have an interest in. I have an interest in pollinators including bees. I participate in a Community Science Project every Summer that counts types of bees on certain plants when they bloom.”

Iliana DiNicola

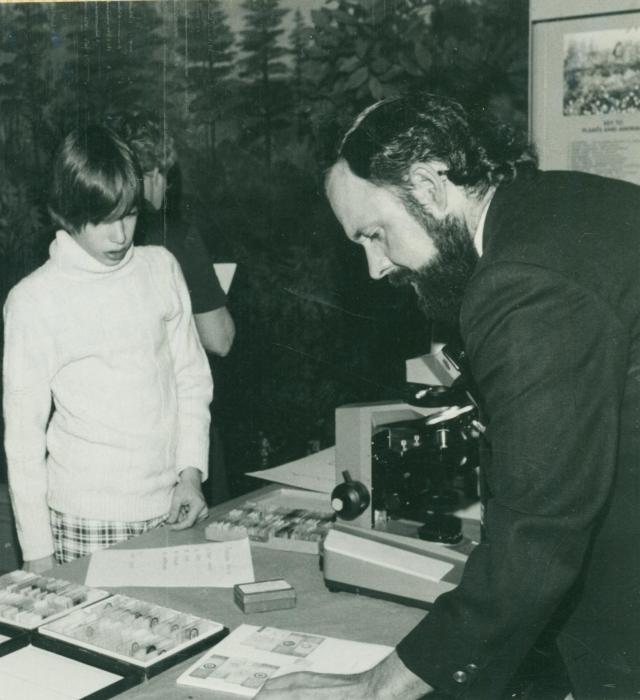

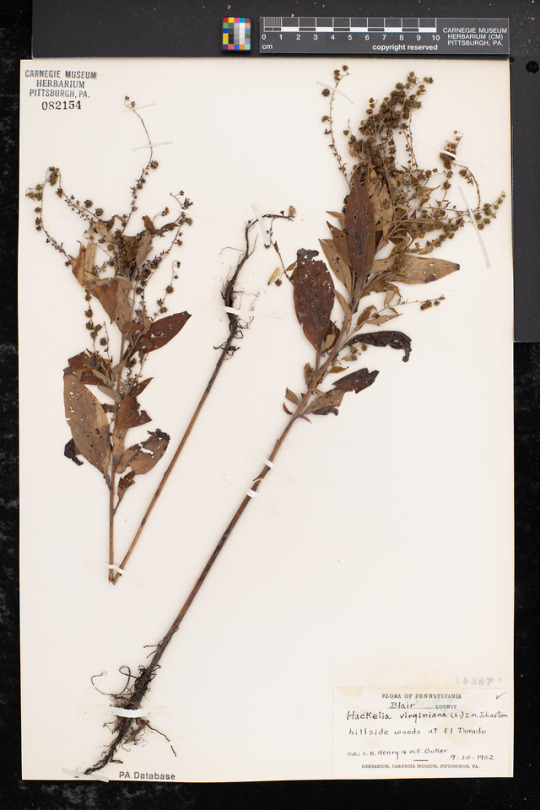

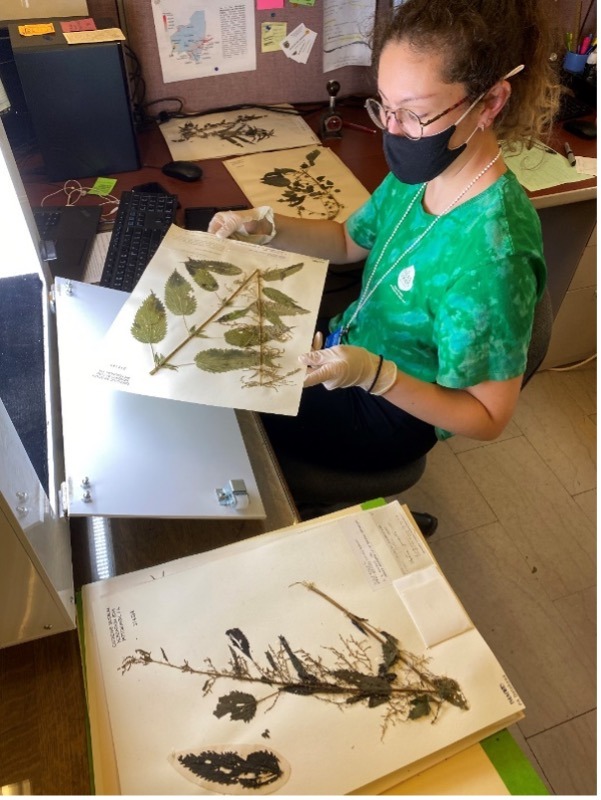

After another stint in the freezer for bugs-be-gone, it’s everyone’s favorite day: Picture Day! Each plant: sturdy and mounted, all data logged and super official, makes their way to the imaging station to spend some time under the bright lights. Since 2018, students, interns, and volunteers have lovingly held these plants’ hands as they get their close ups. We take high definition photos using a specially made lightbox and special software.

While this is part of a limited project, called the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis, we are still hard at work going into our last year of the time we were given. This past schoolyear and summer, former Pitt student, Iliana DiNicola was taking pictures for us on the regular while also interning with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy. She just graduated and I’m excited to hear what she does on her Saturdays in the future.

Iliana, where can we find you on a Saturday?

“I just graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a degree in Environmental Studies, and I am now on the lookout for any jobs related to the environment back in my hometown of Phoenix, Arizona. I am interested in working with anything from sustainability, to policy or political work, or maybe even something more related to ecology and outdoor work.

On a Saturday, I am definitely helping clean my house since I am a semi-clean freak, I love to go hiking if the weather isn’t too hot, enjoy drawing and working on any art projects, or work on my future hydroponics garden.

As somebody who interned for Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, I highly recommend participating in any camps or activities the conservancy has to offer. It was super fun learning more about Pittsburgh’s history and ecology and getting to teach kids about these topics, alongside participating in fun outdoor activities.”

Sarah Williams, Curatorial Assistant

Next up, Sarah Williams, the Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Botany, is overseeing the digitization project, morphing the photos from raw camera files into smaller files for sharing and detailed files for archival storing using Adobe Lightroom. She takes the images from the newly photographed specimens and makes sure they get uploaded onto the Mid-Atlantic Herbaria Consortium’s website to be shared far and wide across the world.

There is also a lot she does in sorting, filing, and taking care of the specimens as well. She does a bunch of scheduling, hiring, and training of work study students, interns, and volunteers. We consider her a jack of all trades.

Sarah, where can we find you on a Saturday?

“Most weekends I work with a local catering company called Black Radish Kitchen. I usually end up serving delicious vegetable and farm focused meals at least one day a week, commonly Saturdays because they’re prime for celebrations. The re-start up since the pandemic has been cautious, and I’m excited to be amongst people and help them to make mouthwatering memories again. I’ve worked in the restaurant industry for over a decade and the skills I’ve learned doing it as well as the friends I’ve made are matchless. It has a big piece of my heart.

I also moved into a new house this year about five minutes from my mom, so if I’m not running to say hi to her and ‘borrow’ some groceries, I’m doing laundry, dusting and yardwork… but only after I sleep in, eat some delicious breakfast with my partner, and hang out with our two cats, Santi and Gil.”

We hope you enjoyed getting to know us here in the Section of Botany, look forward to updates and more introductions in the future as we continue to host volunteers, federal work-study students, and interns on their journeys to learn even more about the plant kingdom.

Sarah Williams is Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

How Do You Preserve a Giant Pumpkin?

Fall Blooms Rival Those of Spring

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Williams, Sarah C.Publication date: September 24, 2021