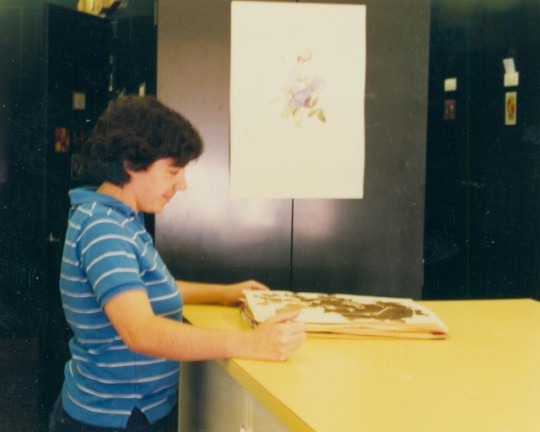

On August 7, 1989, Bonnie Isaac started at the Carnegie Museum. She was initially hired at the museum to work on a project to database the plant collection, making it searchable and therefore more useable to understand the occurrence and distribution of plants across Pennsylvania (and beyond). Since then, a lot has happened. Thirty years later, Bonnie is now Collection Manager in the Section of Botany and Co-chair of Collections.

It is no exaggeration to say Bonnie’s influence on the Section of Botany has been monumental. And continues to be.

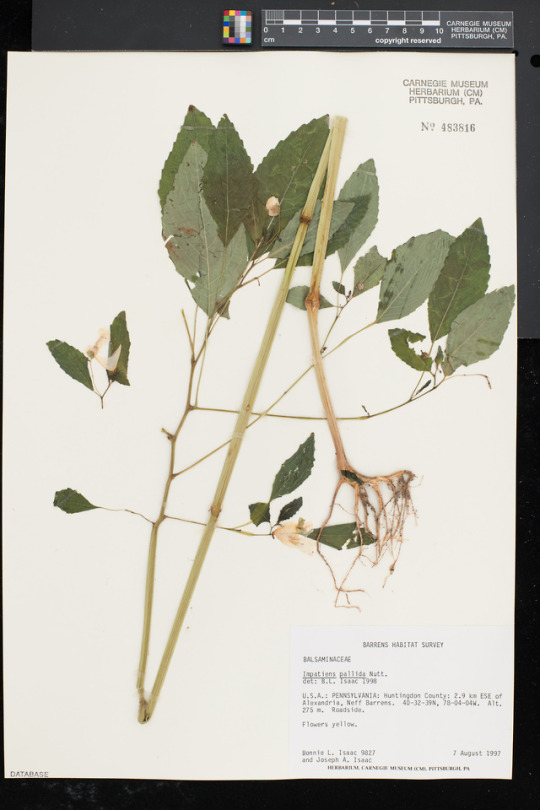

As one of the top plant collectors over the Carnegie Museum’s 120+ year history, she has actively contributed to the growth of the herbarium, collecting several tens of thousands of specimens from across Pennsylvania and North America. These specimens now reside in herbaria across the world and are actively used by researchers around the world to make exciting discoveries.

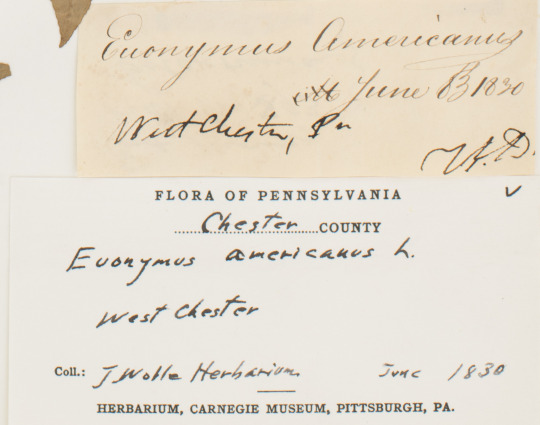

Bonnie played a pivotal role in the digitization of the Carnegie Museum herbarium, one of the first of its size to have all specimens in the entire collection with label data entered into a database and publicly available online. A huge accomplishment that took over a decade of her career to complete, the collection database has increased the research value and led to a massive increase in specimen use. The digitization of the herbarium continues today through a project facilitated by Bonnie and funded by the National Science Foundation to make high resolution digital images and georeferences (assign latitude/longitude to plot on a map) to all specimens collected in the region.

Although she’s humble about it, Bonnie is an incredible field botanist and leading expert on the plants of Pennsylvania, especially those rare and threatened species of conservation concern. An expert in natural history collections management and methods, Bonnie has a specialized diploma on herbarium techniques from Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, England. She has a master’s degree from Youngstown State University, where she studied the ecology and distribution of a rare species.

Bonnie’s science and botanical knowledge impacts conservation decisions. Since 2001, she has served as a member of the Vascular Plant Technical Committee of the Pennsylvania Biological Survey, serving at various times over the past decades as president and recording secretary, which advised the state in determining the status of endangered and threatened plant species. She is currently working on a project funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources through the Wild Resources Conservation Program, revisiting many historic sites of 10 threatened species across the state to assess their current rarity status.

Beyond the walls of the museum, Bonnie has a huge impact on botanical research in Pennsylvania and fosters a public appreciation for the role of plants in our lives and ecosystem health. She is a founding member of the “Pennsylvania Botany Symposium,” a group of committed volunteers who provide education and networking opportunities for professionals, amateurs, and students of botany, including a biennial symposium that gathers Pennsylvania botanists of all levels. Bonnie is also very active in the Botanical Society of Western Pennsylvania, one of the oldest botanical organizations in the country. She has served as President of the organization since 2005.

And if that is not enough – she is friendly, too!

Happy work-iversary, Bonnie!

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.