by Sara Klingensmith

Fungi, a vast group neither animal nor plant, comprise a diversity of organisms ranging from microscopic, unicellular yeasts and molds to enormous, hardened brackets, to jiggly, gelatinous structures, to classic cap and stem mushrooms, to “what on Earth is THAT?” The enormity of variation in shapes, sizes, and colors is astounding. While some fungal forms may resemble plants in appearance, all fungi lack structures associated with photosynthesis—they are more closely related to animals than they are to plants. Fungi even share a compound called chitin, which is found in their cell walls, with arthropods. Some taxonomists place them in a grouping called Opisthokont, a position closer to animals in a complex tree of relationships. Fungi are ubiquitous, found in a variety of ecosystems and even inside living organisms—what are they doing?

Decomposition and Nutrient Recycling

Saprotrophic fungi are the clean-up crew! Unlike plants that harness energy from sunlight, fungi extend hyphae, or filamentous tube-like structures into their source of nourishment. Collectively, hyphae are referred to as mycelium (mushroom “roots”), which form the main, life-sustaining part of the fungus. These hyphae secrete enzymes that help break down the rotting wood, leaves, and other organic debris, liberating nutrients that are not readily accessible to other life forms. These hard-to-reach nutrients are often locked up in lignin and cellulose—tough compounds that comprise wood and plant cell walls. Often, a single rotting log will support a variety of saprotrophic fungi participating in successional stages of decomposition. This continued release of nutrients helps sustain many generations of organisms within an ecosystem and prevents the establishment of ever-expanding debris piles.

Pathogens & Parasites

These particular ecological niches often receive a bad reputation because of associations with reduced crop yields, the death of favorite landscaping plants, and even cases of athlete’s foot and ringworm. In the broader scope, native pathogens and parasites are a fundamental component of the complex balance of life and death. They help prevent organisms from exceeding carrying capacity, a service essential to successional ecosystem processes and the establishment of stable populations. Some fungal tree pathogens are even responsible for shaping habitats by creating hollow cavities and tree falls.

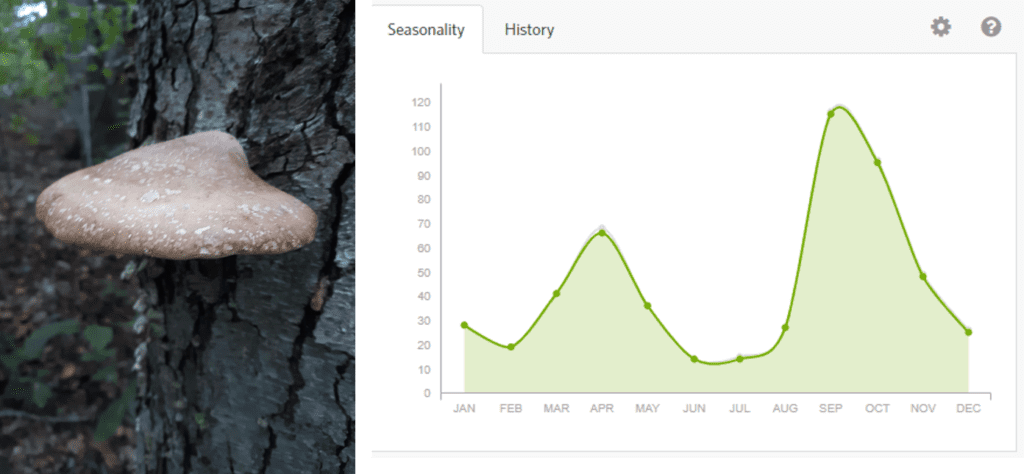

Fungal pathogens in plants are frequently host-specific and some are restricted to infecting certain areas of the host. For example, mossy maple polypore (Rigidporus populinus), which causes white rot in living tree tissues, is usually found on maples and oaks, whereas mayapple rust (Puccinia podophylli) only infects mayapples. Some fungi parasitize a wide range of insect species and even other fungi. Some of these species are currently being studied and implemented as biological controls against insect and fungal agricultural pests and detrimental forest pathogens.

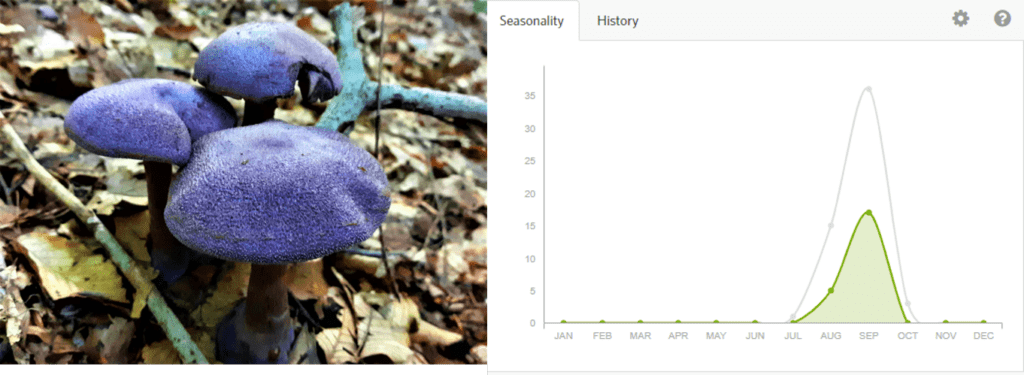

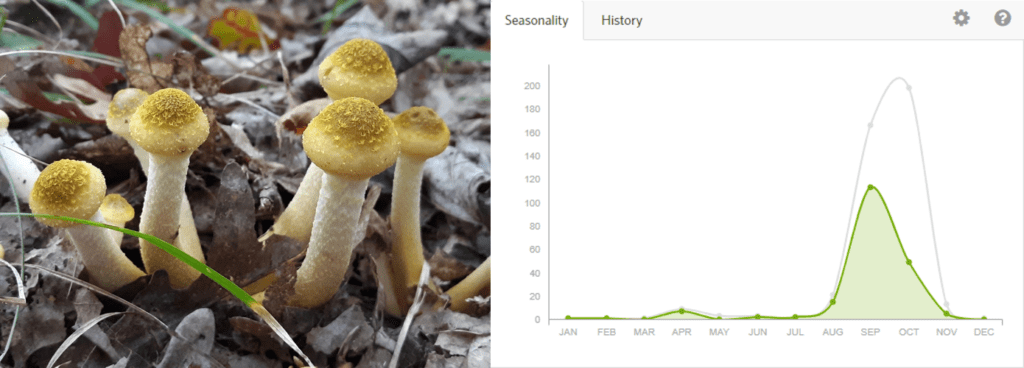

Cordyceps sp. provide some of the more charismatic encounters with parasitic fungi-insect relationships here in Pennsylvania. Scarlet caterpillar club (Cordyceps militaris) only targets pupating butterflies and moths. After it infects the host, the mycelium empties the host of nutrients and then forms the species’ distinctive fruit. A common forest mushroom, oak-loving gymnopus (Gymnopus dyrophillus) can be found with tumor-like growths caused by fungal parasite Collybia clouds (Syzygospora mycetophila).

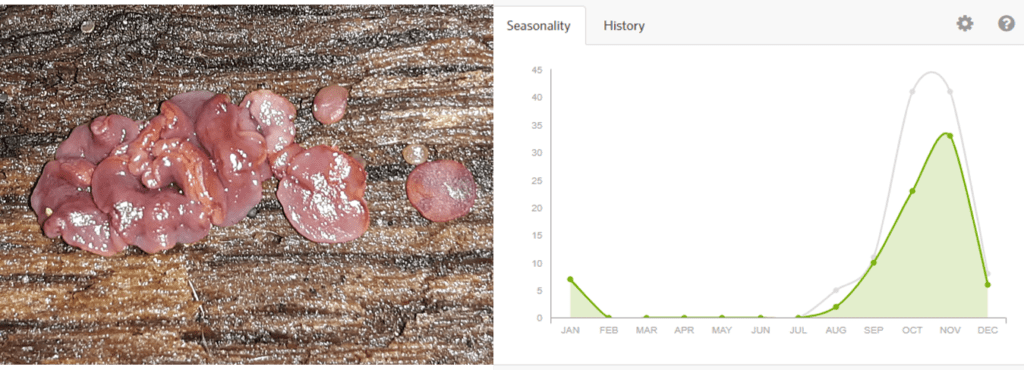

In some cases, it is not clear who is parasitizing who. For example, aborted entoloma (Entoloma arbortivum) was once thought to be another victim of honey mushroom (Amellaria sp.) parasitism. Amellaria sp. can parasitize a variety of trees and shrubs, spreading through large areas of forest like one titan organism. However, a 2001 study of the “aborted” fruitbodies, or carpophoroids, suggests that the entoloma is parasitizing the honey mushroom, and thus may be considered as a potential biological control for Amellaria sp.

Symbiotic Relationships & Carbon Sinks

“When algae met fungus, they took a ‘lichen’ to each other.” That’s how the story goes. Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a partnership between a fungus and an algae or cyanobacteria. The fungi provide protection, and the photobiont (algae or cyanobacteria) provides the sugars obtained from photosynthesis. Certain species of lichen can be regarded as air quality bio-monitors because of their sensitivity to air pollution.

Roughly 80-90% of plants need mycorrhizal fungi partners to survive. Some mycorrhizal fungi may form sheathes around plant roots (ectomychorrhizal fungi) or live in the plant roots (endomychorrhizal or arbuscular fungi), and some form special relationships with particular plant groups. In exchange for plant-produced carbon, in the form of sugars known as photosynthates, these symbionts break down and gather up minerals and nutrients that would otherwise be locked up in the soil. Furthermore, mycorrhizal fungi are capable of transferring carbon from one tree to another. They can even help plants communicate, provide “parental care” to saplings, or sabotage competitors. Scientists refer to this phenomenon as the “Wood Wide Web.” Additionally, these vast, dense fungal networks help store carbon in the soil in the forms of mycelial necromass and ever-expanding active mycelium. Both forms stitch the soil together, making it more resistant to erosion.

Food Web Links

Fungi serve as food for many species of wildlife. Insects and other arthropods rely on many species of fungi for food. Pleasing fungus beetles are aptly named for their reliance on fungi as a prominent food source. Some fungi feeders may even retain toxins from their meals of poisonous fungi species to help with their own protection from predators.

Many of our favorite foods and life-saving medicine would not be possible without fungi. When we bake bread, we need yeast to make the dough rise. Many fermented foods require a fungal agent, and to combat bacterial infections, we rely on penicillin derived from Penicilium notatum – a species of mold.

To turn the tables, certain fungi species are predatory! Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus sp.) are considered saprotrophs with a sinister side. They have toxic, sticky mycelium that traps and paralyzes nematodes. Once the nematode is trapped, hyphae penetrate and dissolve the organism. This predatory strategy helps the mushroom acquire nitrogen in nutrient poor substrates.

Fungi are far too complex for every relationship to be even mentioned here. Although fungi have long been overlooked in terms of conservation, they are gaining attention. The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) is working on mapping mycorrhizal networks in an effort to support underground biodiversity and draw attention to the role these fungi play in supporting healthy ecosystems and mitigating climate change. At Powdermill Nature Reserve, an iNaturalist project collects fungi, lichen, and slime photo observations from community participants to help document biodiversity: Fungi of Powdermill Nature Reserve · iNaturalist. From fine dining to influencing entire ecosystems, fungi are essential to life.

Sara Klingensmith is an Environmental Educator and Naturalist at Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center.

Sources

Arora, D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: a comprehensive guide to the fleshy fungi. Berkeley (California): Ten Speed Press.

Binion, D. (2008). Macrofungi associated with oaks of Eastern North America. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Czederpiltz, D. L. L., Volk, T. J., & Burdsall, H. H. (2001). Field observations and inoculation experiments to determine the nature of the carpophoroids associated with Entoloma abortivum and Armillaria. Mycologia, 93(5), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2001.12063219

Lee CH, Chang HW, Yang CT, Wali N, Shie JJ, Hsueh YP. Sensory cilia as the Achilles heel of nematodes when attacked by carnivorous mushrooms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Mar 17;117(11):6014-6022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918473117. Epub 2020 Mar 2. PMID: 32123065; PMCID: PMC7084146.

Society for the Protection of Underground Networks, SPUN

Tree of Life Web Project, Eukaryotes (tolweb.org)

Related Content

Fungi Make Minerals and Clean Polluted Water Along the Way

A Lot To Be Fascinated By In the Herbarium

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Klingensmith, SaraPublication date: June 10, 2022