Murray Crayfish

The Murray Crayfish (Euastacus armatus) is a favorite of Jim Fetzner, Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Zoology. It can be found in the Murray and Murrumbidgee River catchments in the Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria. The species was originally described back in 1866 by Eduard von Martens. The species is becoming rare due to habitat degradation and overfishing and is considered Threatened or Endangered by Australian conservation agencies. The species is one of the largest species of freshwater crayfish in the world, second only to the Giant Tasmainan Freshwater Crayfish, Astacopsis gouldi. It can reach maximum sizes of over 4 pounds and about 16 inches in length. The claws are typically bright white, and the body is usually black or dark greenish/brown and covered in large spines, making it a quite striking crayfish when seen in the wild.

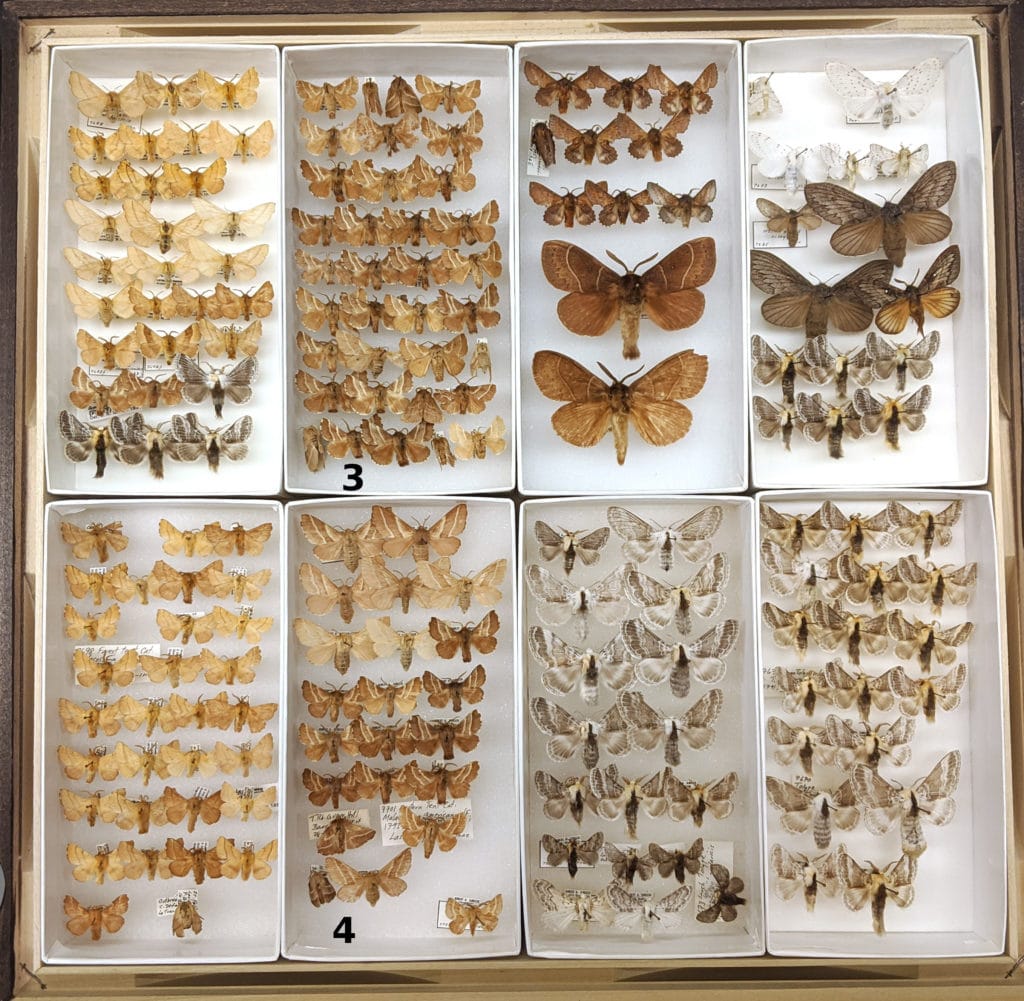

Lasiocampidae moths

Lasiocampide is the favorite moth family of Vanessa Verdecia, Scientific Preparator in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology. There are approximately 2,000 species worldwide which include moths commonly referred to as the eggars, lappet, and tent caterpillar moths. Check out this drawer which includes mixed species that need to be curated into the main collection. These moths have reduced mouthparts and do not feed as adults, so all the eating is done in the caterpillar stage. Some species in this family are well known, including the Eastern Tent Caterpillar (tray 3 and 4), which is a pest. However, there is interesting species diversity in the Tropics, with species waiting to be discovered and named. Although there are only 35 species in the US, questions remain about the life cycles and number of species in some of the groups. Field work and molecular data using specimens in the Carnegie collection will help to answer these questions and revise studies that have been published in the past.

Bold Jumpers

Phidippus audax, commonly known as the Bold Jumper, is one of the favorite species of invertebrates of Catherine Giles, Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology. They’re very common in North America, but what makes them stand out from others is their iridescent chelicerae—their “jaws.” Members of the genus Phidippus can all easily be identified by this iridescence, and typically males will have brighter iridescence to attract a mate. P. audax is very docile with some people even keeping them as pets! Spiders are always handy to have around as they eat problematic insects, like mosquitoes. Specimens of P. audax in our spider collection have been found in nearby Frick Park. See if you can spot these shiny-faced little ones on your next walk through the park!

Manticora, Adult Beetle

Manticora imperator is a tiger beetle in the family Carabidae, and a favorite of Bob Davidson, Collection Manager Emeritus in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology. The genus Manticora (“the one who devours men”) consists of 15 known species confined to the southern portions of Africa, mostly to the oldest geologic portions of that region, and mostly to open desert and dry savannah habitats. They are relatively primitive, flightless, predatory black tiger beetles of enormous size. The males of some species are particularly spectacular, with huge asymmetrical mandibles, reaching the extreme in Manticora imperator, with a toothed left mandible and a larger right mandible bent like a sickle. Mandibles in both sexes are used to attack prey, and, in males, also to combat other males and to clasp the female during copulation.

Manticora, Beetle Larva

The larva of Manticora mygaloides, one of 15 known species in this genus which is only known from the southern portions of Africa. The Manticora larvae look and behave more like tiger beetle larvae from other parts of the world, except that they are enormous. They mostly occur in open desert and dry savannah habitats, where they dig a vertical burrow up to a meter in depth, depending on substrate, which they can drop down into when disturbed. The larval head is like a big armored plug with jaws attached. In attack mode, they block the burrow entrance with the head (making the hole difficult to see) and wait. There is also a large hook toward the rear on the larva’s back which makes it difficult for anything to dislodge it from the burrow. If something edible gets within striking distance, the larva throws its forebody out, grabs with its large jaws, and drags the prey into the burrow.

Death’s Head Hawkmoths

The African Death’s Head Hawmoths, Acherontia atropos, are found in Europe and Africa. They are members of the family Sphingidae, which include about 1,450 species commonly referred to as the hawkmoths, sphinx moths, and hornworms. There are two other species in this genus—A. lachesis and A. styx, which are found in Asia. All three species are known for the skull-like color pattern formed by the scales on the thorax and the rib-like color patterns on the abdomen, which have inspired stories and superstitions in the regions of the world where they occur. Acherontia styx was referenced in the book The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris. A scene of the movie adaptation was filmed in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology which depicted an entomologist identifying the pupa of a sphingid moth. The drawer imaged here includes specimens in the caterpillar and pupal stages of Acherontia atropos, prepared and preserved dry according to historical standards. Larval and pupal specimens are now preserved in ethanol. All three species are known for their interesting biological adaptions including a mechanism that allows them to squeak, and the ability to feed on honey which they steal from the combs of honeybees.

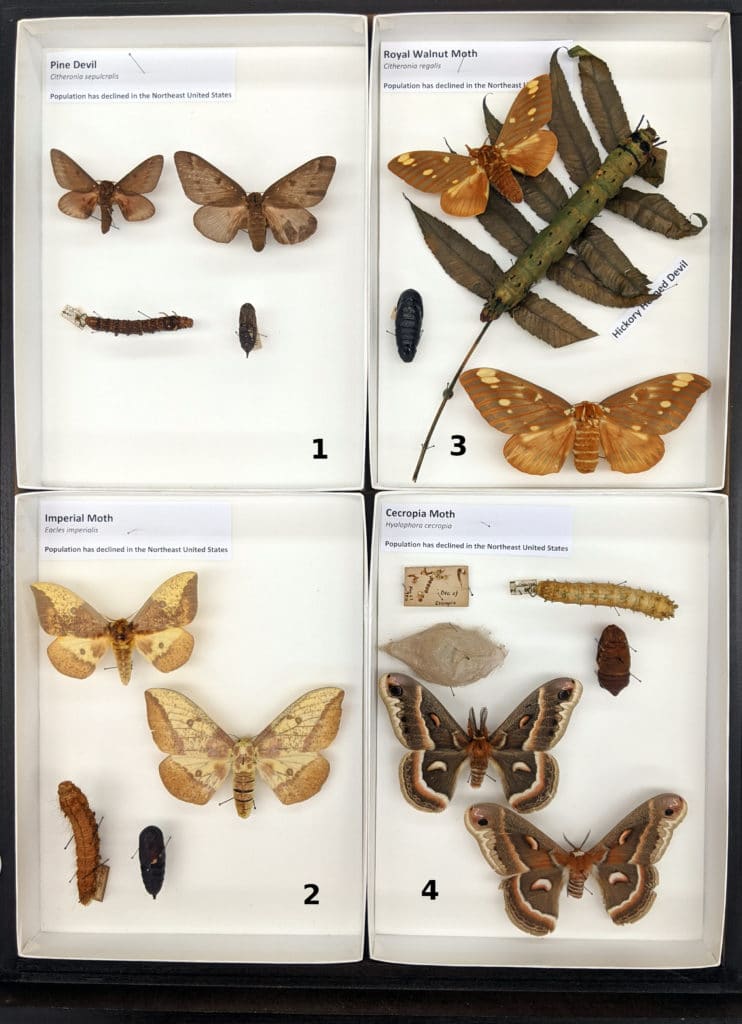

Saturniidae moths

The family Saturniidae, which includes about 2,300 known species, are commonly referred to as the royal, emperor, and giant silk moths. They are known for their large size, colorful scale patterns, and some have “eyespots” on the hindwings that serve as a defense mechanism for scaring off predators. The adults have reduced mouth parts, so they do all their feeding in the caterpillar stage and cannot feed as adults. Therefore, they only live for a few days in the adult stage—long enough to mate. Pictured here are some of the species known to occur in Pennsylvania. The Pine Devil Moth (tray 1) and the Royal Walnut Moth (tray 3) are closely related and there is evidence of population decline, especially in the Northeastern United States. They have horns that look scary but are harmless. The Imperial Moth (tray 2) has also experienced population decline and has four color forms seen in the caterpillars. One culture may include dark brown, light brown, red, and green caterpillars all from a single parent! The Cecropia Moth (tray 4) is very common in Pennsylvania but has also experienced population decline that is thought to be due to parasitism by a tachinid fly introduced to control Gypsy Moths, which are an introduced pest that threatens our forests.

Pachyrhynchus specimens

Members of the genus Pachyrhynchus are the favorites of Ainsley Seago, Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology (who calls them “disco weevils”). The glittering colors of these party beetles come from tiny photonic crystals inside their flattened scales; several of Bob Androw’s cerambycids have independently evolved a similar structural color mechanism. No one is sure what these Indonesian weevils use their colors for, but it may be a signal warning predators not to bother… their fused elytra and tough exoskeleton are too thick to pierce.

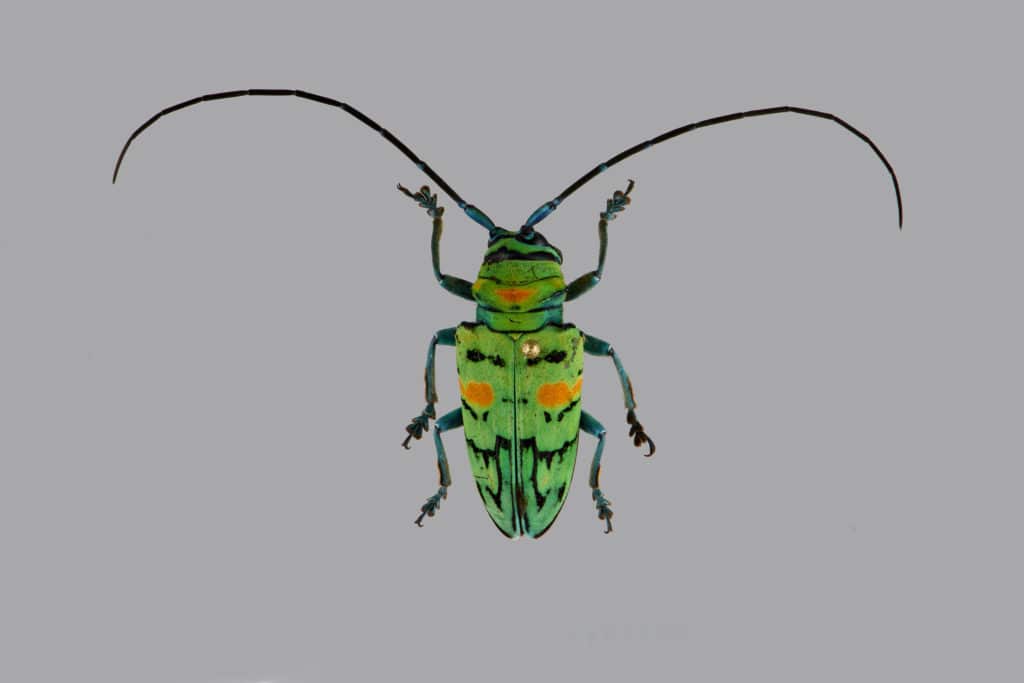

Sternotomus callais

The longhorn beetle genus Sternotomis has convergently evolved structural colors based on three-dimensional photonic crystals, just like those of Pachyrrhynchus but arising from a different ancestral lineage. These colors are created by the nanoscale interactions of photons with a crystalline structure within the beetle’s flattened hairs (“setae”), and will last as long as the specimen itself. Paleontologists have even found fossil beetles that retain their iridescence after 60 million years!

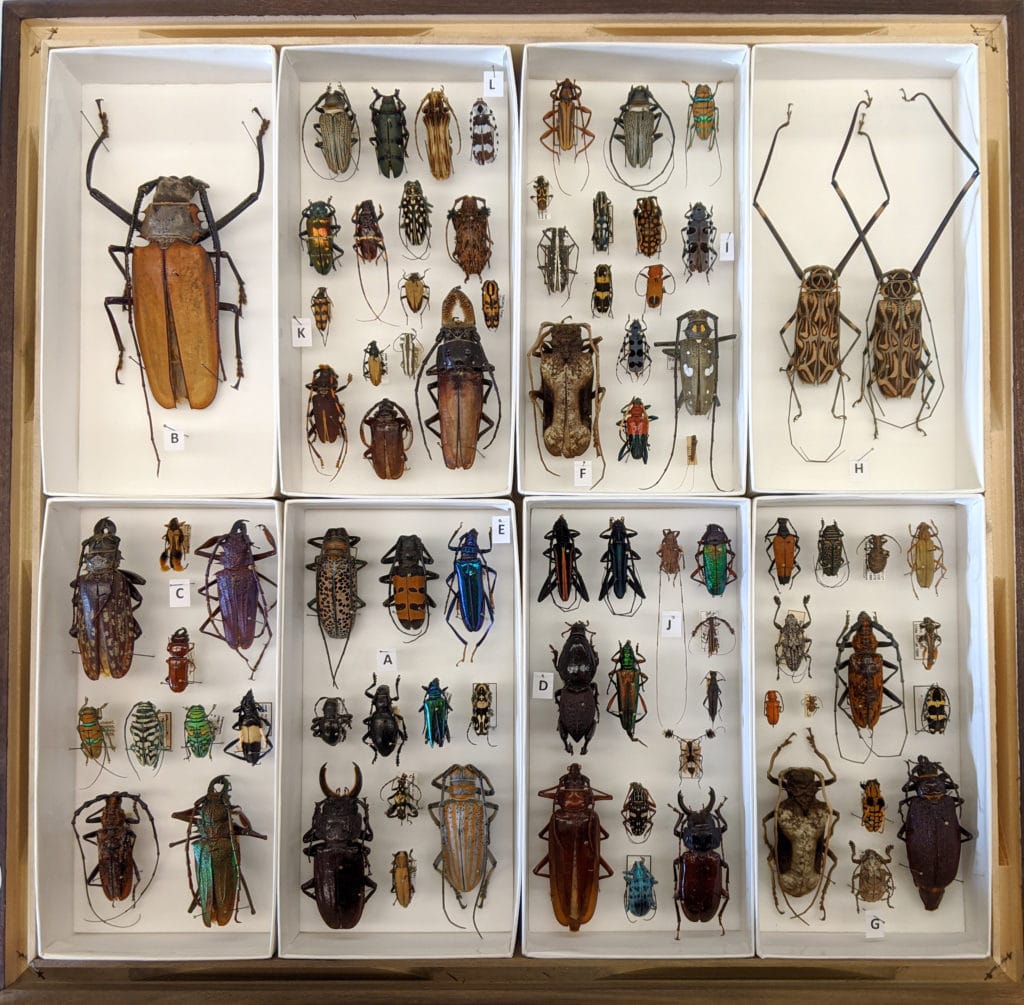

Longhorn Beetles

The longhorn beetles (Cerambycidae) are a favorite of Bob Androw, Collection Manager in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology. Although these beetles are typically known for their very long antennae, that character varies and quite a few species have short antennae.

Check out this drawer of diverse looking specimens from the Carnegie collection which represents just a few of the 26,000 species known. It’s a large taxonomically diverse and economically important family of beetles which contains many common and showy species, some serious plant pests, and a number of species that are considered rare enough to be afforded legal protection.

Some species mimic other insects, such as ants, bees, and wasps in both shape and coloration. The larvae are mostly wood-boring and occur in dead or decaying wood, with a few species feeding on live plant tissue. A few are soil-dwelling as larvae, feeding on the roots of grasses and other plants. The adult beetles have a wide range of feeding habits that include visiting flowers for nectar and pollen; feeding on fruits and sap from trees; and feeding on bark, stems, and leaves. There are also some that don’t feed at all as adults and just one genus, Elytroleptus, is known to be carnivorous as a predator on net-winged beetles (family Lycidae).

A: Moneilema sp. – Subfamily Lamiinae. These flightless species breed as larvae in the living tissue of cactus in the Southwest United States and Mexico. The adults are mimetic of darkling beetles like Eleodes spp., in the beetle family Tenebrionidae.

B: Enoplocerus armillatus – Subfamily Prioninae. This is one of the largest species of Cerambycidae in the New World, surpassed only by the enormous Titanus giganteus. Both occur throughout the Amazon Basin, while Enoplocerus ranges north as far as Costa Rica.

C: Callisphyris sp. – Subfamily Cerambycinae. A spectacular example of mimicry of a wasp by a cerambycid, involving coloration and the fuzzy hindlegs.

D: Hypocephalus armatus – Subfamily Anoplodermatinae. One of the most atypical species of cerambycids, possessing very short antennae, legs adapted for digging and an oddly shaped body. It is primarily soil-dwelling, occurring in the northern parts of South America.

E: Aphrodisium cantori – Subfamily Cerambycinae. While such brilliant metallic colors make this species stand out against a white background, it would well camouflaged in its natural habitat, sitting on a green leaf in a sun-dappled jungle in Southeast Asia.

F: Petrognatha gigas – Subfamily Lamiinae. Native to tropical Africa, this species can almost disappear while sitting on charred wood despite its size. Females are attracted to recently burned areas where they deposit eggs in the damaged wood as a host for their larvae.

G: Onychocerus scorpio – Subfamily Lamiinae. This South American species is a great example of cryptic coloration which allows it to blend into its surroundings when sitting on dead wood.

H: Acrocinus longimanus – Subfamily Lamiinae. The spectacularly elongate forelegs of this species make it notable amongst the Cerambycidae. The evolutionary driver for this is unknown, and no behavior involving these long appendages differing from other cerambycids has been observed.

I: Rosalia alpina – Subfamily Cerambycinae. This beautiful blue species is found across the European continent but is restricted to old-growth forests, leading to a decline in numbers. It is protected by law in a number of countries. The closely related Rosalia funebris (L) is found in the western United States, and while not uncommon, is not often observed. Can you find the third species, Rosalia batesi, from Japan, in the drawer?

J: Acanthocinus aedilis – Subfamily Lamiinae. The source of the common name of “long-horned beetle” is obvious in this species. It has one of the longest antennae-to-body length ratios in the Cerambycidae.

K: Leptura quadrifasciata – Subfamily Lepturinae. This common species is an example of the lepturines, the “flower longhorns” – showing a common color pattern mimicking the pattern of bees or wasps. The subfamily contains many species that are diurnal pollen feeders.