by Travis Olds

We each have plenty to be thankful and hopeful for this year, but did you know that our traditional American Thanksgiving feast “with all the fixings,” would not be possible without minerals or the people who mine, process, and manufacture the mineral-related materials found in our kitchens?

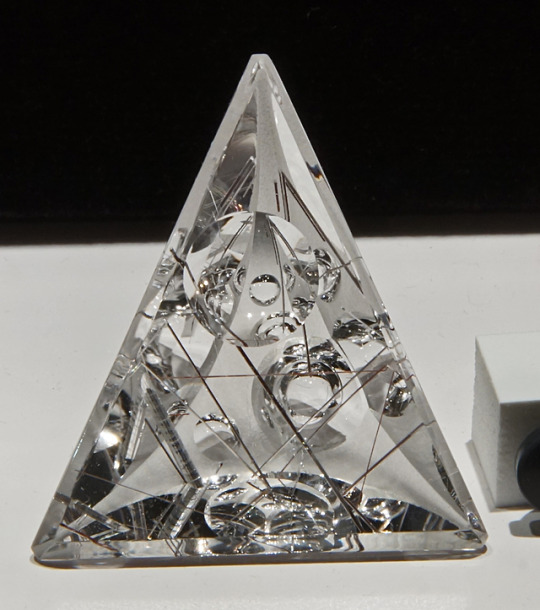

You should thank miners, in part, for the kaolinite clay used to make the fine porcelain china or ceramic plates at your dinner table. When kaolinite is fired in the factory, it partially melts, and crystals of an aluminum-silicate mineral called mullite that hold the ceramic together and give it high heat resistance form on cooling. Also, whether you eat and serve food with silver, steel, or aluminum utensils, extensive work and energy were needed to extract and refine the silver, iron, or aluminum metal necessary for their creation. Silver ore, for example, usually contains many other elements, including lead, zinc, copper, and gold, which can require lengthy chemical or electrochemical processes to separate.

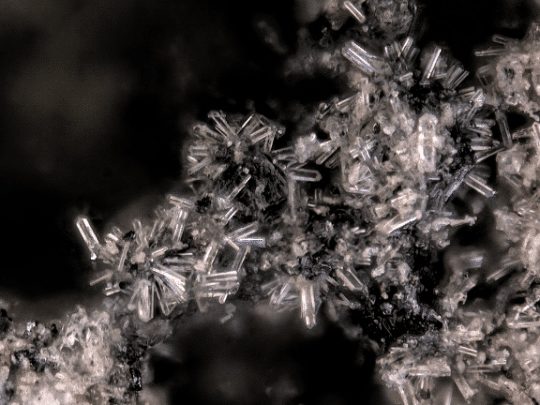

There might also be some unwanted mineral interactions occurring at the dinner table. If your gluttonous Uncle Ned consumes too much salt (sodium) with his gravy and potatoes (high in oxalate) this year, his body may begin to form kidney stones; which are biologically formed minerals made up of crystals of the phosphate mineral struvite and the calcium oxalate mineral whewellite. These biominerals, which can form when your bladder isn’t fully emptied after a sodium or oxalate-rich meal, can be extremely painful, so be sure to drink plenty of water with your meal. Large crystals take time to grow and drinking more water can reduce the concentration of sodium and oxalate in your body, slowing growth of the kidney stones.

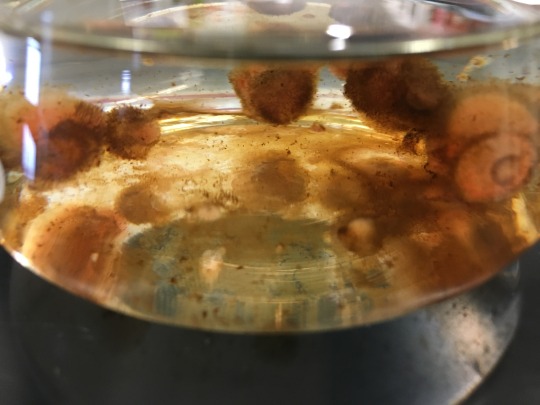

Turkey meat, the mainstay of many Thanksgiving meals, also depends heavily on minerals. Did you know that turkeys actually need to swallow small rocks and pebbles, which are made of minerals, in order to digest their food? “Gastroliths,” or stomach stones, are used by other species of birds, reptiles, amphibians, worms, whales, and even some fish to crush their food and provide more nutrients! Fortunately, we humans have a variety of enzymes and strong stomach acids to break down nutrients in the food we eat.

A surprising amount of nutritional science is applied to raising turkeys; their diet is closely monitored and controlled for proper protein and “mineral” content so that they grow large. You have likely heard the term “mineral” applied to many of our dietary items as well, from mineral water, to a variety of products being fortified with vitamins and minerals, or even the advice that it’s important to maintain a healthy balance of minerals in your diet. The term is somewhat misleading because “minerals” in this sense typically refers to individual atomic elements such as potassium or iron, or to other compounds containing these elements, rather than actual minerals in the strict sense. To a mineralogist like me, minerals are naturally occurring crystalline solids made from a specific combination of elements.

Most often, the elements essential for our diet have been pre-digested, extracted or processed by another plant or animal, or have been chemically separated from a mineral source that makes it easier for our bodies to absorb. For example, most rice and cereal in the U.S. is fortified with B-vitamins and iron with a coating of finely ground nutrient powder. While the source of iron used in the fortifying powder varies, it all originates with the iron-oxide minerals hematite and goethite. Plants, bacteria, or stomach acids break down these minerals into iron cations that are easier for our body to process.

Thanksgiving vegetable dishes deserve special attention because plants can be the best sources for certain nutrients. In many cases, fruits and veggies grown on the farm also need help with their diet. Feldspar minerals present in soil hold on strongly to certain elements like K, more commonly known as potassium, making it hard for plants to extract this element. Farmers address this problem by using fertilizers like manure, containing predigested and readily absorbed phosphorous, nitrogen, and potassium, to produce a bountiful harvest

This year, please extend a bit of thankfulness to minerals, but mostly give thanks and recognition to the people that work hard to make your Thanksgiving possible; be it a miner, factory worker, your grocer, butcher, farmer, doctor, or all those working behind the scenes and on the front lines that keep us happy, healthy, and well fed.

Travis Olds is Assistant Curator of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is biogeochemistry?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Olds, TravisPublication date: November 9, 2020