by Riley Riley

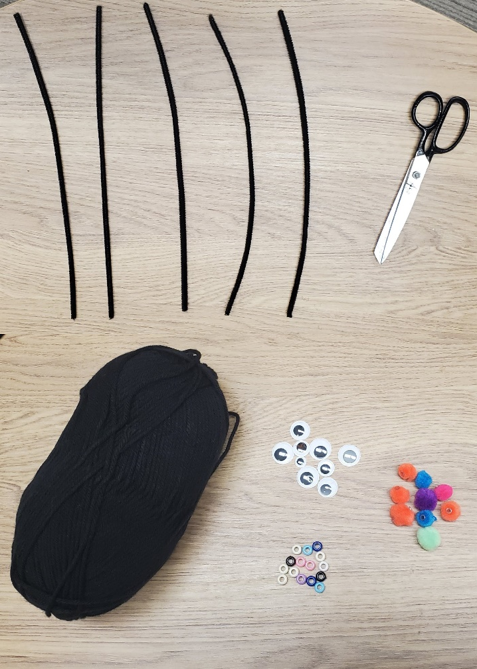

For this simple craft, you will need 5 pipe cleaners, scissors, and any (optional) decorative items to create a spider that you can place or hang around your space. This activity requires a grown-up!

Spiders are an incredibly diverse group of arthropods that come in nearly every color, so don’t be afraid to get creative with the colors and decorations you use for your spider creation!

If you would like to know the names of some colorful and unique spiders, please check the list at the end of this guide to use in your future spider exploration!

Instructions

- Spiders, like all arachnids, have eight legs. So, the first step is to cut four pipe cleaners in half to make eight pieces that will be used as your spider’s legs.

- We will use the remaining full pipe cleaner to create the spider’s body. First form a circle with the pipe cleaner and twist the ends together so that the circle remains closed.

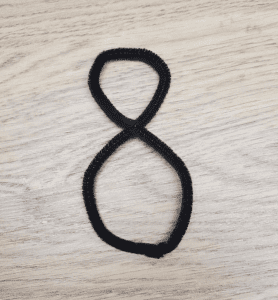

- Spiders have two body segments, the abdomen and the cephalothorax. To create these two segments, pinch and twist the circle so that it forms a figure eight.

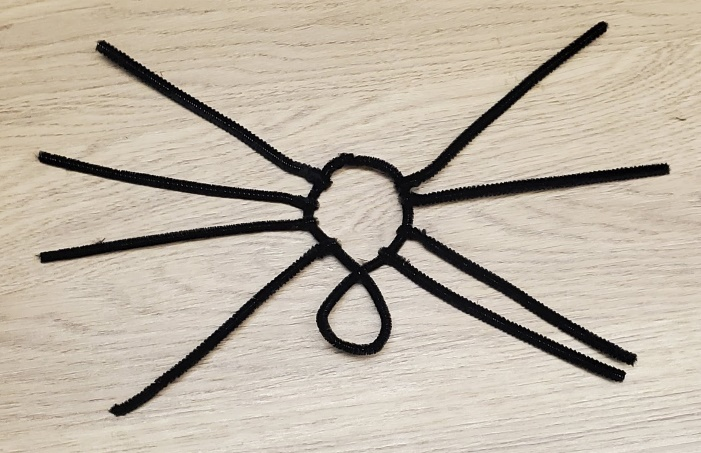

- Now it is time to attach the legs of your spider! All eight of a spider’s legs are attached to its cephalothorax, so choose one side of your figure eight to designate as the cephalothorax and begin attaching the legs. To do this, take one of the leg pieces and hook it around the side of the body. Twist the end of the leg piece to secure it to the body. Repeat this step seven more times until you have four legs on each side of the body.

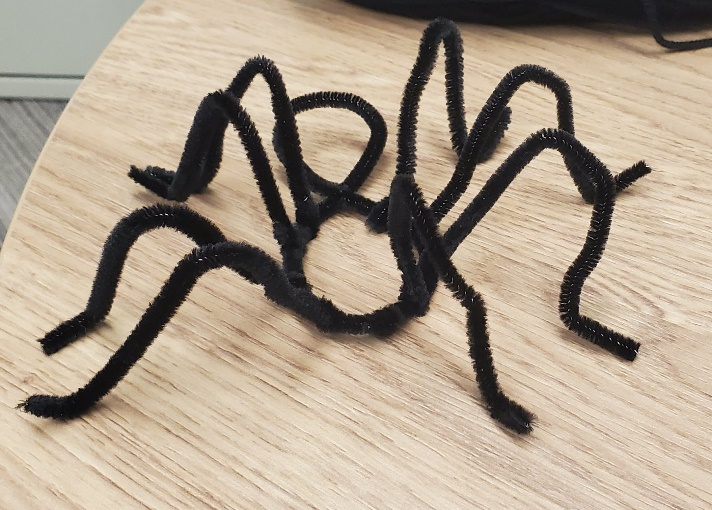

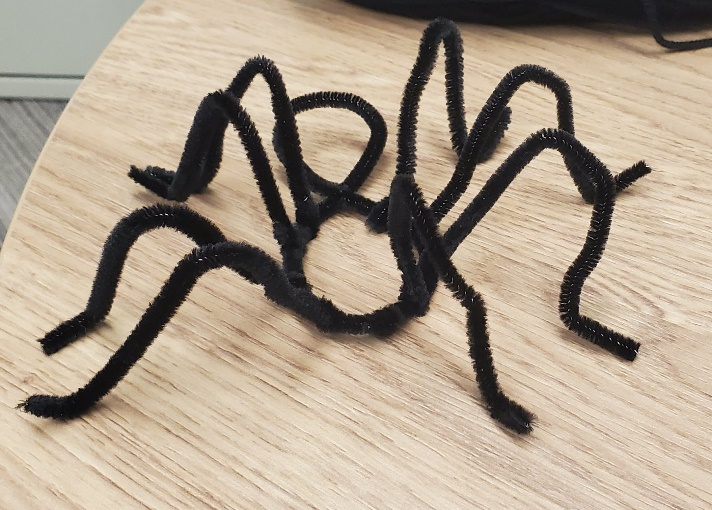

- At this stage, your spider is finished being constructed! You can leave your spider like this or you can bend the legs to create more of a 3-dimensional creature. This is when you can add any embellishments like pompoms, beads, or eyes to your spider as well.

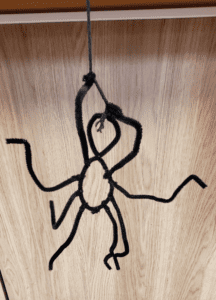

If you would like to hang up your spider, you can represent its spinnerets – the silk producing organs – by tying a piece of string or yarn to the end of the abdomen (the body segment without the legs).

The Spider Rainbow

Red – Dominican Spider (Alcimosphenus licinus)

Orange – Shamrock Orb-weaver (Araneus trifolium)

Yellow – White-banded Crab Spider (Misumenoides formosipes)

Green – Green Huntsman Spider (Micrommata virescens)

Blue – Singapore Blue Tarantula (Lampropelma violaceopes)

Purple – Ecuadorian Purple Tarantula (Avicularia purpurea)

Pink – Pink Crab Spider (Thomisus onustus)

Newton, B., & Bessin, R. (2009, November 19). Spider Anatomy. Kentucky Critter Files – University of Kentucky Department of Entomology. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://www.uky.edu/Ag/CritterFiles/casefile/spiders/anatomy/spideranatomy.htm.

World Spider Catalog (2021). World Spider Catalog. Version 22.5. Natural History Museum Bern, Retrieved September 30, 2021, from http://wsc.nmbe.ch doi: 10.24436/2

Riley Riley is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.