by Mason Heberling

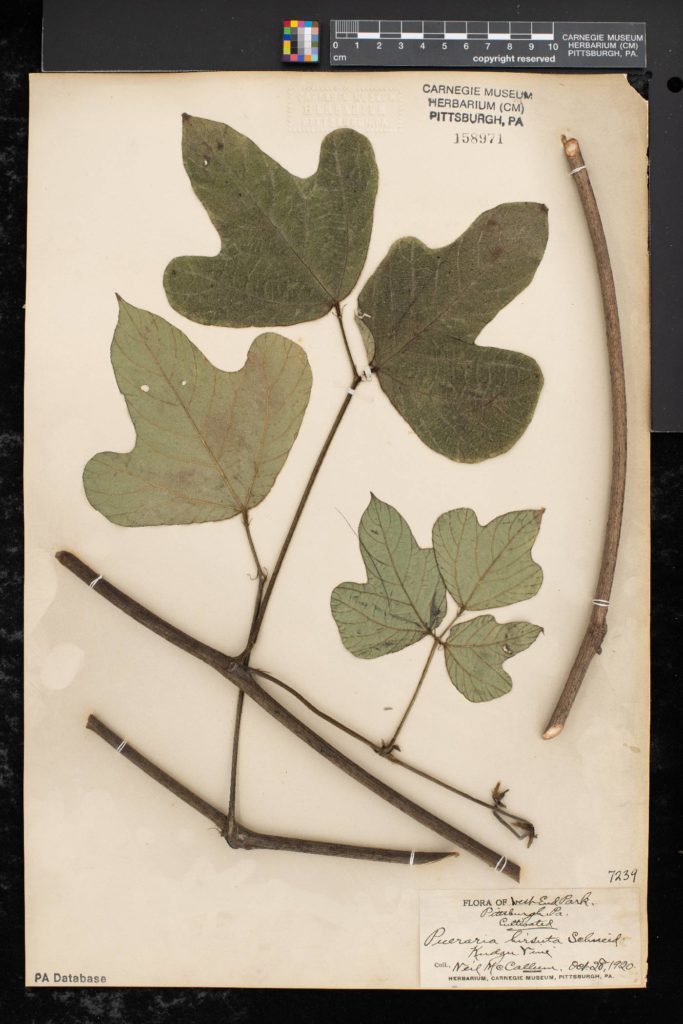

This specimen of Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata) was collected on October 28, 1920 by Neil McCallum at West End Park, Pittsburgh. The plant was collected in cultivation, meaning it was intentionally planted and grown in a garden or similar managed landscape. This specimen is one of the earliest records of the species in Pittsburgh. (It was also collected two years before).

Kudzu is a vine in the bean family, Fabaceae, with beautiful purple flowers. Native to East Asia, it was introduced as an ornamental plant to the United States from Japan in 1876 at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It was promoted in the 1930-40s in the southern US to prevent soil erosion. However, it is now an invasive species, with big ecological impacts. It is widely known as “the vine that ate the South.” A quick Google search will show you striking pictures of the vine covering large areas of land, covering trees, shrubs, logs, and anything else in the path of its explosive growth. Kudzu shades out existing vegetation and can drastically alter the ecosystem.

It is not common in Pennsylvania, but perhaps might become so. Kudzu is listed by the state as a “Class A Noxious Weed” – meaning it is assessed as a high invasive risk and ecological/economical concern, but is uncommon and possible to be eradicated. It cannot be sold or planted commercially in Pennsylvania.

It is currently most invasive in the South, but a study published in 2009 by Dr. Bethany Bradley and others suggests that the species may become more invasive in the north (including Pennsylvania) as climate change continues.

You can find this specimen online here, and search our collection at midatlanticherbaria.org.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Collected on this Day in 1951: Bittersweet

Collected on this Day in 1930: Native…or Not?

Collected on this Day in 1995: Ragweed

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heberling, MasonPublication date: October 28, 2022