by Koa Reitz

Reposted from Plant Love Stories.

One of my earliest memories as a child is my friend finding a big leaf when we were at the park, and me bursting into tears because I wasn’t the one who found it. Fall was my favorite season because as I walked around, there were plenty of things for me to pick up! I was absolutely captivated by the leaves that fell off of the trees, and would pick up as many as I could. I don’t remember why I was so attached to these leaves–the dead part of the plants around me–but I would always end up with a stack of leaves when I got home.

I think a big part of my obsession with collecting leaves was their colors. But sometimes I would find a particularly big leaf and, as a small child, I was absolutely dumbfounded at the leaf bigger than my head. I had to have them. When I brought the leaves home however, I never kept them, they would sit outside for a while until they would eventually blow away or decompose in the yard. This wasn’t exactly an issue for my young self, as object permanence had yet to fully develop. And there were always more leaves to find!

As I grew up, I became less and less invested in picking up all of the leaves I saw. I think eventually I saw so many that it was hard to find a new color combination I had yet to see, so leaf searching had lost its allure. I would still stop to look at the leaves when there was a particularly vibrant red, or an exciting combination of green, yellow, and orange all in the same leaf, but I left the leaf where it stood. No more collecting for me.

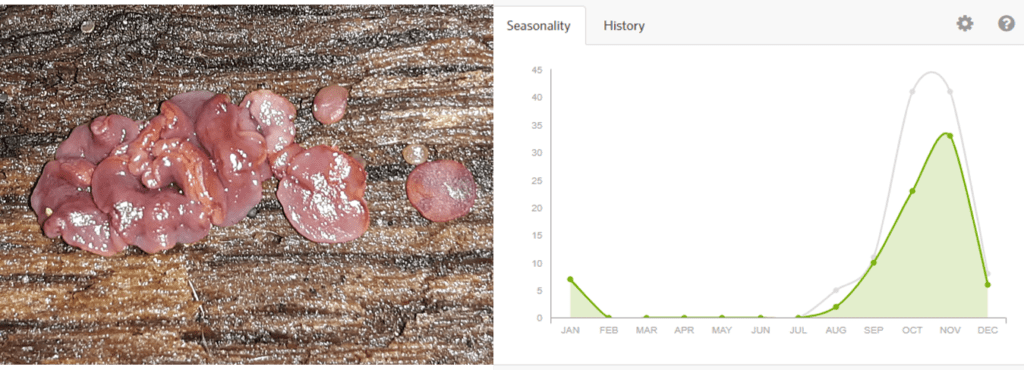

Until recently, I had no reason to think that collecting plants could have any purpose, scientific or otherwise. Contrary to my thinking, there is a vast and important process of collecting and storing plants, of all kinds, to be used for reference and scientific research. Herbaria are collections of preserved plants dating as far back as hundreds of years ago. These specimens can be used for a variety of things including taxonomic classifications (scientific naming systems), DNA sequencing, and phenological observations. Phenology is the study of the time when certain things in the life cycle of a plant happen. For example, phenology can look at the time in a flowering plant’s life that it begins growing new leaves, when it grows flowers, when it develops its fruit, or when leaves turn colors in the Fall. Phenological data from herbaria have been used to look into the past in ways that wouldn’t be possible without a collection of old, dead, plants. A group of scientists at Boston University used herbarium specimens to determine that a warmer climate led to earlier flowering times. This conclusion has various implications including evidence that a warming planet has concrete impacts on the natural environment and changes how we look at climate science overall. It is important to look to the past if we’re going to make informed decisions about the future, and herbaria are full of accessible and valuable information that can help develop scientific claims of all different kinds.

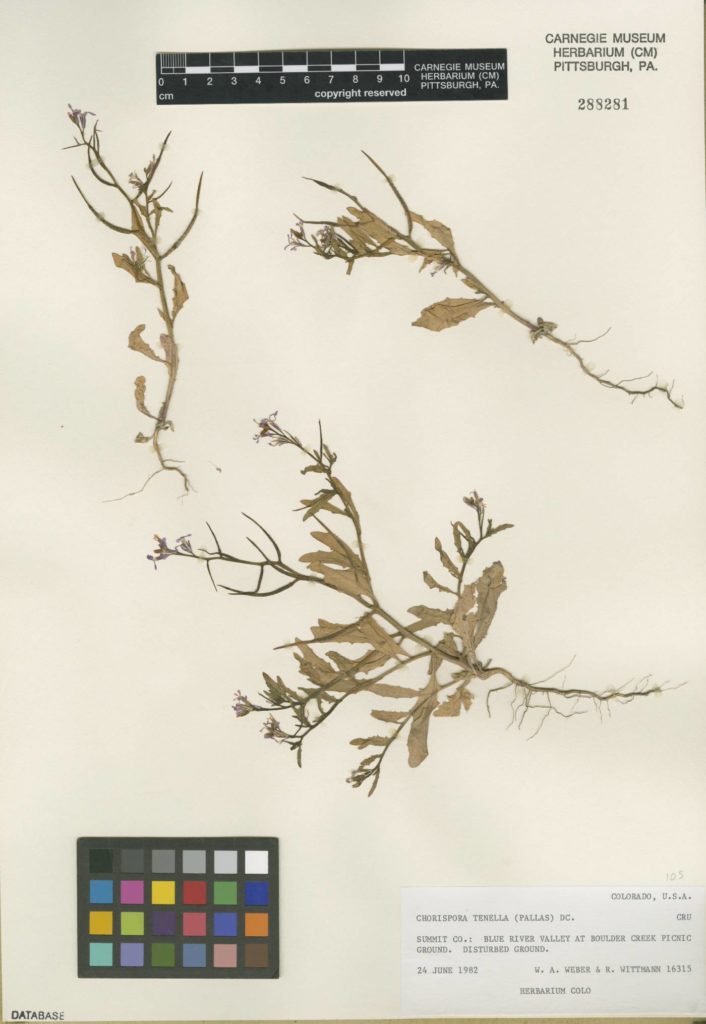

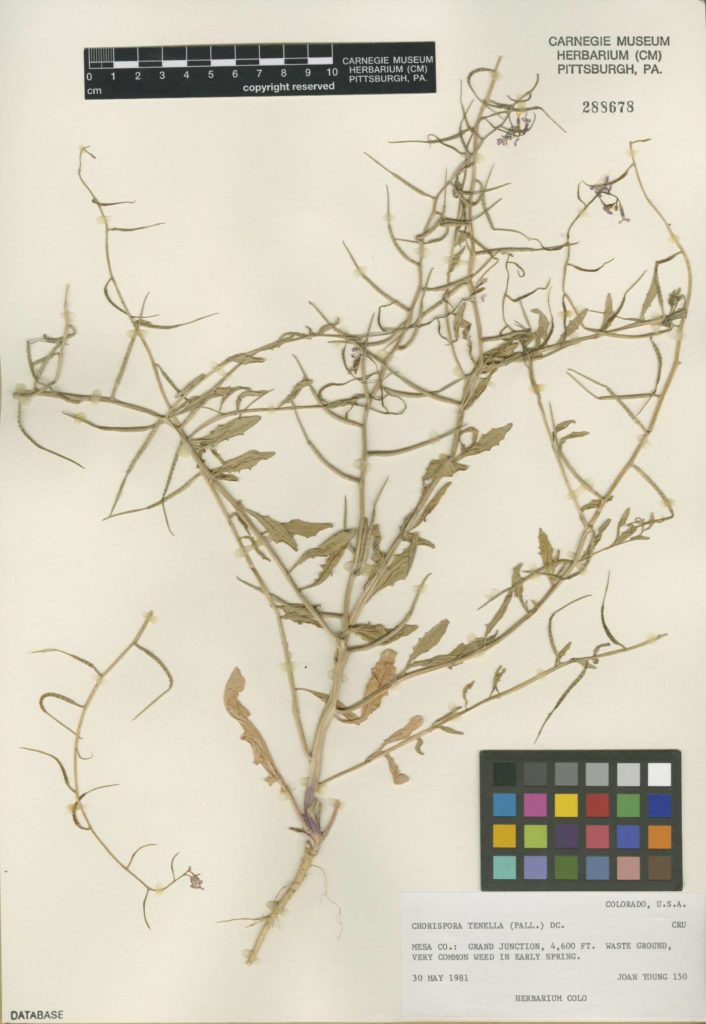

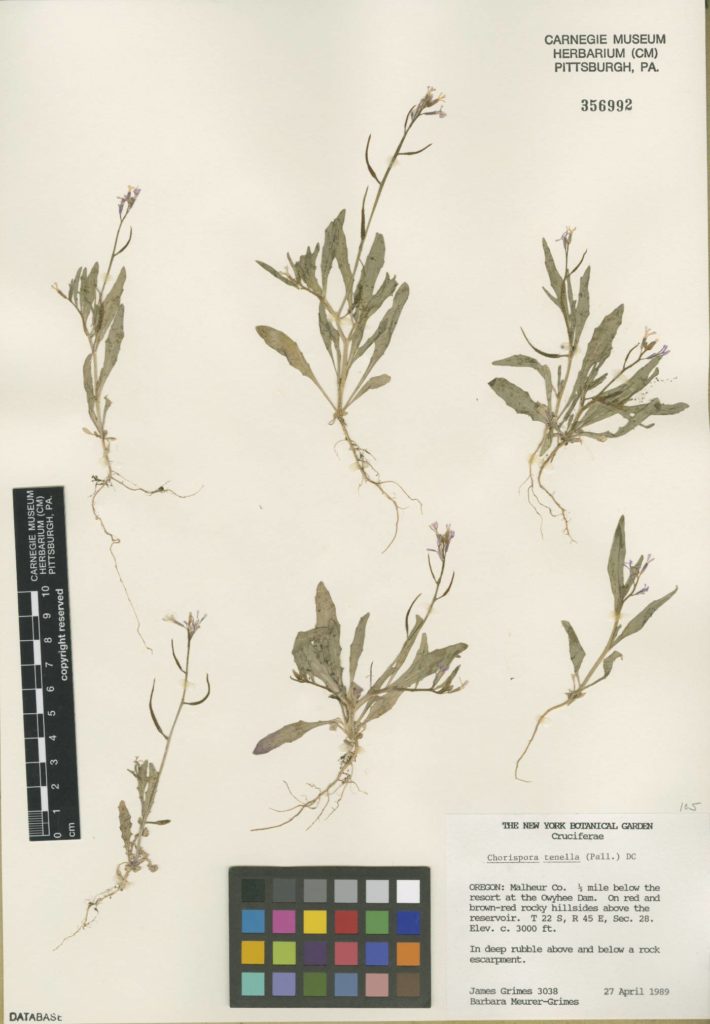

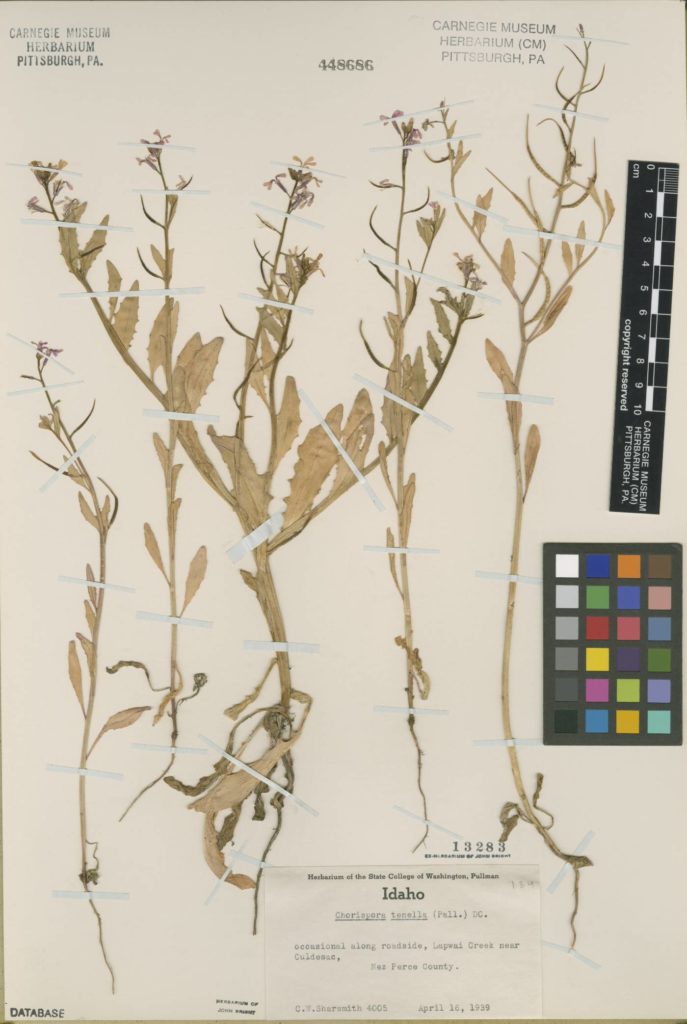

I am particularly interested in Herbaria because of my work in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Herbarium. It was compelling to me to work with scads of cabinets full of dead plant specimens. Currently, I am working on a project where I look at digitized Chorispora tenella (purple mustard) specimens in the Carnegie Museum Herbarium, and herbaria from all over the US. Chorispora tenella is a plant that is invasive in parts of the Western US, and we are looking to see how the phenology has changed over the course of its invasion. There are endless questions about the timing of flowering or the spatial differences in flower or fruit number, just to name a few. I think I started to form a relationship with the plants, as I look at image after image and count the number of flower buds, flowers, and fruits, just as I had formed a relationship with the fallen leaves when I was young.

There’s so much to learn from these seemingly simple and still specimens. When I do this work, it brings me back to when I was a child and had the (not so permanent) leaf collections of my own. I think there was a part of me as a child that wished to observe what I gathered further, but I had no method or resources to preserve my collections. Now, with herbaria, there’s access to thousands of species of plants that span all over the world. They open up countless lines of study and things to learn and explore, all from dead plants in cabinets. I even find myself collecting and questioning things again, renewing my sense of exploration. And I still make time to find leaves bigger than my head.

Koa Reitz is an undergraduate student studying Ecology and Evolution at the University of Pittsburgh, and a research intern at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees, interns, and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

** To learn more about these natural history specimens, you can visit the Mid-Atlantic Herbaria Consortium. Specimens are as follows (left to right): CM356992 collected in 1989 in Oregon; CM448686 collected in 1939 in Idaho; CM288678 collected in 1981 in Colorado; and CM288281 collected in 1982 in Colorado.

Related Content

Collected On This Day in 1951: Bittersweet

Collected On This Day in 1934: European larch

Sharing Shipping Space with Amphibians and Reptiles

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Reitz, KoaPublication date: March 25, 2022