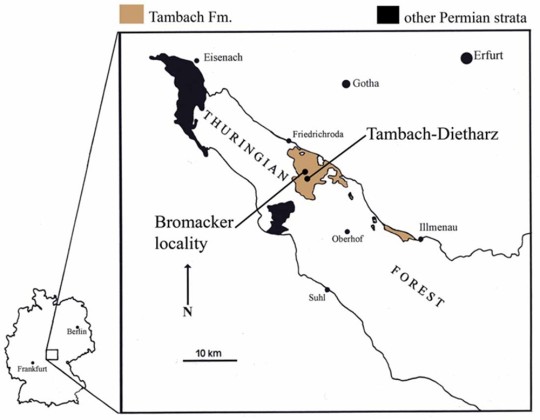

Paleontologist Thomas Martens has an amazing ability to find fossils. After he discovered the first vertebrate fossils at the Bromacker site in an abandoned commercial quarry in 1974, he and his father Max found additional fossils in the bottom of a deep pit they’d dug with hand tools, an excavation that Dave Berman, Stuart Sumida, and I fondly dubbed the “elevator shaft.” Years later, Thomas used funding from the German federal government to drill rock cores in the field surrounding the Bromacker quarry to help understand the geology of the fossil deposit. Amazingly, at one of the spots Thomas had selected, the drill core penetrated a skeleton of Diadectes absitus. So, it wasn’t surprising that in 2008 Thomas found a skull and partial skeleton of D. absitus and a small skull of a fossil animal new to science at a construction site for a new store in the nearby village of Tambach-Dietharz.

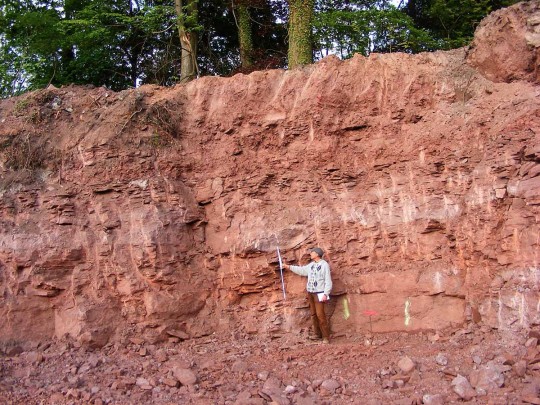

It makes sense, however, that vertebrate fossils were found close to the Bromacker quarry. Fossils from the Bromacker were preserved in the Tambach Formation, a 200–400-foot-thick unit of sediments that were deposited in the small intermontane Tambach Basin about 290—283 million years ago during the Early Permian Epoch. The Tambach Basin covered an area of about 155 square miles and was internally drained; that is, there were no rivers or streams flowing into and out of the basin. During periods of extremely heavy rain, water and mud would flow down the basin sides in what are called sheet floods and pool in the basin center, which is where the present day Bromacker quarry and Tambach-Dietharz are thought to be located. Any animals killed during these events would be carried by the sheet floods to the basin center where they’d have been quickly and deeply buried in mud settling out of the ponded water and later become fossilized. It is assumed that animals captured by the sheet flood events inhabited the Tambach Basin, because carcasses couldn’t have been carried into the basin by rivers and streams.

While preparing Bromacker fossils, I’d typically read literature related to the fossil I was working on, write notes on what I thought were important features in the fossil, and give my notes to the person leading the project. When Dave was the lead, we’d typically have lots of discussion about certain features preserved in the animal, conversations that often directed the course of preparation. This time, in addition to preparing the new find, I was designated as the lead author for the publication that would name and describe it.

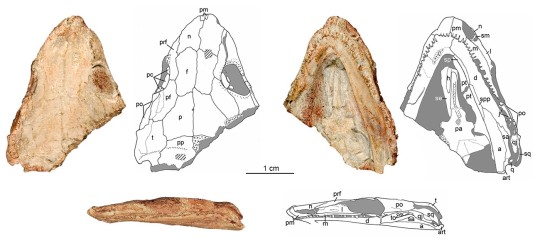

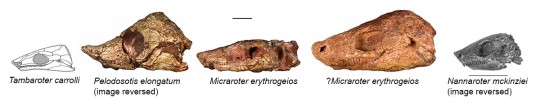

Tambaroter is a member of the Microsauria, a diverse group of small amphibians that were once thought to be reptiles, a hypothesis that some paleontologists are currently revisiting. Microsaurs inhabited a variety of habitats and exhibited a range of body forms. Some were highly terrestrial with limb proportions similar to those of lizards, whereas others were aquatic and had elongated bodies and reduced girdles and limbs. Still others were adapted for burrowing or rooting through leaf litter. Tambaroter belongs to this latter-most group, which is named Recumbirostra for their recurved snout, in which the front of the mouth is overhung by the snout.

Tambaroter is member of the recumbirostran subgroup Ostodolepidae. I coined the name Tambaroter, which is derived from “Tamb,” for the Tambach Formation, and the Greek “aroter,” meaning plowman, in reference to the snout shape. Two previously named ostodolepids, Micraroter and Nannaroter, have the “aroter, suffix in their name, so usage of the “aroter” suffix was a continuation of this. The species name, carrolli, honors microsaur expert Robert Carroll (then Curator Emeritus at the Redpath Museum, McGill University, Montreal, Canada).

When Tambaroter was published on in 2011, it was the first ostodolepid to be found outside of the USA (the others are from Oklahoma and Texas) and is the oldest one known. Other, possible ostodolepids have since been described from the American Midwest and Germany. All ostodolepids have a wedge-shaped skull and recumbent snout, which is accentuated in Pelodosotis. Based on these features, scientists think that ostodolepids burrowed or searched for worms and other prey in leaf litter. Remarkably, the skull of the tiny Nannaroter is so strongly built that it could have withstood burrowing headfirst into the ground by using its shovel-like snout to loosen dirt and its broad, flat head to push soil against the burrow ceiling. Because the sutures between individual skull bones in the Tambaroter type specimen are not tightly fused together, we think it belonged to a juvenile, so we don’t know if the adult skull would’ve been as strongly built as that of Nannaroter.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature one of the Bromacker’s top carnivores. To learn more about Tambaroter, read the publication that described the animal here.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Keep Reading

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part XI: Dimetrodon teutonis, an apex predator