Carnegie Museum of Natural History has a large and expansive collection of artifacts, oddities, and wonders. It also has its fair share of mounted animals and skeletons on display, which makes it an ideal spot for the wandering artist. Where else can an artist study both extinct and extant species up close and in great detail? If, like me, you’re an illustrator who loves to draw animals, you could, for example, grab your sketchbook and head to the museum’s Bird Hall to get a close look at the flightless dodo (Raphus cucullatus). Driven to extinction by European colonists during the 1600s, early artists’ renderings provide some of the best evidence for the dodo’s appearance in life. Perhaps surprisingly, this bird is now known to be closely related to pigeons!

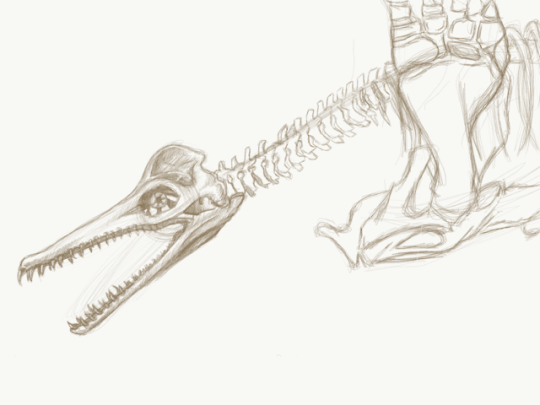

If your tastes are more prehistoric, check out the museum’s sprawling Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Travel back in time to ancient seas and imagine the graceful movements of the plesiosaur Dolichorhynchops bonneri while the giant carnivorous mosasaur Tylosaurus proriger hovers ominously above you. These marine reptile groups vanished in the mass extinction that also wiped out non-avian dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago.

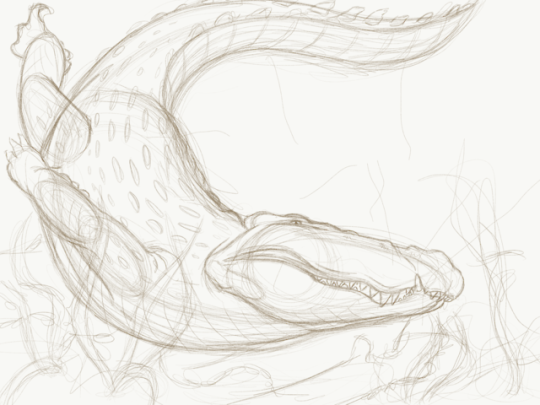

Or perhaps you’re more interested in observing and sketching modern day animals? If so, visit the Hall of North American Wildlife and Hall of African Wildlife on the museum’s second floor. Get up close and personal with the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) trio and capture their anatomy in detail. It’s the safest way to do so – not to mention the only way to do so here in Western Pennsylvania! (Reports of alligators in our rivers notwithstanding.)

So, my fellow artists and nature lovers, as I hope this post has shown, there are scores of species to inspire you here at the museum. Grab your sketchbook and come on over!

Hannah Smith is an intern working with Scientific Illustrator Andrew McAfee in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees, interns, and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Celebrating Women in the Natural History Art Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Smith, HannahPublication date: August 12, 2019